Anti-Text Revolution: Why and How

PreCursor Monthly – April 2021

The following post must be read, but maybe it will be the last thing you read.

I will explain more below, but you might begin by wondering how I will keep up a literary newsletter while rejecting text. I am excited to announce that following a possible grant from the Filmgoers Association of America's Lower 48, Inc., PreCursor Poets is now PreCursor Auteurs. Expect all the insight you know and love, but for film, and with more hot takes.

Meanwhile, my podcast, Double Vision – which previously explored moments of synchronicity in literature-film pairs released in very close proximity – will be rebranded as Two Reel. Join me as I explore all the most exciting possible double features in the history of cinema. My first episode will cover the same-day release of David Fincher's cult classic Fight Club and David Lynch's under-recognized The Straight Story. No Goliaths here, folks.

Before you go sharing this news too widely, note that the money is not finalized. If I am ultimately not selected for this prestigious grant of $100, I will be forced to go back to literature, and you can expect a revised PreCursor Monthly on April 15th.

Barren Leaves and the Threat of Reading

The expansion of literacy and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race.

In Lyrical Ballads, the poet William Wordsworth is combining the rising text-based form of the lyric with the fading communal, oral tradition of the ballad. Writing in this context of rising literacy, Wordsworth astutely comments in "The Tables Turned":

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Misshapes the beauteous forms of things;

—We murder to dissect.

Enough of science and of art;

Close up these barren leaves;

Come forth, and bring with you a heart

That watches and receives.

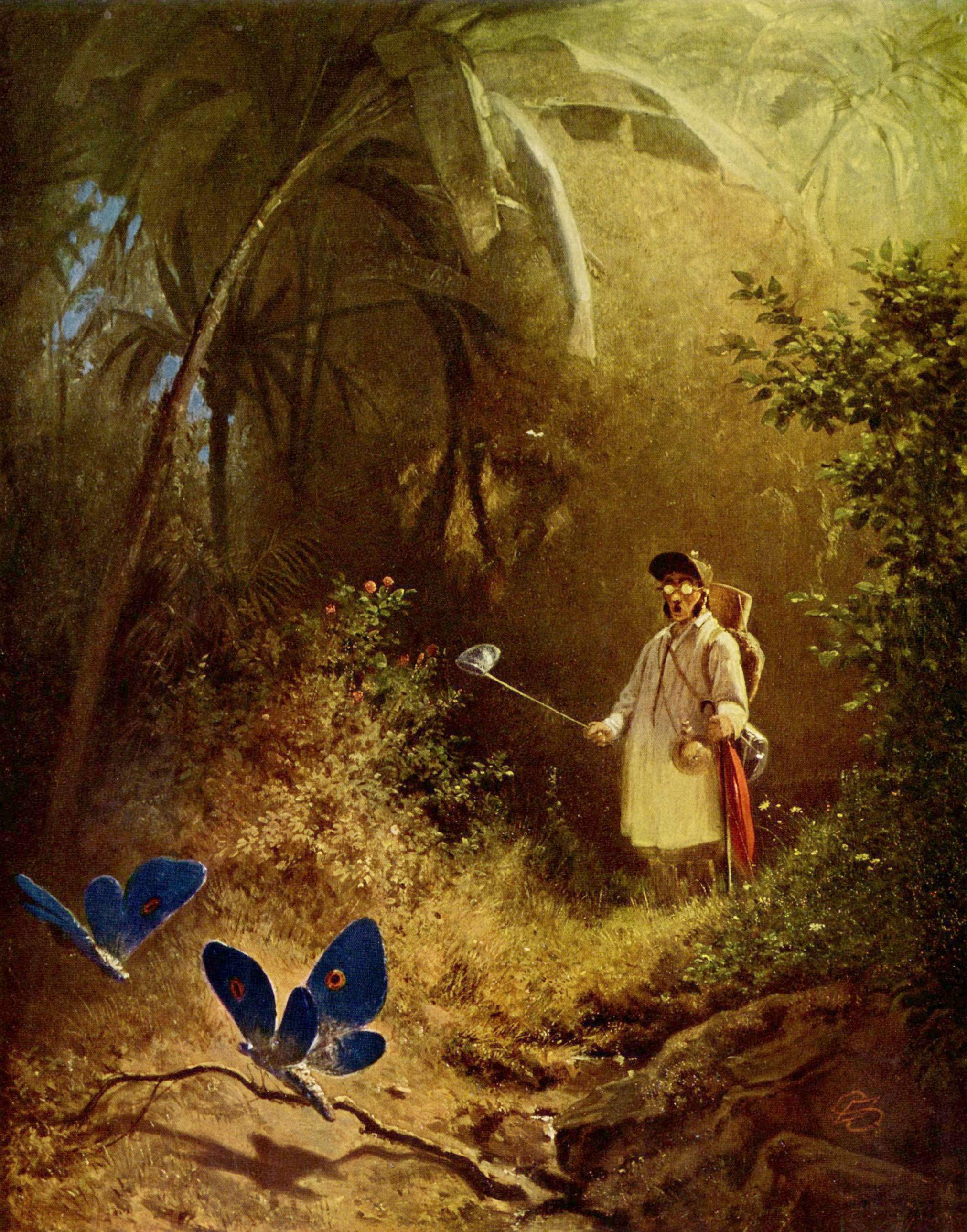

Wordsworth is reacting to a growing impulse to break things down into scientific forms rather than simply receiving their existing "beauteous forms," for which our imaginative faculties are naturally prepared. It is through such imaginative perception that, in "To a Butterfly," he finds the insect to be "Historian of my infancy!" Instead of tranquilly receiving this sort of deeply personal knowledge, however, he finds people driven repeatedly to kill butterflies and more, simply to dissect the creature to discover nothing of real value.

Importantly, in his closing stanza, Wordsworth does not simply say "Enough of science." He adds "and of art." Those barren leaves, too, distract us from truly connecting with others and with the world. As I discussed recently with Adam Jesionowski, the film Ex Machina offers an interesting look into how an obsession with technological progress blinds the film's two competing human characters to each other and their beautiful surroundings.

In Ex Machina, the head of Blue Book – a fictional blend of Google and Facebook – creates an artificially intelligent robot, and brings in a lone employee to test it. The AI is based on the accumulation of all online searches, social media use, and an extensive archive of audio and video from mobile devices which are secretly always recording. The film comes out a year after Edward Snowden revealed some of the inner workings of the NSA. One of the biggest leaks is the "PRISM" surveillance system, a name which was previously used for an AI system tasked with predicting the future to determine economic and social policy in the foundational puzzleless interactive fiction work A Mind Forever Voyaging.

Facebook, meanwhile, was launched on February 4, 2004, the same day the Pentagon canceled its LifeLog project, "an ambitious effort to build a database tracking a person's entire existence." This just goes to show the incredible luck of Mark Zuckerberg, who was now free to crowdsource roughly the same project without this mighty competition. Though later branching out in acquiring the image-based service Instagram and trying to push video, the service is primarily dependent upon our reading and writing practices. Even on Instagram, the navigation of pseudonyms, captions, hashtags, text-based comments, and so on structure the full experience, particularly the social aspects of the network.

More fundamental than explicit "digital literacy" skills are our general literacy skills, built up over years through a literary education. One of the most frequently recurring elements of such an education today is a process of close reading, a practice of intense focus on just the text of a work, attempting to exhaust the meanings present in the language and form. Though this may seem obvious to us now (perhaps even inescapable), the method was pushed into its heavy use in the early 20th century by a group known as the New Critics. As explained by John Kimsey, New Criticism at Yale University eventually served as a radical pipeline to the Central Intelligence Agency due to the work of James Angelton, poet and 21-year chief of CIA Counterintelligence. As we can see in the weighty dissertations produced daily even by teenagers in which the personal histories (electronically archived) of strangers are exhausted to prove the rightful judgement of their fate, there is a natural continuity between close reading as practiced on poetry and counterintelligence work.

(Though that specific New Criticism scene is gone, the CIA continues to influence literature, such as through the Iowa Writers' Workshop and the Poetry Foundation.)

Ex Machina dramatizes the repurposing of our information archives as part of a competition between people as if they were playing chess. At the same time, the director Alex Garland keeps showing us wide shots of the sublime natural scene from which these characters are isolated in the enclosed, artificially-lit home. An important question in the imagined Turing Test is what the AI would make of first encountering a blue sky, yet neither Caleb nor Nathan dedicate their own attention toward that subject.

One of the narrative precursors to the film is Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein, a widely adapted work about a scientist pushing himself beyond all mortal limits in his ambitious quest to create truly independent life. In Shelley's novel, Frankenstein's creation learns through a mix of reading books and natural discovery. Frankenstein himself edits his narrative to heighten the rhetorical power of his dialogue and situates his most dramatic encounters among the heights of natural power – "the tempest so beautiful yet terrific" – but is not conscious of this dynamic. All he can see is the need to kill his creature, whose body he made from assorted parts of the dead. In that earlier moment of creation as well, he was figuratively blind. He writes that he "had selected his features as beautiful," yet despite closely working on the body for months, it is only once the body starts moving that Frankenstein realizes how deeply he has failed.

In the 1935 film Bride of Frankenstein, the body parts are not collected from random scattered remains. A young woman is murdered to quickly provide the right bodily frame. In this telling, one of the terrors of the animating power of Frankenstein is that you might be killed and repurposed. For narrative purposes, the concept of AI offers refreshes this old fear. We murder to dissect, and this being running on all the data we harvest and feed into its wetware might opt to murder us in turn.

Outward Consumption vs. Inward Creation

Given the threat of reading presented above, please consider instead the "jocund company" of daffodils. Everything you need to know in this life is present in that scene and can be replayed "upon that inward eye."

Lars von Trier demonstrated this as well in his 2000 musical film Dancer in the Dark. In support of the fact that we don't even really need to see that much, Trier filmed using low-end digital cameras.

The film stars Björk as Selma Ježková, a blind immigrant factory worker who also experiences vivid daydreams. Having lost her sight, she becomes more attentive to her hearing, and starts to find music in the everyday sounds of the world, including the industrial noises of machines and trains. Unable to see Hollywood musicals, she attends the cinema with a friend who describes the movies to her, and these descriptions fuel Selma's imagination. As I wrote about previously regarding Abigail Williams' The Social Life of Books, books were not always something one closely read in silent isolation; for a time, it was a social practice, in the home and on the streets.

As Selma's life spirals further and further into visual and situational darkness, these dreams offer her a cruel respite from the world. In contrast with her bleak life, the song and dance numbers are explicitly brightened in the film. In one song, "I've Seen It All," Selma's inability to see has just been caught by her coworker as a train passes by, and as he proposes all the great things she will never see, she insists she does not care and that there is no more to see. She imagines the loggers on the train singing,

You've seen it all and all you have seen

You can always review on your own little screen

Selma, critically, was not always blind, and has built up a store of images to last her through the rest of her life. Selma's twelve year-old son, however, has not been blessed with so much time, and a central tension in the film concerns the fact that he may also soon lose his sight.

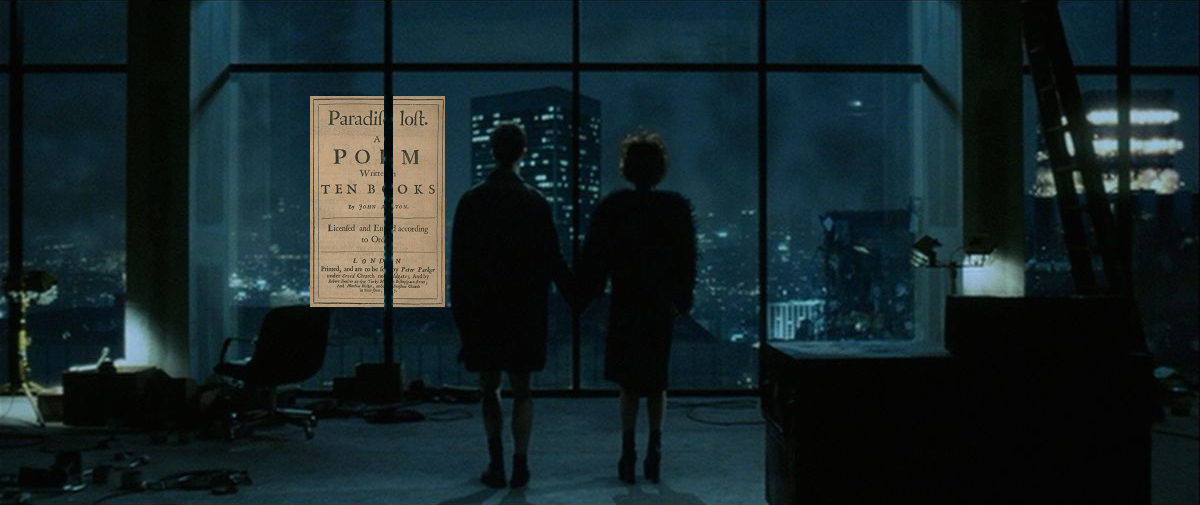

In "Sonnet 19" (1673), the poet John Milton questions, "Doth God exact day labour, light deny'd." Referencing the words of Jesus in the Book of Matthew, Milton suggests "they serve him best" "who best / Bear his milde yoak." Though he ends with a line about only standing and waiting, he remains troubled by wasting his talent. Four years later, he publishes his great epic, Paradise Lost. In his opening appeal to the muse, he pleads, "What in me is dark / Illumine."

Paradise Lost truly was inspired, but we don't have to read it anymore. We have the technology. Even audio can be a bit risky, though. Perhaps it is best if we only stand and wait. If you've found this post, you've probably read before, so you can just review that internally.

Escaping the Prison

Note that once you learn to read, you are then forced to read words that you see. As @fillegrossiere wrote on Twitter, "literacy is a prison."

literacy is a prison. once u learn to read u can’t just stop doing it. if u see words ur gonna read them. i hate that. oppressive

— SadeVEVO (@fillegrossiere) November 15, 2020

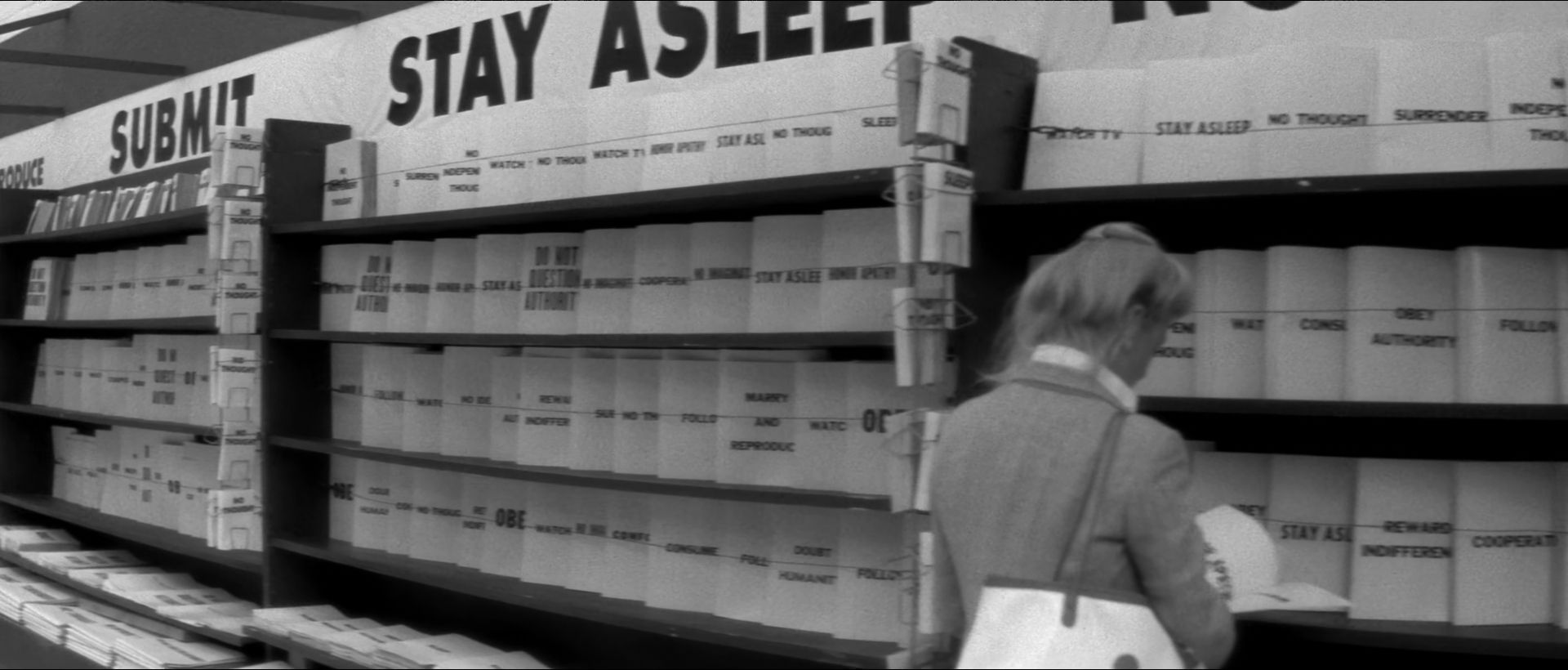

But do we truly understand the words that we see? Don't we need to learn critical reading skills, so that we might make sense of what is effecting us on deeper rhetorical levels? Consider the film They Live.

A man steals a pair of sunglasses from a church. When he looks through them, his usual colorful world of images, brands, and marketing slogans is replaced by a black-and-white world of simple messages. Almost everything is shown to be propaganda designed to foster a subservient life of no independent thought, per the needs of the masses of aliens who surround him in disguise.

The difference between his normal experience of the world and what he sees through the sunglasses is so stark that it would be impossible to properly explain his new perception to someone who has only ever had his old perspective. To solve this, he tries to get a friend to put on the glasses, but the man resists, and the two fight.

As the philosopher Slavoj Žižek frames the scene in his documentary The Pervert's Guide to Cinema, the glasses function like a critique of ideology, allowing you to see the real message. He suggests that we tend to imagine ideology as something like glasses placed over our normal view of society, and that through critique, we take those glasses off; to the contrary, he says, ideology is our spontaneous reaction, and we must be forced out of it.

In this view, materials such as books and magazine can be part of an ideological program which forms our spontaneous perception of the world. These inheritances are so pervasive, however, that they cannot simply be ignored. We need to go through the painful process of putting on the glasses – reading and thinking critically – in order to see through the illusion.

The reading and writing methods which govern our information society thus must be countered through more careful reading and writing. Instead of attempting to scale this challenging educational task society-wide, we could pursue an equally ambitious task: Reverse not just the information revolution, but mass literacy.

What are kids going to do? Just learn to read? It is their fate to never read.

Around the Web

- I have recommended this before, but I cannot fail to recommend Michael Sacasas' The Convivial Society here, given the relevance of Ivan Illich.

- I also highlighted E. L. Brooks before, but I recently spoke with him about Yvor Winters' poetry and the film Easy Rider, and Brooks coupled the discussion with public previews of three chapters of his upcoming book, The Loser, the Robot, and the Antichrist.

- existentialpervert69 wrote recently in a great newsletter about how the stories of our heroes select for a kind of meaning we often ignore in thinking about our "life's purpose."

- Molly Mielke just put together an extensive, well researched account of computers and creativity, which is well presented and worth checking out.

- If you have been successfully radicalized against reading, ignore the four texts linked above, and watch Michael Curzi demonstrate phenomenology through drawing his hand. As he notes, the information is already in his hand.

This post was first sent out as my monthly newsletter. To get this sort of insight each month (but usually about three works of literature), subscribe below: