How to Throw Away Lyrical Ballads, After You Have Read It

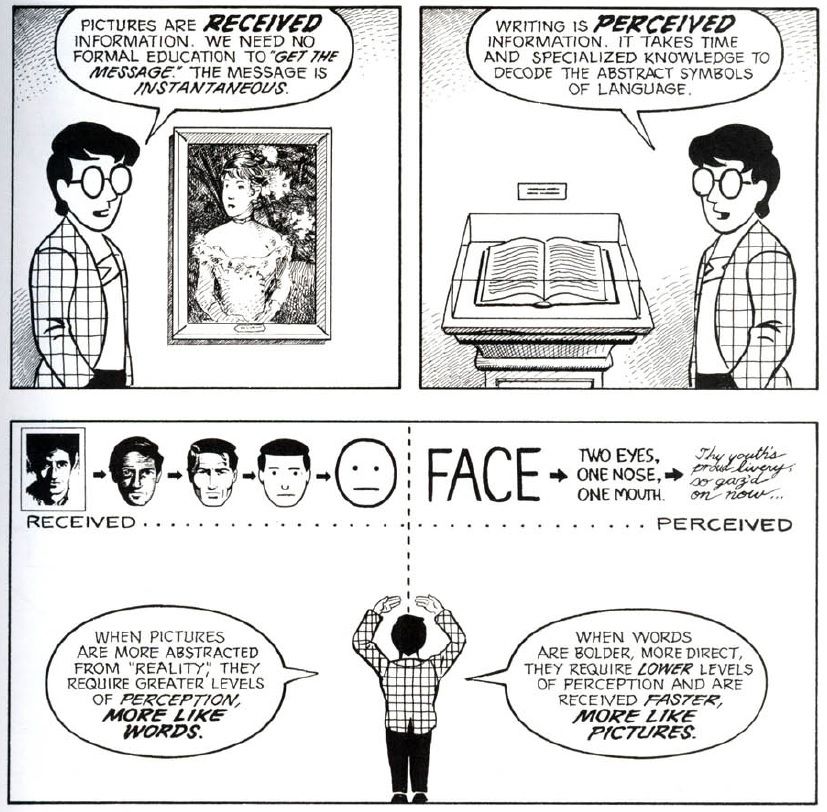

You're walking along and notice a straggling heap of unhewn stones. The story of those stones is known locally, and your personal encounter comes in from outside of that communal knowledge. Blurring those two perspectives together, you have a lyrical ballad.

In "Michael"—the concluding poem in William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's two-volume 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads—Wordsworth writes of this sight:

And to that place a story appertains,

Which, though it be ungarnish'd with events,

Is not unfit, I deem, for the fire-side,

Or for the summer shade.

This humble under-selling of the story he is about to relate is part of a dramatic strategy in which he hopes to deflate your expectation that some grand meaning will be handed down to you—from the speaker of a lyric poem—and that you will instead find your own connection with this image, as he did. A reader of the collection may recall Wordsworth doing the same thing in a poem in Volume I.

"Simon Lee, The Old Huntsman, With an incident in which he was concerned" promises only a simple incident. The opening of the poem is very ballad-like, relating the local legend of the man, and the different claims people make of him and his past feats. The context for these recollections, we later find, is that the speaker encountered this man—"One summer-day I chanced to see"—but right before he tells that part, he interrupts the legend of the man to say:

My gentle reader, I perceive

How patiently you've waited,

And I'm afraid that you expect

Some tale will be related.

O reader! had you in your mind

Such stores as silent thought can bring,

O gentle reader! you would find

A tale in every thing.

What more I have to say is short,

I hope you'll kindly take it;

It is no tale; but should you think,

Perhaps a tale you'll make it.

Wordsworth is shifting potential disappointment into an accusation against the reader. You can't find a tale in every thing? Wordsworth can! What's more, we learn in "Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey" that "We see into the life of things." There is implicit in all of this a promise that such tranquil recollection is possible, and that it becomes, in turn, "tranquil restoration."

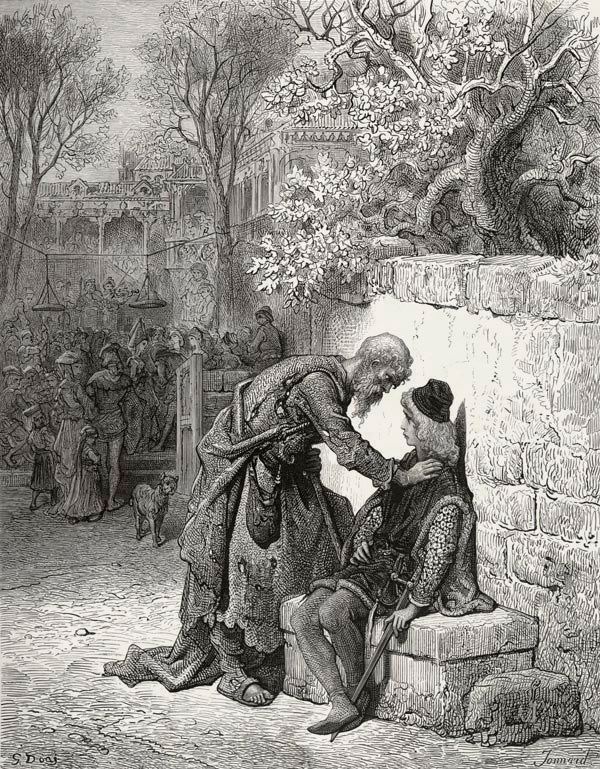

Lyrical Ballad largely collects simple stories of encounters with worlds and feelings which seemed to be disappearing from popular consideration. It is also home to several wild poems, most notably Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner." Over the course of Lyrical Ballads, we see this "ancient mariner" hold still a man by the power of his glittering eye, the mariner himself bound to tell his tale, and having out his will on a terrified wedding guest who must hear him out.

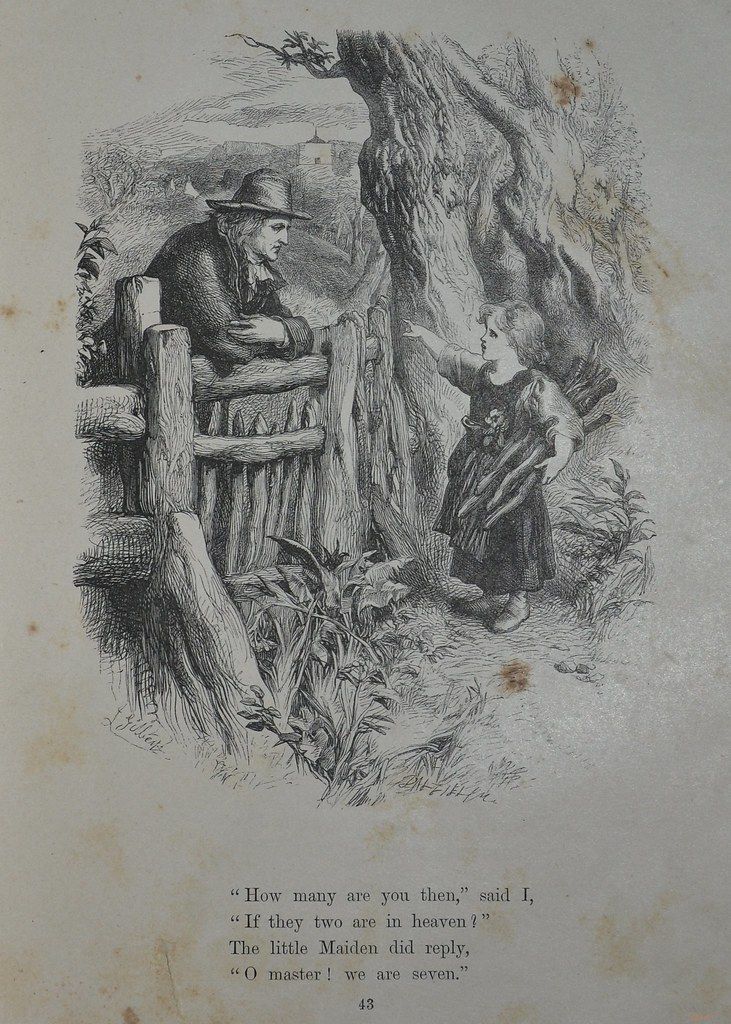

Also in the collection, we see another man stopped in his tracks by an eight year-old girl. In Wordsworth's "We Are Seven," the speaker insists to the girl that she and her siblings total five, as two are now dead, and then concludes:

'Twas throwing words away; for still

The little Maid would have her will,

And said, "Nay, we are seven!"

We can see clearly the supernatural power of the ancient mariner, but we may not so readily see into the life of things when it comes to the girl or the unhewn stones. By force of continual reading—by delivering lyrical ballad after lyrical ballad—Wordsworth hopes to transform his reader. The reason you can't see a tale in his poem or find the story of Michael lacking is because something has been lost.

Wordsworth, meanwhile, begins Volume I with two connected poems: "Expostulation and Reply" and "The Tables Turned; an Evening Scene, on the same subject." Just as you are starting on this two-volume book, Wordsworth insists that the ultimate goal is that you will be able to move away from books and see something in the world for yourself:

Enough of science and of art;

Close up these barren leaves;

Come forth, and bring with you a heart

That watches and receives.

If you were ready to do this at the start, you might very well take his advice, but Wordsworth trusts first that the average reader will not be ready, and second that he will eventually win over at least some readers. If Wordsworth's readership were already Wordsworthians, they might never get to Volume II, but he understood, "Every great and original writer, in proportion as he is great and original, must himself create the taste by which he is to be relished."

That is why you must go through the process of reading Lyrical Ballads. John Keats wrote in a letter, "Do you not see how necessary a World of Pains and troubles is to school an Intelligence and make it a soul?" Like Wordsworth before him, though, poetry promised another way to train a heart or soul to watch and receive. Wordsworth and Coleridge craft an incredible collection of poetic efforts in this endeavor with Lyrical Ballads. One famous technique of Wordsworth's here is that he sought to use, as much as possible, "the real language of men in a state of vivid sensation." More lofty poetry, he found, would not do. The reader must be brought to these vivid sensations in "real language," "ungarnish'd with events." Wordsworth cannot hand you the full tale, and so his poem can neither be fully lyric or fully ballad; you must navigate the two and learn to see for yourself.

If you'd like to explore the collection yourself, I've prepared a curated selection in five parts, detailed below. If you'd like to join me to discuss each part over five evenings, you can join me for Crash Course on English Poetry from July 11 to July 15. Either way, please consider reading some of the poems, and reach out with your thoughts!

Perhaps a Tale You’ll Make It

In his preface to the second edition of Lyrical Ballads, William Wordsworth warns that the reader will find few personifications of abstract ideas, for “in these Poems I propose to myself to imitate, and, as far as possible, to adopt the very language of men.” Against what expectation is Wordsworth writing and how does he pursue his poetic revolution? Start with the opening two poems of this second edition (“Expostulation and Reply” and “The Tables Turned”), a short poem on gossip (“The Thorn”), and a short poem which pleads for you to see past the lack of tale related (“Simon Lee, the old Huntsman”).

The Mariner Hath His Will

Though Wordsworth contributed the majority of poems and later preface to Lyrical Ballads, the work was a collaborative effort with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who contributed one of the book’s most famous poems: “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” Alongside Coleridge’s cursed, albatross-carrying mariner, we will also read another short Wordsworth poem. The young girl in “We Are Seven” lacks the mariner’s overt supernaturalism, but is perhaps just as cursed—and just as willful.

To Be a Jarring and a Dissonant Thing

Getting more into the work’s social concerns, Coleridge addresses in “The Dungeon” the impact of imprisonment on criminals, while Wordsworth in “The Old Cumberland Beggar” reacts to efforts to set the nation’s growing poor out of view, and in “Michael” to constraints on pastoral life. Expressing the value of natural scenes for which these poets are more widely known, these poems also demonstrate their deep perception of human concerns.

The Touch of Earthly Years

Across several poems in Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth writes of a lost love figure he calls Lucy. Of these, read “She Dwelt among the Untrodden Ways” and “A Slumber did my Spirit Seal.” Again in the spirit of this collaborative collection, however, couple these poems of loss with another Wordsworth poem on untimely death (“Animal Tranquillity and Decay”) and a more hopeful reframing by Coleridge in “The Nightingale.”

We See Into the Life of Things

Concluding both the first edition of Lyrical Ballads and the first volume of the second edition, “Lines written above Tintern Abbey” merges personal recollection with a poetically crucial desire for a better future for others. Near the start of Volume II, however, we return to untimely death—and echoing nature—with “There was a Boy.” Reading these poems side-by-side, you might gather some closing thoughts on Lyrical Ballads and where poetry goes from there.