Always Again Another Bloomsday

Falling for, or falling with, "Sirens" in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake.

The "Sirens" chapter of James Joyce's novel Ulysses opens with an overture. As is standard with Ulysses, each chapter is very distinct in style, in accordance with the form. Here the chapter is about music, and so the text itself is also musical. As the title suggests, though, the music is also dangerous. Even as we enjoy it, we are like Odysseus tied to his ship as the sirens tempt him to lead his ship astray, never to return home. I had a physiological reaction in first reading this chapter. I felt myself twisting and turning. This was the result of the pleasure of the text's sounds, combined with an intellectual pleasure of Joyce's masterful weaving of John Milton's Paradise Lost – the story of Adam and Eve's Fall and removal from Eden – in with both his own story and Homer's.

Ulysses is from 1922. It takes place, notably, on a single day in 1904: June 16th. This setting commemorates James Joyce's first outing with Nora Barnacle. The two married in 1931. The date and its literary parallel are now celebrated annually as Bloomsday, in honor of Ulysses' central couple, Leopold and Molly Bloom. They are, in some ways, James and Nora, as well as Adam and Eve. We are an Adam or an Eve, too, and so we celebrate. (The holiday is not strictly understood in those terms, though many may often feel it in those terms.) In order to understand why we celebrate, when Adam and Eve committed the original sin, leading to the Fall of man, and why I felt such excitement around Joyce's use of this story, we will take a very guided tour through one chapter each of Ulysses and Finnegans Wake.

My great blue bedroom, the air so quiet, scarce a cloud. In peace and silence. I could have stayed up there for always only. It's something fails us. First we feel. Then we fall. And let her rain now if she likes. Gently or strongly as she likes.

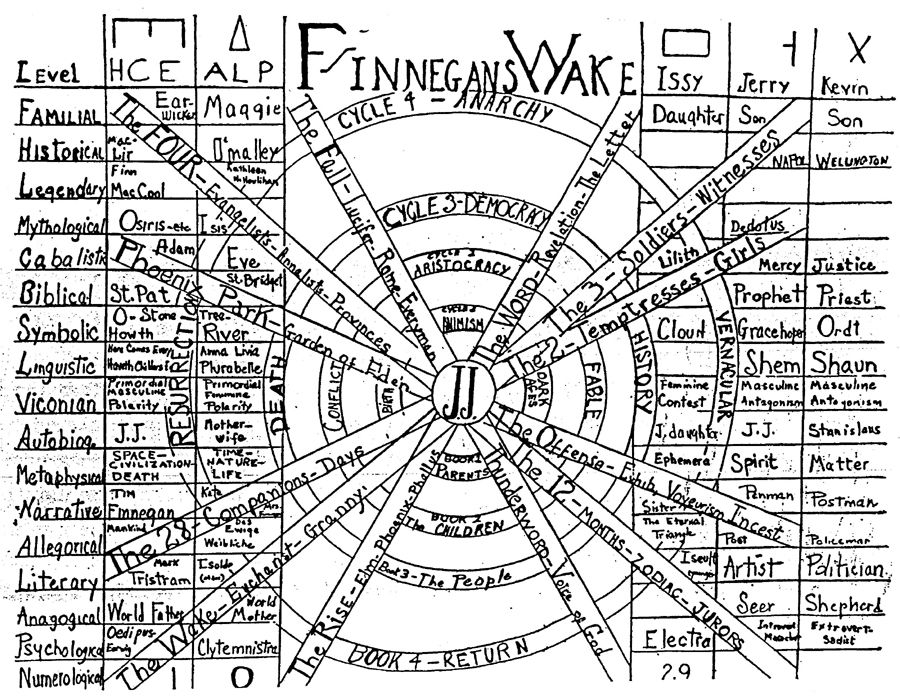

This passage, from the closing chapter of Finnegans Wake, contains one of many references to falling. The whole work is structured around an endless series of falling and rising, with transformation in between such that the result is not a perfect loop but continually new cycles. Here, ALP (Anna Livia Plurabelle, the mother, the wife, the River Liffey, Eve, time, life, Isolde, etc.) recalls an originating state of Paradise and then a fall – as with the Fall of Adam and Eve. In this sense of aging and raining down of feeling, we also see a transformation from Issy (the daughter, the cloud) into ALP (the river). László Moholy-Nagy attempted to sketch some of this out in 1946:

This chart goes much deeper than we will today, though. We are only interested in the temptation of and by Eve.

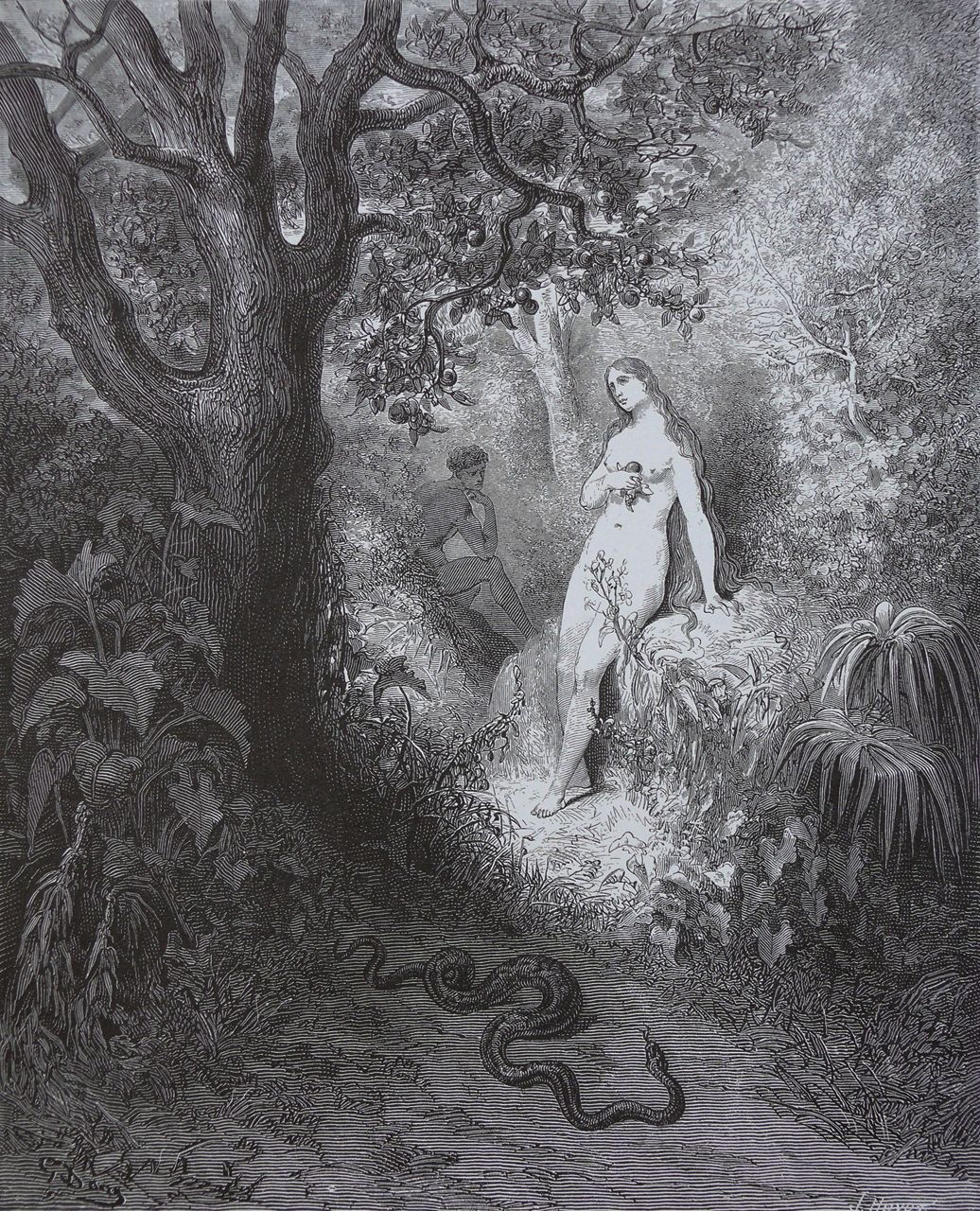

In Paradise Lost, John Milton presents two falls: first of Lucifer, who refuses subservience to God and is cast out of Heaven, and then Adam and Eve, tempted in turn by Lucifer to disobey God's will. Before the Fall, Adam and Eve lived in the Paradise of Eden. Upon eating the forbidden fruit, they are kicked out of Eden and so introduced to experiences such as suffering and death. As I write in discussing Coleridge's use of Milton to discuss "a love of future existence,"

On the surface, the story of Adam and Eve is tragic (bringing death into the world, and the pains of childbirth), but in doing so it also brings the promise of successive generations.

In the earlier quote from Finnegans Wake, ALP recalls an early state of Paradise in which "I could have stayed up there for always only," but then you fall into existence, and her children fall, in turn, from her. We are born with original sin from the Fall of Adam and Eve, but the idea also reflects something which happens to us in life as we fall from innocence into knowledge.

In "Sirens," Bloom is tempted to sin – lust and gluttony primarily – as he sits and listens to music, just as his literary parallel Odysseus was tempted by the Siren song. In The Odyssey, the legendary threat of the Sirens was already understood in a postlapsarian (after the Fall) way:

that man

who unsuspecting approaches them, and listens to the Sirens

singing, has no prospect of coming home and delighting

his wife and little children as they stand about him in greeting.

It would not be the falling of all mankind, which knows now the joy of family, and holds loss of this rather than of innocence as the highest fear. It would, however, be a personal falling, and even a mighty hero such as Odysseus is not immune to the temptation. Circe advises Odysseus to plug his crew's ears with wax so they cannot hear the song, but as leader, he should hear and let them know when the song begins and when they are safely past it. He does so by having himself tied tightly to the ship, and so gets to enjoy the song and share a filtered version, just as The Odyssey is itself then passed down orally. As a foundational literary text, this sacrificial role becomes a model for the literary arts.

In Joyce's view, this intense personal feeling becoming narrative extends explicitly to his own experiences, such as with Nora. As seen in the chart above, one of the levels of the text (left-most column) is autobiographical, and in this scheme, James is HCE, Nora is ALP, and their daughter is Issy, the daughter of HCE and ALP. To complicate things, James is also Shem, the older son, and James's younger brother Stanislaus is Shaun, the younger son. These child characters – and the way in which the two generations cyclically interchange – will be key to when we discuss Finnegans Wake, but the earlier text, Ulysses, will provide an easier way in.

In the overture to "Sirens," we hear a "Hissss." This is music, waves, and Lucifer disguised as a snake in the Garden of Eden. Then, "All gone. All fallen." The overture gives a glimpse, and the rest of the chapter shows us this process in detail. We are not at sea or in a garden, but inside a hotel in Dublin. There is music, drinking, food, and talk. The waiter is, of course, deaf, like Odysseus' crew, or how else could he bear it?

Like I described with The Odyssey, the Fall occurs within "Sirens," but Leopold Bloom is already fallen at the start of the chapter. He walks around "bearing in his breast the sweets of sin" and "in memory bearing sweet sinful words." On the autobiographical end, "sweet sinful words" can certainly be found in Joyce's letters to Nora. Among more graphic details, he writes, "Let every sentence be full of dirty immodest words and sounds. They are all lovely to hear and to see on paper even but the dirtiest are the most beautiful." Joyce is joyously postlapsarian, for reasons which will become clear.

Since we start the chapter as post-Fall beings, there are references to that climactic moment before it directly occurs. At one moment, Bloom (as crying "Bloowhose") thinks, "Bloowhose dark eye read Aaron Figatner’s name. Why do I always think Figather? Gathering figs I think." He thinks indirectly of Adam and Eve gathering figs to cover their nakedness, of which they were newly aware due to eating of the tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. When God confronts them, He addresses this knowledge specifically, and just as their shame drove them to gather the figs, through their shame they cannot hide the truth.

In a conversation which Bloom later overhears, a man asks a woman, "Did she fall or was she pushed?" They are not speaking of the Fall in a literal sense, but that is the effect of the exchange within the ongoing thought. This is a key question in the theological story: Was Eve free to act in a state of innocence and so blameful, or was she corrupted by the external influence of Lucifer? If the point is against seeking knowledge of good and evil, however, perhaps we shouldn't press this question. The woman, accordingly, answers, "Ask no question and you'll hear no lies."

Another character soon enters, with "red lugs and bulging apple" – the Adam's apple in his throat. Though this feature is so overtly present on him, he is fallen and cannot help but ask, "Something to eat?" The apple ever-lodged in his throat, he continually wants more. The Fall was not just a loss, though, but brought new things into the world. Foremost is knowledge. It was sinful to obtain, but like the sacrifice of Odysseus bearing the Siren's song, perhaps worthwhile. The temptation of Odysseus was similarly based in the promise of new knowledge: "Over all the generous earth we know everything that happens," the Sirens tell him (Lattimore translation).

Milton's poetic task in Paradise Lost was to "justify the ways of God to men," but justifying the ways of humans in the story came later. In the British Romantic era, William Blake writes in "The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,"

Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence.

From these contraries spring what the religious call Good and Evil. Good is the passive that obeys Reason. Evil is the active springing from Energy.

To Blake, the evil acquired by man in the original sin is foundational for freedom and creative energy. Because it is so central to artists such as himself, he even retroactively attributes his view of Lucifer as hero to Milton, saying he wrote "at liberty when of Devils and Hell" "because he was a true Poet, and of the Devil’s party without knowing it." This is also seen through Percy Shelley revising Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound, in light of reading Milton's Satan as hero, as Prometheus Unbound. Prometheus, too, sacrificed himself to bring knowledge to mankind, and was in turn bound like Odysseus.

Because Prometheus is bound, Shelley is free to lounge and think and write. He has knowledge, can seek new knowledge, and can share that knowledge. The Romantic view is that the Fall was a happy Fall. On the American side, Walt Whitman speaks to this even more directly in "One Hour to Madness and Joy":

To ascend—to leap to the heavens of the love indicated to me!

To rise thither with my inebriate Soul!

To be lost, if it must be so!

To feed the remainder of life with one hour of fulness and freedom!

With one brief hour of madness and joy.

He is "lost" (referencing Milton), but he has "freedom" and "joy." This is also one of his "Children of Adam" poems, a cluster overall celebrating that earlier discussed benefit of the Fall, which is birth and the possibility of successive generations. In Finnegans Wake, one of the two references to "Whitman" found through the search tool Fweets of Fin (the return of those "sweets of sin," as imagined with a long s) appears in the core chapter discussed below: "old Whiteman self." The other is a direct quote of one of Whitman's most famous titles: "Out of the cradle endlessly rocking." As Whitman explores (through sea imagery, no less), we suffer through love and death, but we create both art and new life. We fall, but we also rise, rocking back and forth endlessly between these two states. This is the key lesson of Finnegans Wake, and of Bloomsday.

The Fall is a fall (in the classic view) from innocence and happiness into suffering, grief, and death. The Fall is also a rise (in the Romantic view) – the emergence of new freedom, to think and to act, and the origin of the possibility of true happiness rather than its loss. For Joyce, falling and rising are part of the same cycle. First we feel (a postlapsarian state of intense, unrestrained emotion), then we fall.

With Ulysses, we see this play out for one person on one day. Odysseus is our great mythological and literary model, and the question for us now is: How can we find our way back home, to our wife standing about us in greeting? (Joyce, notably, also deeply considers her side: How can Molly continually greet her Bloom?) With Finnegans Wake, the question expands. Now it is: How can we all collectively continue to rise and fall, and rise in falling? Where Paradise Lost ends with Adam and Eve "hand in hand with wandring steps and slow" leaving Eden together, Finnegans Wake ends with ALP "a way a lone." She has her memory, however, and she is writing. This memory is personal, literary, mythological, cultural, and so on. With all of this, we inevitably loop back to the beginning, "past Eve and Adam's":

A gull. Gulls. Far calls. Coming, far! End here. Us then. Finn, again! Take. Bussoftlhee, mememormee! Till thousendsthee. Lps. The keys to. Given! A way a lone a last a loved a long the

riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

You cannot have this rise, however, without the Fall.

Returning to the "Sirens" in Ulysses, sinfulness is everywhere. As Bloom sits, eavesdropping on conversations and listening to live music, he is filled with lust and gluttony, and these two merge. They are, after all, from the one original sin:

Pat served uncovered dishes. Leopold cut liverslices. As said before he ate with relish the inner organs, nutty gizzards, fried cods’roes while Richie Goulding, Collis, Ward ate steak and kidney, steak then kidney, bite by bite of pie he ate Bloom ate they ate.

Bloom with Goulding, married in silence, ate. Dinners fit for princes.

We eat the apple, but we also return here to the Prometheus myth. He was not just bound, but each day an eagle would come and eat his liver, the core of his feelings. In an endless cycle, the liver would regrow each night, just so it could be painfully consumed directly from his body in the morning. Bloom and Goulding are here the eagle, with Goulding's breath later described as "birdsweet" (the sweets of sin). As fallen beings, we continue to enact the original sin on each other endlessly. As the music begins, Bloom is overcome with emotion, imagining all men as the harps on which lovely ladies play, "I. He. Old. Young." He does not fail, however, to keep thinking of his gravy amidst this.

Feeling so strongly, they fall. Goulding says to Bloom, "All is lost now." It is not, however, the food nor the music nor the lust alone. Bloom thinks, "Words? Music? No: it's what's behind." Behind all music is our being lost. First we feel, then we fall, then the rain.

Increasingly in succeeding pages, we are drawn out of the scene and into Bloom's head. He contemplates first the cruelty of longing and loss, which is also (as in the Fall) death and suffering:

Cruel it seems. Let people get fond of each other : lure them on. Then tear asunder. Death. Explos. Knock on the head. Outtohelloutofthat. Human life. Dignam. Ugh, that rat’s tail wriggling! Five bob I gave. Corpus paradisum. Corncrake croaker : belly like a poisoned pup. Gone. They sing. Forgotten. I too. And one day she with. Leave her : get tired. Suffer then. Snivel. Big Spanishy eyes goggling at nothing. Her wavyavyeavyheavyeavyevyevy hair un comb : ’d.

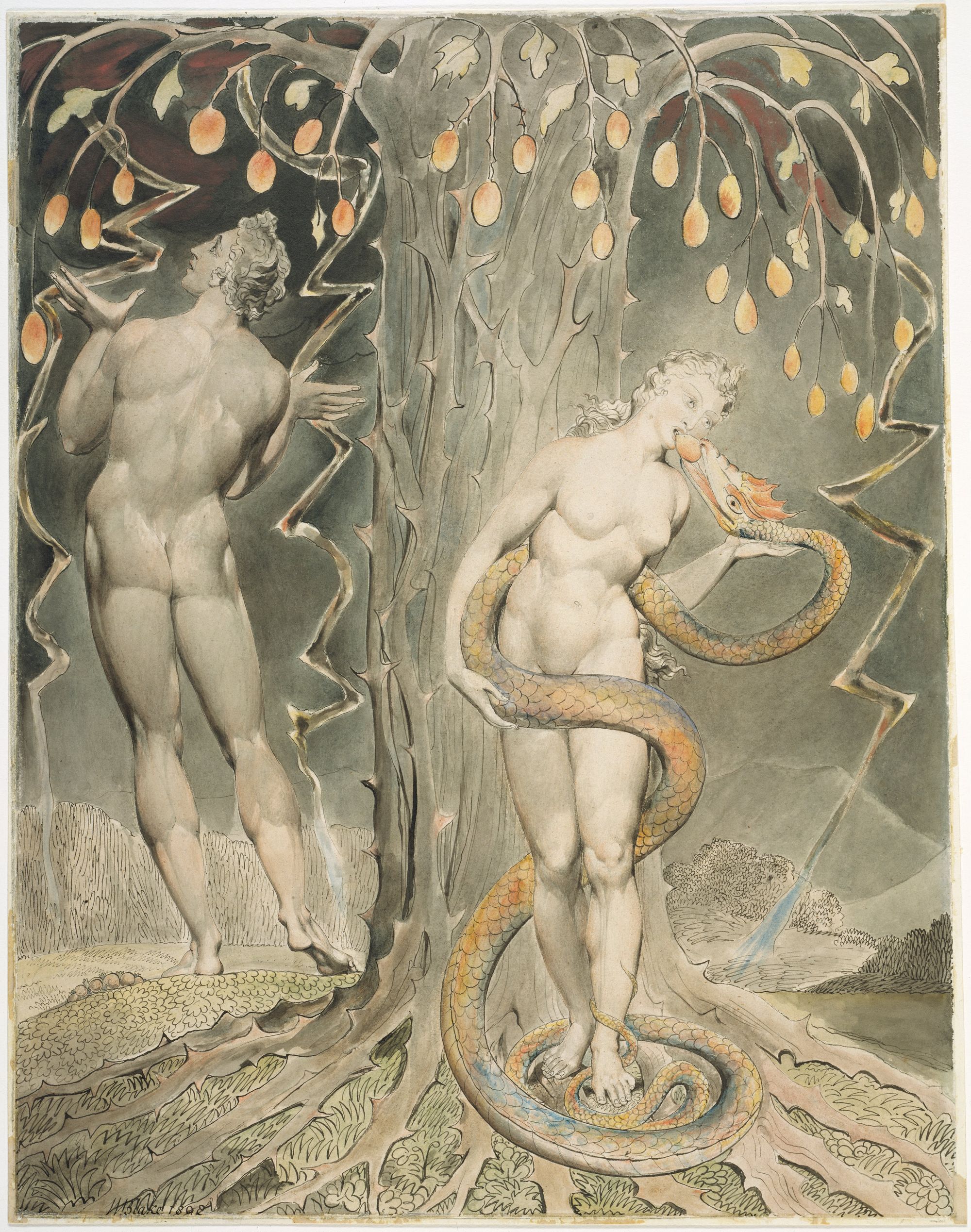

As he contemplates this, he is also admiring a woman, particularly her hair, which is "wavyavyeavyheavyeavyevyevy" and "un comb : 'd." As suggested in the latter quote (literally and stylistically), her hair is a wild mess. In Milton, this is Eve's "wanton ringlets," which are in direct parallel with the "wanton growth" of the garden. It should be no surprise, then, that Milton also compares her hair with the heavy waves (flowing outwardly and into each other) of the sea. The "murmuring" movement of the water (a term also picked up prominently by the Romantics) is in Milton a source of danger. Because we find the sound so lovely, sailors may be lulled into calm, only to be wrecked by tempest.

Bloom then becomes not so passive in his encounter with the music. He begins, instead, to think of it in mathematical terms. Hearing Goulding refer to a "number" in an opera, Bloom thinks,

Numbers it is. All music when you come to think. Two multiplied by two divided by half is twice one. Vibrations : chords those are. One plus two plus six is seven. Do anything you like with figures juggling. Always find out this equal to that, symmetry under a cemetery wall. He doesn’t see my mourning. Callous : all for his own gut. Musemathematics. And you think you’re listening to the etherial. But suppose you said it like : Martha, seven times nine minus x is thirtyfive thousand. Fall quite flat. It’s on account of the sounds it is.

The mathematics provides a fixed foundation for the experience, but it is only "etherial" through the sound in which we experience it. Similarly mathematical and with potential for beauty is human existence. The Fall brings death, but also new life. Adam and Eve are two, then multiply in having two children. When Adam and Eve die, this total is divided by half, but this is still twice one – the lone Adam in Eden before the creation of Eve. As this all equals out, there is "symmetry under a cemetery wall." We grieve on a small scale, but feel something greater in the larger scales of history.

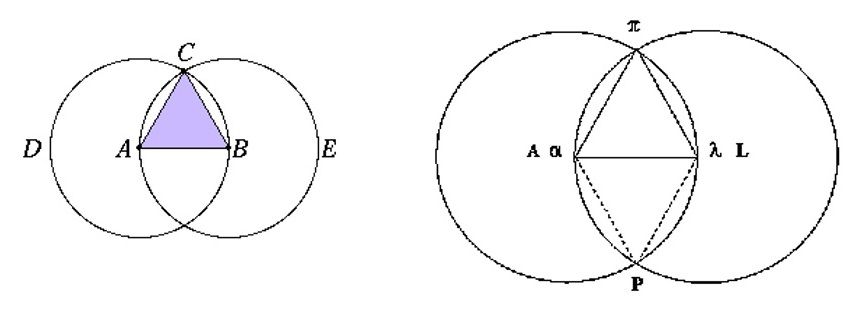

The allure of mathematics returns in Finnegans Wake. Book II, Chapter 2 details the children at night, studying before bed. They are up in their bedroom, with the adults in a floor below. One lesson involves proving Euclid.

In the original diagram, only the upper triangle is relevant to the proof, but the children proceed to add a parallel lower triangle in dotted lines. As described in the text, they join the points and then "pull loose by dotties":

Now, to compleat anglers, beloved bironthiarn and hushtokan hishtakatsch, join alfa pea and pull loose by dotties and, to be more sparematically logoical, eelpie and paleale by trunkles.

This mirroring reflects a general dynamic throughout the chapter – such as in the physical relation between the kids and adults, the textual relation between Shem and Shaun in the margins and Issy in the footnotes, and in more metaphorical ways – that as happens above, also happens below. This is described as, "The tasks above are as the flasks below," referring most directly to the homework tasks above and the drinking occurring below. The drunken night of the parents is not far off, however, from where the kids are heading. In pulling loose those dotties, they do not just learn geometric truths, but fall into sexual knowledge.

In line with Blake's "Marriage of Heaven and Hell," Joyce presents the discovery of sexual knowledge as simultaneously good and evil. Asking "Qued?" – that which is to be proved (Q.E.D.) but also "evil" – the boys instead see the diagram as an abstract visual depiction rather than mathematical relations: "Mother of us all! O, dear me, look at that now!" Shem says. The more innocent Shaun sees it as a skull. What Shem is seeing is, instead, genitalia, and he commands his brother to look again and, "See her good." The diagram can be seen as both vagina and (as in the dotted lines) uterus. While the brothers take pages sorting this out, Issy notices almost right away. Right below the diagram, we see: "Dawn gives rise. Lo, lo, lives love! Eve takes fall." Issy is, naturally, intimately aware of female genitalia, but like Eve before the Fall, she did not know she was naked. A few lines down, then, we see "in Fig., the forest," and more explicitly later: "I'll make you to see figuratleavely the whome of your eternal geomater" ("I'll make you to see figuratively [in a geometric figure; in fig leaves] the womb/home of your eternal earth-mother"). Issy is, in this way, connected with her mother, ALP (whose genitalia is depicted in the diagram, per the P added to complete the dotted lines), as all women are connected in a great lineage back to Eve, whose sin brought into being the pain of childbirth and death.

Just as Issy and her mother form this succession, the information is passed from one brother to the other. None of this is new. The knowledge is no longer the product of a "forbidden fruit." Here in this chapter it is a "fore-bitten fruit." This has all happened before, and each generation is newly innocent and newly falls. With knowledge comes strife. Shaun strikes Shem, just as (with the sons of Adam and Eve) Cain slays Abel, but the story of Finnegans Wake is on a grander scale. Shem is able to forgive his brother and they are "singulfied," which is to say they become one (and so one is slain, in a sense). Awoken to sexual knowledge, they are now a young Adam or a young HCE, just as Issy is a young ALP. They must take on these adult roles, with all their complications as distilled in our myths.

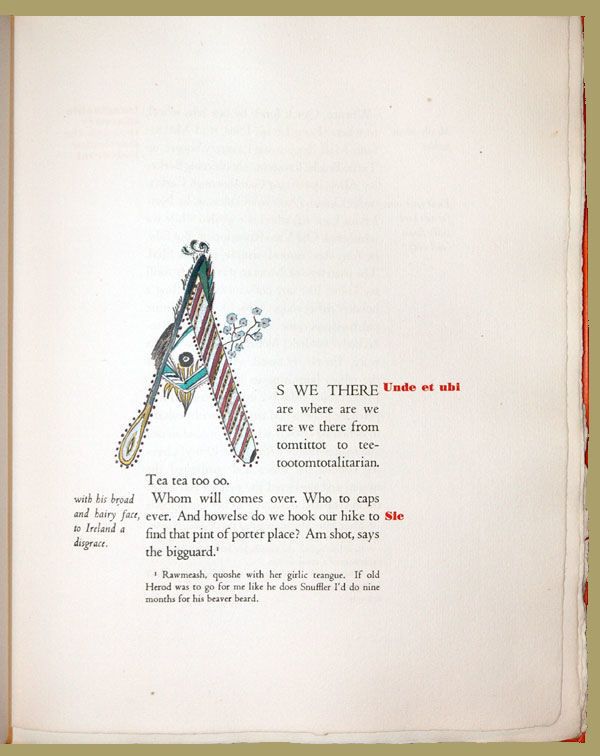

Issy and ALP are Eves. As a water being (the River Liffey), ALP (and so eventually Issy) is also a Siren figure. As published initially on its own, this chapter is "Storiella As She Is Syung." Issy is the titular Storiella figure, singing. As noted, she sits at the foot of each page with her notes. Very early on, she is shown to be acutely aware of expectations that she marry, and as she falls, she grows to embrace her role as the sort of temptress understood through the Sirens or Eve. She thinks, "Will you walk into my wavetrap? Said the spiter to the shy." The relation between spider and fly also becomes that between a woman and a shy man, with the woman acting explicitly out of "spite" to some extent. This image returns later, connected back with the diagram, as she is "the spidsiest of her trickkikant," referring at the end of that phrase to a triangle. On the autobiographical level, James and Nora's daughter Lucia had her own fallings, but provided illustrations for the Works in Progress that became Finnegans Wake. For "Storiella As She Is Syung," she illustrated the chapter's opening letter (A) as an elaborate triangle, specifically in the image of a compass, the tool with which one would draw the diagram's circles.

This negative image of the spider-Siren is only one half of the fall and rise, though. James Joyce, loving Nora as he did and Lucia as he did, gives Issy the last word on every page of this chapter, and so, of course, with the chapter overall. In the novel's conclusion, similarly, we end with ALP's letter. Earlier, Molly Bloom got the last word of Ulysses through her soliloquy. In the end, Eve must convince Adam to Fall – for her, with her – or we can never rise.

Issy is a danger, but this is always in a cycle which promises an angelic return. Toward the end of Paradise Lost, it is the Archangel Michael who shows Adam a vision of the future. He sees another Fall in the Great Flood, but also potential redemption of mankind through Jesus Christ. In Finnegans Wake, it is not Adam who Michael gives his vision of the future to, but Issy. She speaks to him at first careless of danger: "Well, of course, it's awful angelous. Still I don't feel it's so dangelous" (the dangerous dangling of the apple). This is when he gives her the vision of "whome" of her "eternal geomater." She then becomes not the spider, but the serpent: "Hissss!, Arrah, go on! Fin for fun!" In falling, though, is that the end of fun ("Fin for fun"), or only the beginning? In Finnegans Wake, the funeral is also "funferal" (fun for all). There is, as we learned in Ulysses, "symmetry under a cemetery wall" (and "The tasks above are as the flasks below"). Issy's "Hissss" is a precise copy of the one we saw earlier in Ulysses, down the exact same numbers of S's (the letter found in every word in "Storiella As She Is Syung"), but there is another path of return to that chapter. In Milton, when Michael tells Adam of the "great Messiah," he declares,

By his prescript a Sanctuary is fram'd

Of Cedar, overlaid with Gold

This cedar-gold image becomes the remarkably Eve-like hair Bloom admires in "Sirens." As described in the chapter's opening words, it is "Bronze by gold," a visual refrain repeated dozens of times throughout the chapter. Redemption is premised on sin, and so Bloom's sinful gaze, in its "sweets of sin," bears this image of Michael's prophesy. As Bloom thinks later, "For all things dying, for all things born ... Because their wombs." This is the legacy of the Fall. We are lost, but return again always to "Eve and Adam's" (immediately in the novel a reversal of the much more common "Adam and Eve").

Eve and Adam are not a lost past, but us now, and our children, and endless generations hence. James Joyce spent decades of life to write for us a framework in which we can see this as true, just as it was for Nora and himself. We get to celebrate that new prophecy of redemption every year. That's Bloomsday.

To learn more about James Joyce, Romantic theories, and the wonder of successive generations, subscribe to my free monthly newsletter (be sure to confirm). I bring together new literature, literary history, and computer-based writing in conversation: