Can literature exist on Instagram?

PreCursor Monthly – December 2020

Having earned a Ph.D. in English and taught poetry courses, there is no question raised so frequently as some variation of:

- Can literature exist on Instagram?

- Is Instagram poetry real literature?

- What do you think of Rupi Kaur?

This has never once been asked of me by a fan of such work, though seemingly there are many. Always, the implicit ask is, "Can you articulate better why exactly I am justified in disliking this?"

(Have a different question? Feel free to ask me anything about literature here. I will respond to anything to which I can reasonably speak. If the question is complicated enough and interesting enough, as with the questions above, I may follow-up with a more long-form post such as this.)

The Poetics of Instagram

The question as framed to me, "Can literature exist on Instagram?" is interesting. The short version of my initial draft is that even if you do not consider anything currently on Instagram to be "literature," it seems to me obviously true that a literary text (such a poem) can be posted onto there, and an original work could even make necessary use of some of the platform's defining features.

Some might find the hypothetical text to be of poor quality, or think that the use of the platform is more a detriment than offering any worthwhile dynamics between structural parts, but this is all hypothetical.

No one thought to make Lyrical Ballads until Wordsworth and Coleridge made Lyrical Ballads in 1798, so do not take your distaste for Alexander Pope as proof that poetry is over.

On the title page of the second edition of Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth warns followers of Pope – in a phrase distinctly at odds with the "real language of men" he is to champion in his Preface, and so directed out to that other audience – that the following poems will hardly be to their liking. He sets out to "create the taste by which he is to be relished" (as he explains in a later letter).

Perhaps Instagram does not inspire you. Perhaps you would prefer to work with Twitter or Roam Research, or any number of other platforms, or even create your own. The online world is powered by text, and if you find the literary potential in that so far squandered, you have an opportunity then to write your Lyrical Ballads.

What is it that the platform offers?

Early on, Instagram specialized in providing easy photo filters and a place to share those filtered photographs. (Filters now can be much more complex and serve different purposes.) At a time when phone cameras were still typically bad, filters were a quick way to make anyone something of an amateur photographer. As it became more viable to take decent-looking photos without the filters, users started skipping that step and advertising the fact: "#NoFilter."

In contrast to this active avoidance of the features presented for easy use by the masses, the Electronic Literature Organization just announced, as one of two winners for its 2020 Emerging Spaces for E-Lit Creations initiative, the Instagram Collaboratory Filter, from Sarah Whitcomb Laiola and Caleb Andrew Milligan. As those senior editors describe,

We embrace the creative and critical opportunities latent in specific features of Instagram; Stories, Boomerangs, Reposts, interactive stickers, 10-frame images posts, and short videos all offer opportunities to expand possibilities for e-literary creation and criticism. Filter’s mission is to support the circulation and promotion of works of e-lit that are optimized for, engage with, and/or disrupt the poetics of that platform.

Each of these types of content is a distinct potential form of creative work, and each includes multiple parts to how it is composed and the means by which it is seen.

People are already using these

In each previous newsletter, I have touched on at least one work of electronic literature, so if you have been following along, you have seen instances of this medium. Below, I look at Shelley Jackson's Snow. Broadly speaking, electronic literature makes some use of computer or network technology to literary effect.

In "Third Generation Electronic Literature," Leonardo Flores argues for understanding the medium as grouped into three generations:

- 1st (1952-1995): A small group of practitioners writing for a niche group of readers, as the category of people who had the means to access electronic literature was inherently limited.

- 2nd (post-commercial World Wide Web): Reaching a wider audience, an also wider range of practitioners is able to distribute works made in Flash, HTML, JavaScript, Python, Ruby, etc.

- 3rd (post-Web): Among such events as the surging smartphone market, more people are active online, with more sustained engagement. Ready-made creation and audience spaces such as social media platforms guide a massive proliferation of born-digital writing.

That last generation can include some works distinctly designed as creative projects, such as Twitterbots or the netprov Being @SpencerPratt. Flores, however, tries to open the electronic literature space more widely:

Even when they are not self-consciously producing literature-- societal concepts of literature are still dominated by the genres and modes developed in the print world-- a huge amount of people have used these tools to produce writing that has stepped away from the page to cross over into electronic literature territory, and it's a crucial move. Whether they know it or not, they are producing third generation electronic literature.

This is not to say that every post on any social media platform should be taken seriously as a literary work of art. It is worth considering, though, that literary practices and narrative sensibilities inherited directly or indirectly, consciously or unconsciously from literary history do inevitably shape people's capacity for producing in these mediums. Flores' point, though, is simply a critically necessary openness to the literary potential of such mediums, so that when interesting work does come out of these contexts, we "are able to recognize it as electronic literature."

Story in Progress, Platform Permitting

Shelley Jackson is most famous within electronic literature for her 1995 hypertext fiction Patchwork Girl, which draws on the Romantic novel Frankenstein and the non-linear structure of hypertext to pursue the complex reality of the body as a structuring narrative force.

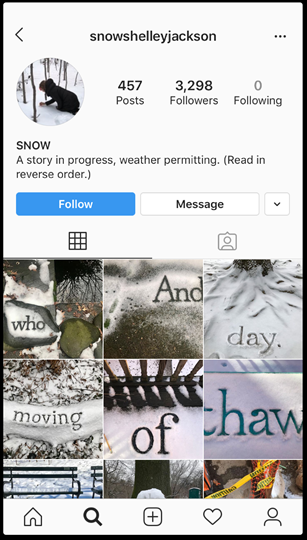

Snow, launched in 2014, is an ongoing story told on Instagram. Utilizing the platform's role as a photo-sharing app, each post is a unique encounter with snow, into each of which Jackson writes one single word.

Snow by Shelley Jackson as seen on a mobile display.

The first image here depicts the top of the page, and the last depicts the end. The middle depicts how the individual posts would appear within the platform's content feed. As the bio notes, you must read in reverse order, as the story starts with the account's first post. Accordingly, the story goes:

"To approach snow too closely is to forget what it ... thaw of moving day. And who ...

When it next snows near Jackson, the story will presumably continue. The latest post is currently from January 20, 2020, adding in the 456th word.

As the bio states, this is a "A story in progress, weather permitting." A year with less snow nearby means the story will progress slower, and so there is a climate element built-in. Note that Jackson keeps up with standard use of the platform and does not try to force the story.

She could easily, for instance, go out into a big snowy field and write the whole story out in a single day, posting photos of each word in quick succession. The first five words were all released January 22, 2014, presumably all taken in the same park. Once the story was established, more recent updates only add in one or two images / words, something of a normal post frequency.

Some things Jackson does not do: filters, multi-image posts, stories, videos, captions, hashtags, and various other formal and social affordances of the platform. This is not exhaustive of Instagram, but it does make distinct use of it and the general aesthetic sensibilities of its userbase. Snow will not be to everyone's taste, but this other instance of infinite possibility is worth considering with regards to the question, "Can literature exist on Instagram?"

As Flores notes, the benefit of such a work is that it is going directly to an audience (Snow currently has 3,261 followers). There is writing to be done with the story and considerations to be made with the photographs, but the distribution is a mass-market system designed for ease of use. Working with ready-made platforms, however, means being subject to any shifts in design or audience on those platforms.

The work is not just weather permitting, but platform permitting. If Instagram for some reason decided to reorganize accounts not chronologically, but by number of likes, for instance, Jackson would suddenly have a radically different (probably incoherent) story. Would you want to then reconstruct it into its imagined correct form as chronological, or try to grapple with it as given (perhaps even nudge certain posts into different places via liking)? Those sorts of considerations are a core overlap between the study of electronic literature and our more general understanding of real-world platform use.

(For a much more thorough consideration of Snow in the context of Kaur and Instagram, check out Kathi Inman Berens' essay "E-Lit's #1 Hit: Is Instagram Poetry E-literature?")

Home Body Once Told Me

Reinventing the Instagram wall would not only interrupt Jackson's narrative flow, it would also disrupt design best practices.

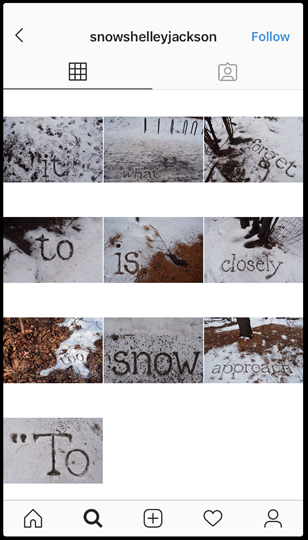

Rupi Kaur uses a strategic posting strategy that alternates consistently between one photograph and one image of black text (and frequently, simple black doodles) on a white background. The effect is this constant grid which looks nice, makes each post stick out, and frames the simply-designed poetry posts.

Kaur is the biggest Instagram poet, and declared "Writer of the Decade" last December by Rumaan Alam in The New Republic. Her third book of poems, Home Body, came out November 17, 2020, and its release is the occasion for the upsurge in questions about her and Instagram's literary potential more broadly that has inspired this post.

Her success is pure business. If you are worried about the fate of poetry, don't. No one is reading Kaur and then throwing away their copies of some other major poet, contemporary or classic.

No one is standing in a bookstore holding Home Body in one hand and My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree in the other, debating between them in a sweat.

In the current marketplace, technical categorization, such as of "poetry," is critical. One of the key things Kaur has accomplished is taking the content of a massively popular genre (self-help) and adapting it to appear as one of the lowest-selling genres (poetry). Though helped by her existing social media influence, the result of this move is that the book easily becomes the #1 selling book in Poetry on Amazon, bringing the sale numbers of the whole genre up.

Kaur's impact on sales charts is mistaken – intentionally as a marketing move by her team and out of anxiety by her critics – as some form of artistic success. It is, instead, a very cynical move. She gets to be advertised then as the #1 poet, and such success is then self-replicating.

Why sell poetry

The category of poetry also has cultural value, as does a well-designed print book. The basic concept of virality, as on Instagram, is that people interact with and share that which is relatable. The simpler and more broadly appealing you can make something, the more easily it can reach many people as readers will see something and think of someone (or a group) with which to share. Within such social distribution, addressing tough subjects (as Kaur does) through concise shareable media creates a level of remove which makes expression easier than directly stating difficult truths in an earnest way.

Such concise shareable media, however, typically comes through meme culture, which can often adapt from existing media, such as Shrek. One poem in Home Body reads (along with a drawing of two hands, palms open, holding up flower with a huge bulb and sprawling roots):

i'm done trying to

prove myself

to myself

On Facebook, similar messages go viral everyday, but with images of Minions attached or things of that nature. Among frequent ironic detachment through low culture frames, the façade of poetry can offer some a refreshing offer of legitimacy to certain thoughts and feelings. Seeing those poems as a professionally published book gives further reinforcement and so it feels good to own a cultural object which gives at least the illusion of serious artistic value for personal matters ranging from the banal to the deeply traumatic.

There is skill to recognizing popular feelings and capturing them in a concise way. There is especially skill to being able to pull it off consistently over years. Combined with extensive literary skills and ambitions, you can use such insight to create really profound work. In itself, though, in this current context, this skill is just marketing.

Fellow Instagram poet Robert Macias was a professional in digital communication, creating campaigns for brands such as McDonald's and Kellogg's, who then quit to apply his skill-set to crafting his own brand, r. m. drake. Maybe someone can show me a good poem by him, but you are at least as likely to show me one by someone with less than 1% as many followers. Kaur never sold people on Big Macs, but has the same sort of educational background and has spoken in interviews about browsing the surrounding publishing world not as sources of literary inspiration, but references of successful design.

Their work is shallow and poorly written – what in poetry is called doggerel – but they are clearly very successful marketers. I have seen many attempts at parody, but no one can quite pull it off for even a few poems in a row, much less as a consistent six-year brand which is still going strong.

Can literature exist on Instagram?

Whether trying to build an audience for more traditional writing or trying to make explicit use of the platform's many features, there is no reason you can't use Instagram to host and share literature. It does not innately support long-form writing very well (which Jackson's Snow pushes against), but like with a sonnet, for instance, constraints can be highly productive.

As I suggested above, if you think writing within the constraints of Instagram can be done better – perhaps even way better – take up that challenge yourself. Then reach out to Sarah Witcomb Laiola and Caleb Andrew Milligan about Filter. The electronic literature community has space (but not necessarily riches) for you.

Mass Writing and Niche Writing

The idea of generations of electronic literature indicates major shifts. It does not mean that you have to write in newer modes. The sort of highly experimental writing made for niche audiences, offered by the first generation, is still possible and still has its merits.

Consider the case of William Blake, who died in 1827, but who I was born just in time to read.

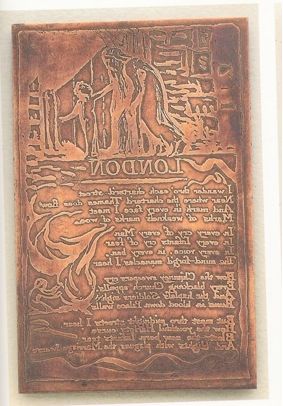

Blake did not make mass published books like his contemporaries. He made copper plates, then etched out and colored small numbers of copies of his works. You would go directly to him to get one.

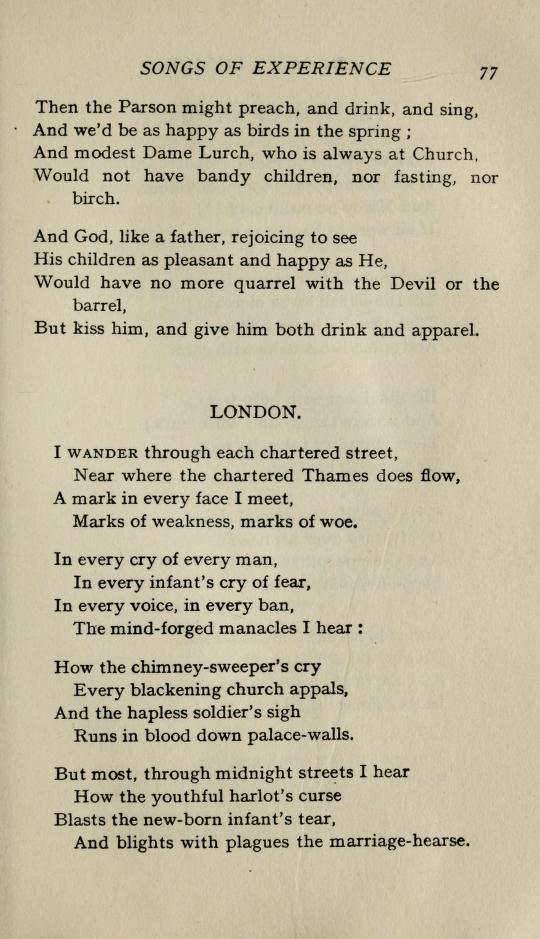

Most people who have read Blake have not seen those engravings directly. They have seen some form of edited collection of his writing and/or art. In the case of a 1905 collection edited by fellow poet W. B. Yeats, the poems were presented as all text:

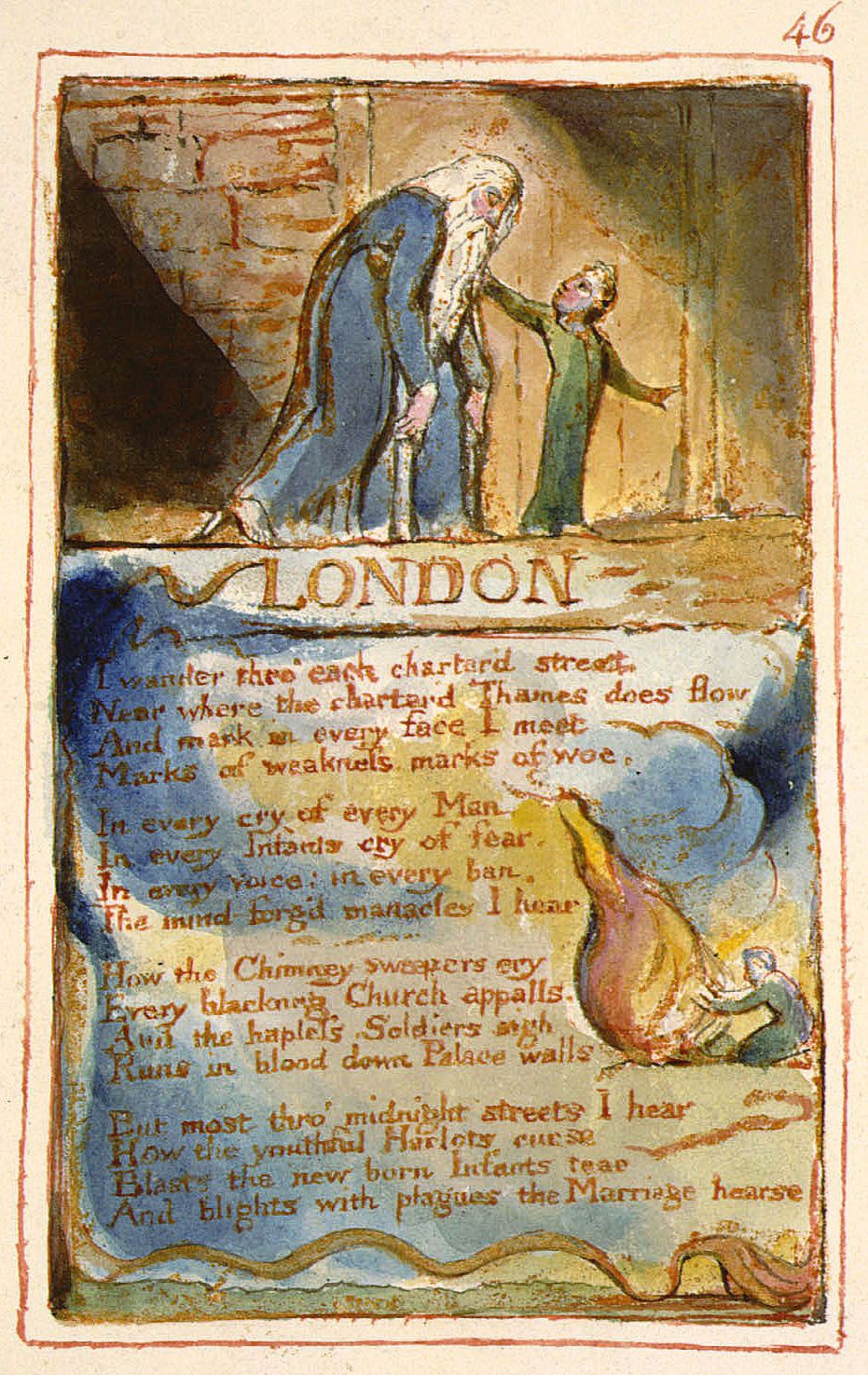

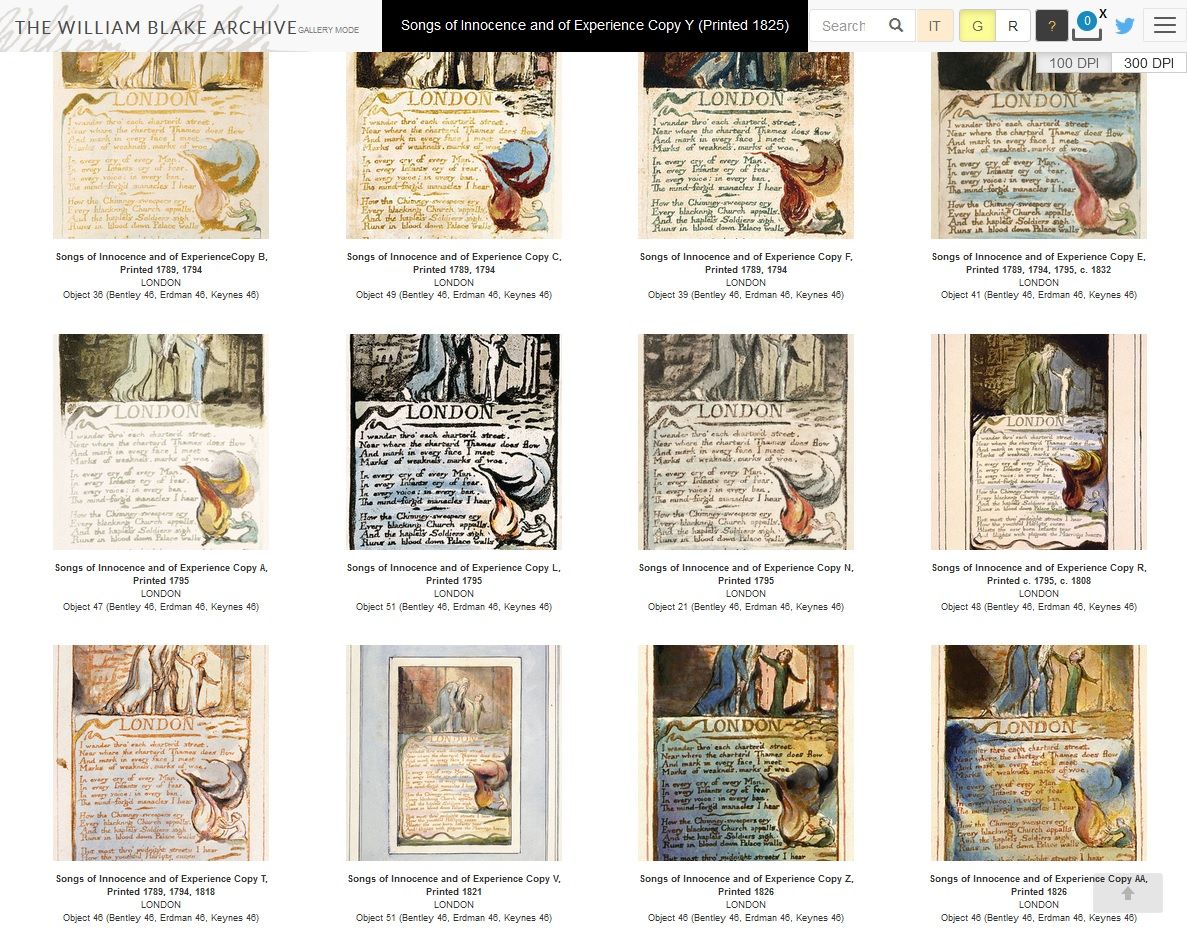

In printing and reading Blake with illustrations, practical matters require that you select what illustrations to include. Looking at the online William Blake Archive, however, which we now have, we can see this selection of just this one page:

Different copies, worked on at different points across multiple decades, frame the poem differently. He writes,

I wander thro' each charter'd street,

Near where the charter'd Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

There is more to the work, however, than this. In 1991, Jerome McGann argued in The Textual Condition that we need to consider not just words to interpret but textuality as a process of producing material objects (books, prints, magazines, etc.), and that the full context of the page Blake produces cannot be ignored.

The William Blake Archive launched several years later, and is an ongoing project. This resource now means anyone with a networked computer can read the actual breadth of Blake's poetic output, without traveling around the world to various physical archives.

This new possibility is not necessarily a neutral one, though. N. Katherine Hayles suggests in My Mother Was a Computer,

In terms of the William Blake Archive, we might reasonably ask: if slight color variations affect meaning, how much more does the reader's navigation of the complex functionalities of this site affect what the texts signify?

The archive enables new readings of Blake. It is more comprehensive than Blake himself could have anticipated, but arguably for the better, and various decisions big and small on the site shape what exactly that new reading looks like. It is a great case study of

- How might you write highly idiosyncratic works outside of standard writing practices?

- How might you adapt such works to a unified online system?

In that way, it also suggests some ways we might now approach original writing for the screen. We were born just in time for this.

As readers and/or writers, do not stress the experiments and commercial practices you do not like. Focus on what you do like and the vast potentials awaiting us. This is a very good time to be deeply interested in literature.

Around the Web

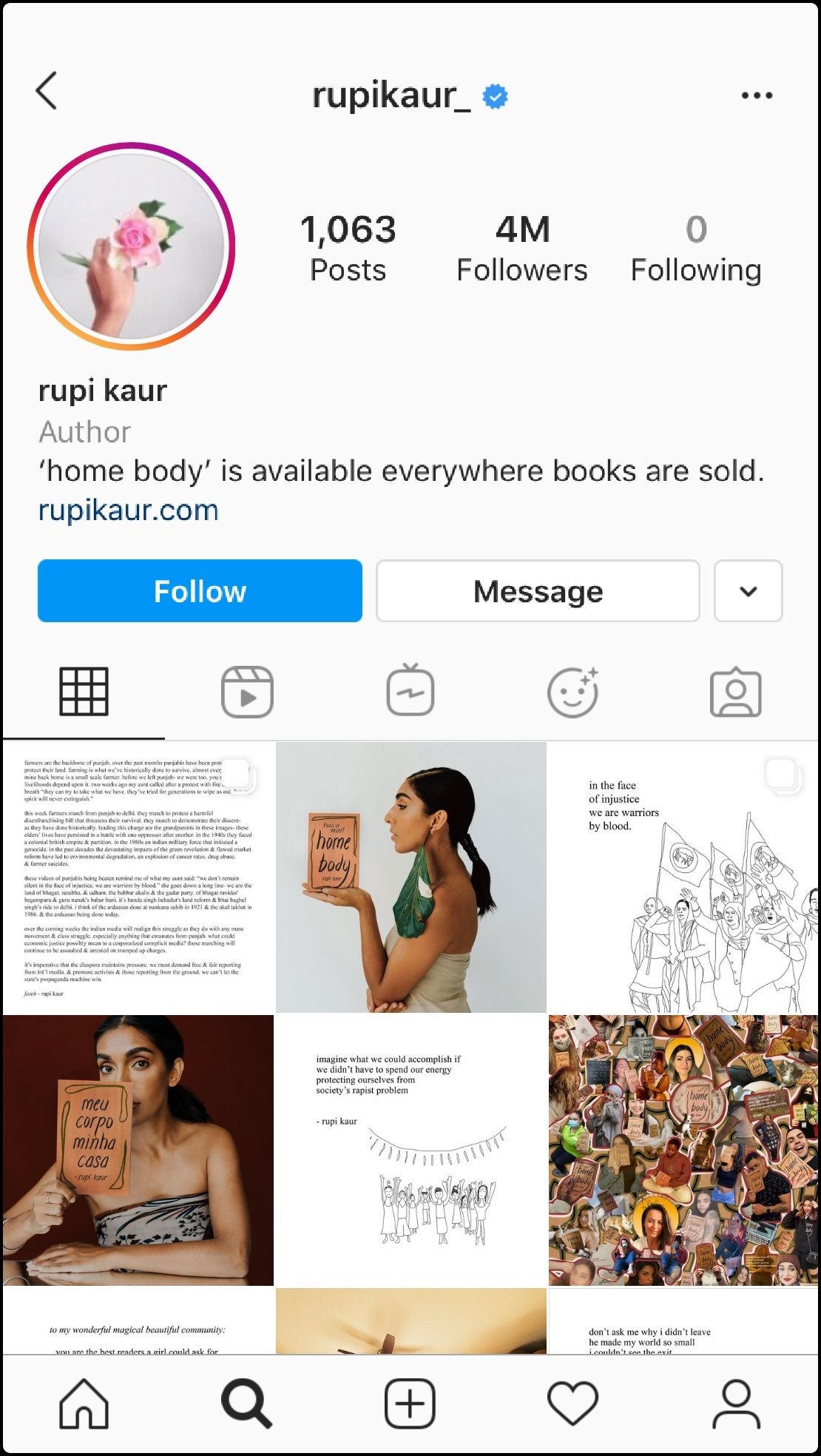

- The Future of Text was just published as a free book (in PDF and EPUB). Edited by Frode Hegland, the book collects a massive amount of short (1-3 page) comments from contributors across fields on the titular subject.

- A writer going by the name Dikaiopolis 2 is currently working on a novel-in-graph, run through the existing platform Roam Research. You can read his theoretical intro and sign-up to get access to the work-in-progress here and listen to my interview with him here.

- You can read more about William Blake through the newly-released Issue 1 of Vala, the journal of The Blake Society.

- You can revisit Ralph Waldo Emerson through the first entry of ex.haust's "American Canon" series, addressing what "Self-Reliance" has to offer us today.

- I was just joined by Jeremy Fox, LPC for the first in a weekly series of podcasts exploring moments of synchronicity between one literary work and one film released in close proximity. This first episode brings together "Shakespeare's Memory," one of the last stories of Jorge Luis Borges, with David Cronenberg's Videodrome. Jeremy Fox brought in a lot of interesting perspectives from the psychology world, particularly around trauma, so please consider checking that out (YouTube, Podbean, Apple, Spotify).

This post was distributed first via email as my monthly newsletter. Each month I bring new literature, classic literature, and electronic literature together in conversation. If you would like to receive future editions in your inbox, sign up for free below: