The Doomscroll Sublime

PreCursor Monthly – February 2021

We are now beyond the time of Johnny Mnemonic, which was set in January 2021, and it is worth reflecting on the distinction between material limitations and human ones.

Johnny is a mnemonic courier, a cyborg who smuggles information in his head. For data too sensitive to send over the Internet, a courier can get it from Point A to Point B. Originally a William Gibson story in 1981, Johnny is an image of how the rise of personal computers might extend the intrusion of business activity into daily life.

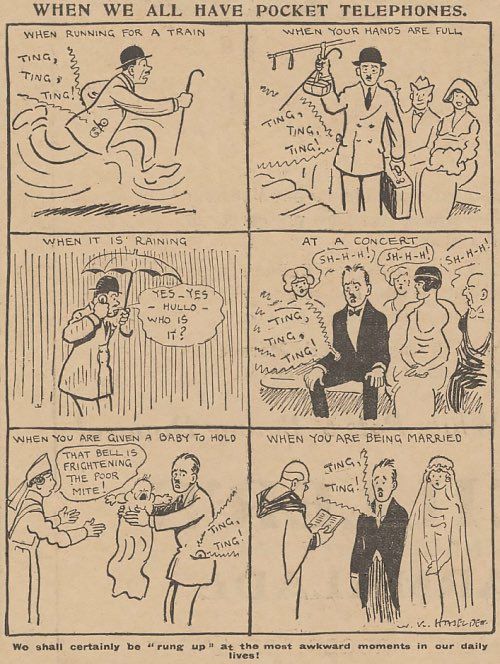

You can see the dynamic reflected in this 1919 cartoon. Haselden anticipates mobile phones, yes, but in a context of urban growth in which home telephones were still relatively new. Such technology provided many positive uses, but also expanded one's sense of availability. Still, the phone only connected to the home – but what would happen when this expanded into other spaces, and then followed one everywhere? The subject is not the average person in each panel; he is a busy man, with a harried commute, in particular demand.

Just as the man in the 1919 comic is being cut off from important moments, Johnny's personal memories are being written over by corporate data. This is a technical limitation – storage space runs out – but Gibson conflates the technical and the personal.

Gibson conflates the two again a decade later in Agrippa (A Book of the Dead), but pressing up against our human limitations offers something different: the experience of the sublime.

Internet – 2021

The film adaptation of Johnny Mnemonic expands the story with a pandemic plot and added hurdles such as a shepherd-staff-wielding street preacher. Gibson's story is much more narrowly focused: Johnny was tricked into stealing from the Yakuza and needs to complete the job safely.

Written very early in the history of what would become known as cyberpunk, the story starts with a great depiction of the high-stakes push-and-pull of high tech and low life:

I put the shotgun in an Adidas bag and padded it out with four pairs of tennis socks, not my style at all, but that was what I was aiming for: If they think you're crude, go technical; if they think you're technical, go crude. I'm a very technical boy. So I decided to get as crude as possible. These days, though, you have to be pretty technical before you can even aspire to crudeness.

A simple version of this story might lean into the unfaltering superiority of combining technical with street knowledge. What needs to be further demonstrated, however, is the outsized advantage of technical superiority. A "neural disruptor" removes Johnny's ability to control his hand. He has this all set up, all lined up perfect, but he can't pull the trigger. His high-tech savior, Molly Millions (later seen centrally in Neuromancer), only brings him deeper into that technical world.

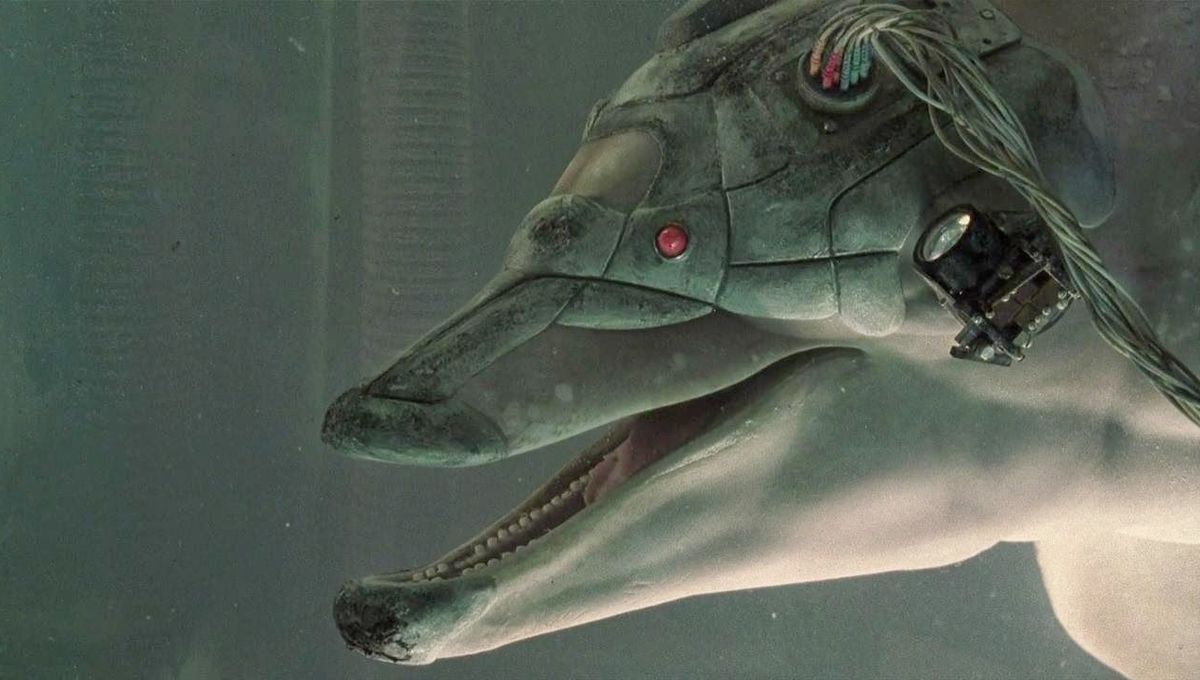

Just like how Johnny serves his role, Jones the dolphin was military tech. After being abandoned, Jones' cybernetic enhancements are repurposed. With the help of Jones, Johnny is able to retrieve the data which had been encrypted and lost in his head.

In Gibson's screenplay for the 1995 film, this retrieval becomes more personal. To make room for corporate data, Johnny dumped some of his long-term memory: his childhood. How is it, though, that the cybernetic dolphin can bring back memories meant to be gone forever?

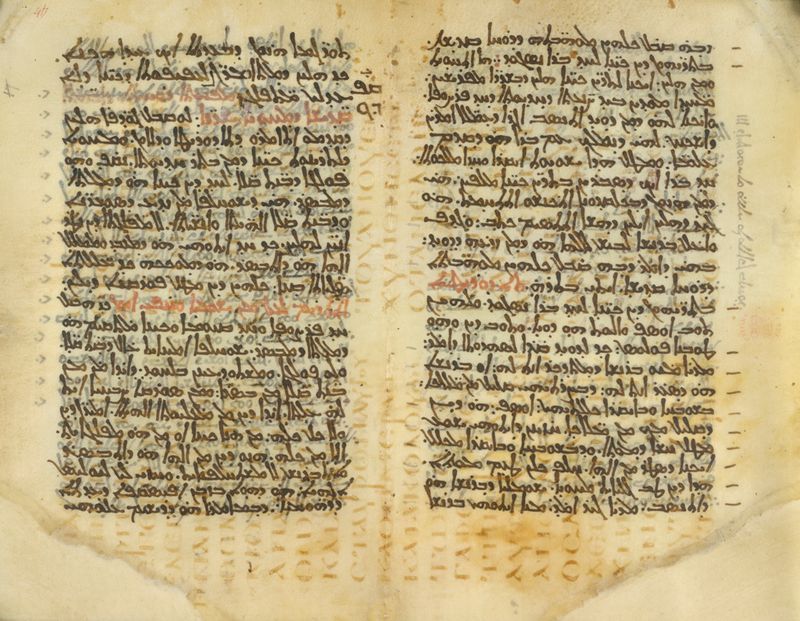

Such recovery on computers was first conceived on paper through the palimpsest, a process of washing away text to reuse the writing surface. This process went back to the 6th century, but in the 19th, scholars found chemical means of resurfacing the earlier text.

In 1845, Thomas De Quincey picks up on this in Suspiria de Profundis. As he explains, such processes of recovery are valuable because something which may seem nonsense to one generation – and so erased – may revive into sense for a succeeding generation. Having explained this whole history for several pages, he now asks, "What else than a natural and mighty palimpsest is the human brain?"

As with the textual artifact, our memories may be obscured to our conscious mind, but all may be recovered through similar acts of chemistry.

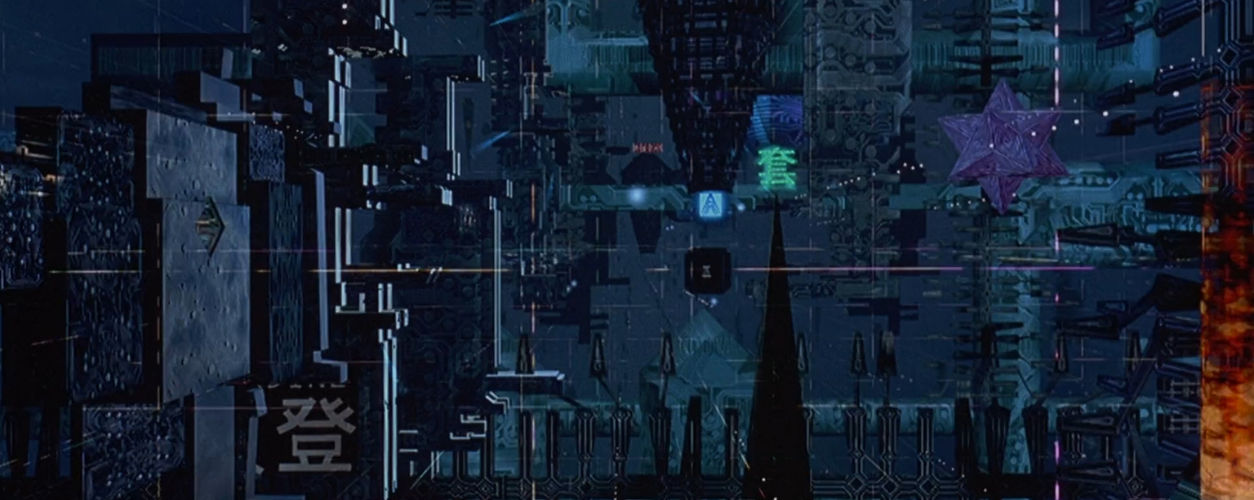

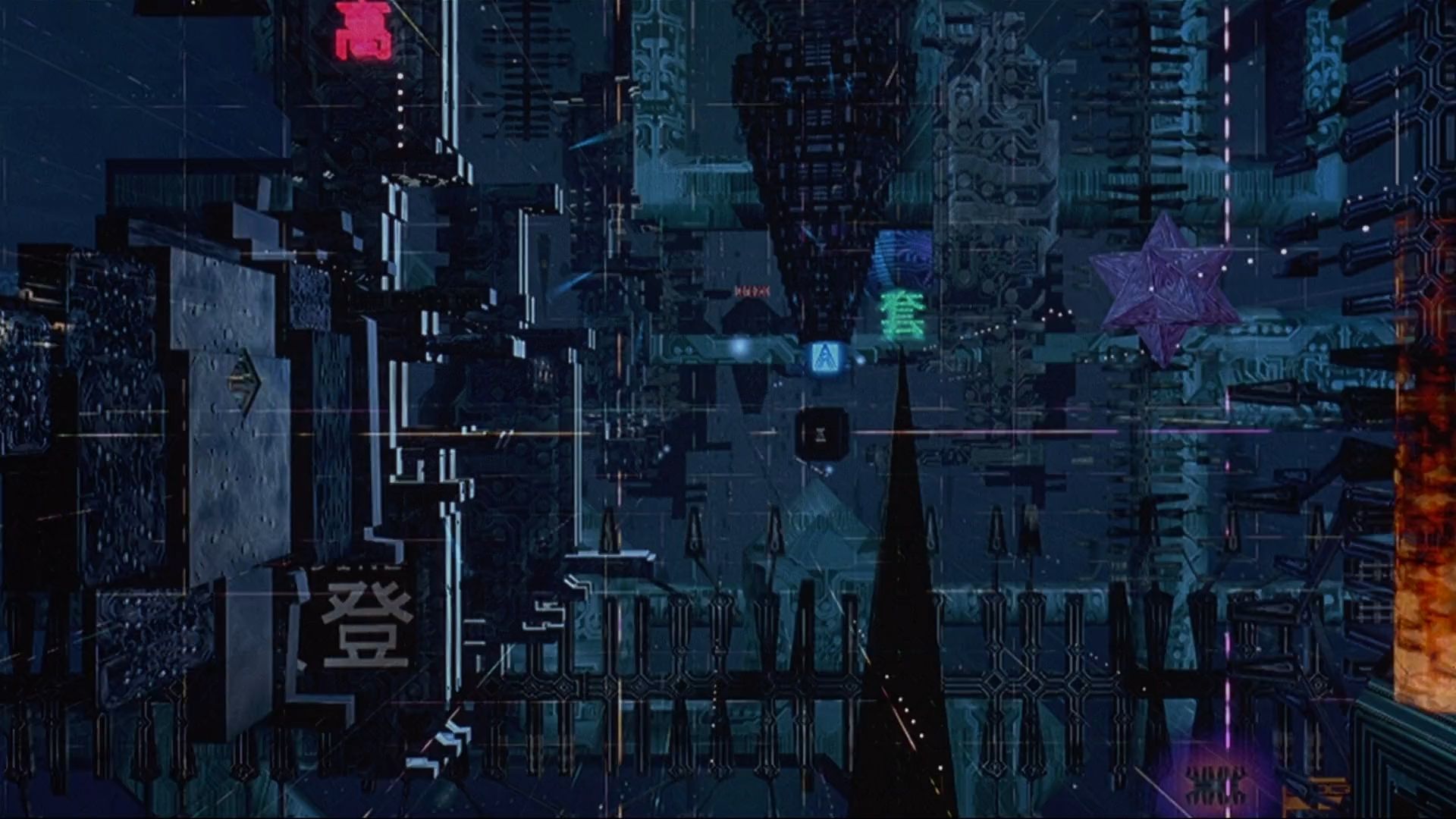

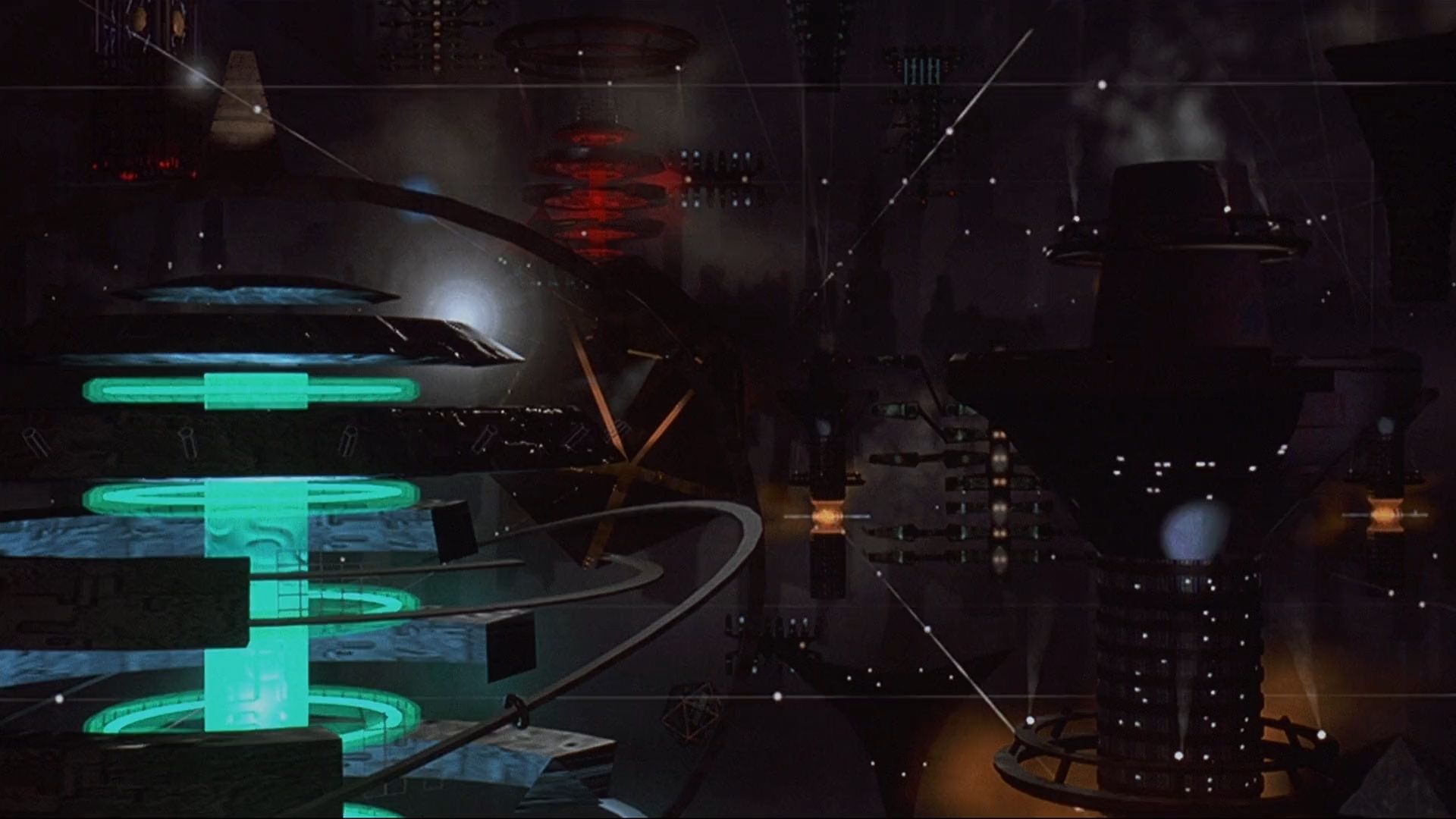

Depictions of cyberspace in Johnny Mnemonic (1995)

Alongside the more sentimental interest in getting back to his personal memories, it also seems necessary that Johnny have this recognizable foundation stored somewhere. He is, as he says, "a very technical boy." Beyond his niche role as a mnemonic courier, cyberspace as well is presented as a chaotic adventure of navigating a vast sprawl of indecipherable 3D objects.

Overloaded With Despair

The act of navigating an overwhelming quantity of virtual content is widely familiar in the actual Internet of 2021. One type of navigation is known as "doomscrolling," in which one is displeased in browsing negative content, but cannot stop scrolling.

Such online navigation may seem a parallel to reading through some types of literature. This is the implicit claim in the recent Issue #2 of Neutral Spaces, titled "Doomscrolling."

Bringing together 94 writers, some of which have multiple short pieces in the online magazine issue, attempting to complete a reading can be exhausting. Like with scrolling a social media feed, the fact of constantly switching back-and-forth through different genres, topics, and styles furthers the exhaustion. A long session of reading a typical novel can be immersive; reading such assorted content as collected in the magazine requires constant readjustment.

The selection tends toward despair. Even a jokey poem such as Mike Topp's "Little Known Facts About People" mixes fact and fiction, light-hearted trivia and information with some serious weight within American politics. Other works tackle death, illness, doubt, etc. Derick Dupre writes in "Spirally Arranged, Mostly Broad, and Heart-Shaped":

The gloom of smog had mollified my fear of something balmy. No one ever came to my mambo recitals.

Reading through various levels of despair text after text across 94 writers is brutal. Reading these expressions as a collection of literature, however, we are getting a vast selection of distinct visions. These visions are mainly of less pleasant elements of life, which is not to say they are not worth considering.

Seeing this quantity of writing is inherently a bit sublime. Not only can it be a bit unpleasant to try to take it all in, but we are actually incapable of understanding it all at once. The sublime is also itself displeasing. As described by Immanuel Kant:

The feeling of the sublime is, therefore, at once a feeling of displeasure, arising from the inadequacy of the imagination ... In the immeasurableness of nature and the incompetence of our faculty for adopting a standard proportionate to the aesthetic estimation of the magnitude of its realm, we found our own limitation.

What is notable with doomscrolling – whether through social media feeds or this literary magazine – is that it is not a material limitation. Film-Johnny has finite storage space; we feel as though the feed can keep scrolling forever. The real limitation is human:

Eventually, we are exhausted, and must cease scrolling.

Scrolling Memory

If all is forever etched on the palimpsest of the human brain, however, then all of the doomscrolled content ends up somewhere in our memories.

Between the story of "Johnny Mnemonic" in 1981 and its film adaptation in 1995, William Gibson writes a rare poem. Published in 1992, Agrippa (A Book of the Dead) is a reflection on memory and photography. It was also designed to only be read once.

The book was released with two versions. A physical book used a chemical process to make the text fade rapidly when exposed to light. A digital copy, distributed on a floppy disk, runs a program which scrolls through the text. Upon completion of the poem, the program encrypts itself, preventing further reading of the text.

Like the moments in earlier life, experienced once but recorded as memory, we also experience the text of Agrippa once and then must rely on our memory to return to parts of it.

The content of the poem is completely removed from the cyberpunk style typical of Gibson's writing:

Now in high-ceiling bedrooms,

unoccupied, unvisited,

in the bottom drawers of veneered bureaus

in cool chemical darkness curl commemorative

montages of the country's World War dead,

just as I myself discovered

one other summer in an attic trunk,

and beneath that every boy's best treasure

of tarnished actual ammunition

real little bits of war

but also

the mechanism

itself.

The image is technical, in the way that Johnny is technical in figuring out to modify the shotgun shells, research via microfiche, and build a lever-action press. Seeing it scroll through and then encrypt on a screen, however, we are forced to grapple with our technological memory extensions.

Gibson forces an especially strict material limitation, but all these media – photographs, printed works, computer programs – are ultimately fragile. As we see the rise of the personal computer around this time, the importance of human memory is not diminishing. Johnny is very technical, but as imagined by Gibson, such storage can only be placed on top of our normal memory, not expand it.

As doomed images scroll before us, we are brought to a state of sublimity. Returning to Kant:

The mind feels itself set in motion in the representation of the sublime in nature; whereas in the aesthetic judgement upon what is beautiful therein it is in restful contemplation.

Escapist media can often put us at rest, but doomscrolling sets the mind in motion. As with Johnny Mnemonic's corporate work, it can also be a moment of intrusion of the stressful, professional world into one's daily life. Unlike the discrete incident of a single phone ring, however, what is most striking here is the impositon of the seemingly infinite.

Our imaginative faculties fail us, so we are determined to keep scrolling. As we become fully immersed in the doomscroll sublime, we move past the initial displeasure to discover deeper potential to conceptually navigate such expanse.

Around the Web

"The Big Sleep": Max Anton Brewer discusses politics and magic as interfaces, and explores image generation as a system for accessing a collective imagination, a developing possibility which comes with serious responsibility.

"Beyond the Screen": Emina Melonic explores the weird, new human dynamics of social media, especially Facebook. Particularly interesting is her point about how, amid potentially heated online conversations, people can just leave – suddenly, without comment, and without even really thinking about this departure.

"Antilibrary Book Show and Tell": Brendan Schlagel will be hosting a free event on Saturday, February 13th for people interested in sharing books which you own but have not read, works which thus far merely occupy a vague imaginative space in your mind.

This post was sent first via email as my free monthly newsletter. Each month, I look at least one work of new literature, classic literature, and electronic literature – bringing the three together in conversation. If you would like to receive similar content each month, just add your email address below and then click the confirmation sent to you: