Choose Your Own Memory

Five years have past; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters!

— William Wordsworth, "Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting the Banks of the Wye during a Tour. July 13, 1798"

In William Wordsworth's "The Ruined Cottage," we saw how simple language could convey the intense history of feeling present in a place. With the cottage itself in ruins and the holder of the story as well nearing the end of his life, Wordsworth's speaker saw an irresistible value, wanting to extract as much of the tale as he could.

Though Wordsworth elsewhere situated himself as a prophet of Nature, he was not content to see nature overtake this dwelling and this life. The value in the place, for him, was precisely in that human history, that way of seeing something more within those "naked walls."

The old man as well, in telling his story, finds the tale not just something of interesting, but a continual presence in both his mind and the physical scene:

’Tis long and tedious, but my spirit clings

To that poor woman: so familiarly

Do I perceive her manner, and her look

And presence, and so deeply do I feel

Her goodness, that not seldom in my walks

A momentary trance comes over me;

And to myself I seem to muse on one

By sorrow laid asleep or borne away,

A human being destined to awake

To human life, or something very near

To human life, when he shall come again

For whom she suffered.

This naturally-occurring "trance" state Wordsworth tries to recapture in his poetry. In his preface to the second edition of Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth wrote,

poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility … the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquility gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind.

The poem, therefore, is not located in the original experience nor is it trying to be a mimetic copy of it. In the tranquil reflection, however, the poet is able, ideally, to capture the process of remembering so clearly that a new instance of the original type of emotion is actively produced by this new virtual encounter.

As Wordsworth approaches this in his poetry, it is not just memory, but a sort of return. In "Tintern Abbey," he writes "I cannot paint / What then I was" – and so instead tries to revive the feeling and, in particular here, place it onto his sister. We can see a version of this now in a certain type of retro media aesthetics:

and as brian eno pointed out, once a limitation is transcended, it will be romanticized. you see kids on tiktoks and fancams etc doing this right now with artificially grainy fancams meant to look like VCR footage pic.twitter.com/z0UsYhxf91

— visa is almost done ✍🏾📖 (@visakanv) April 29, 2021

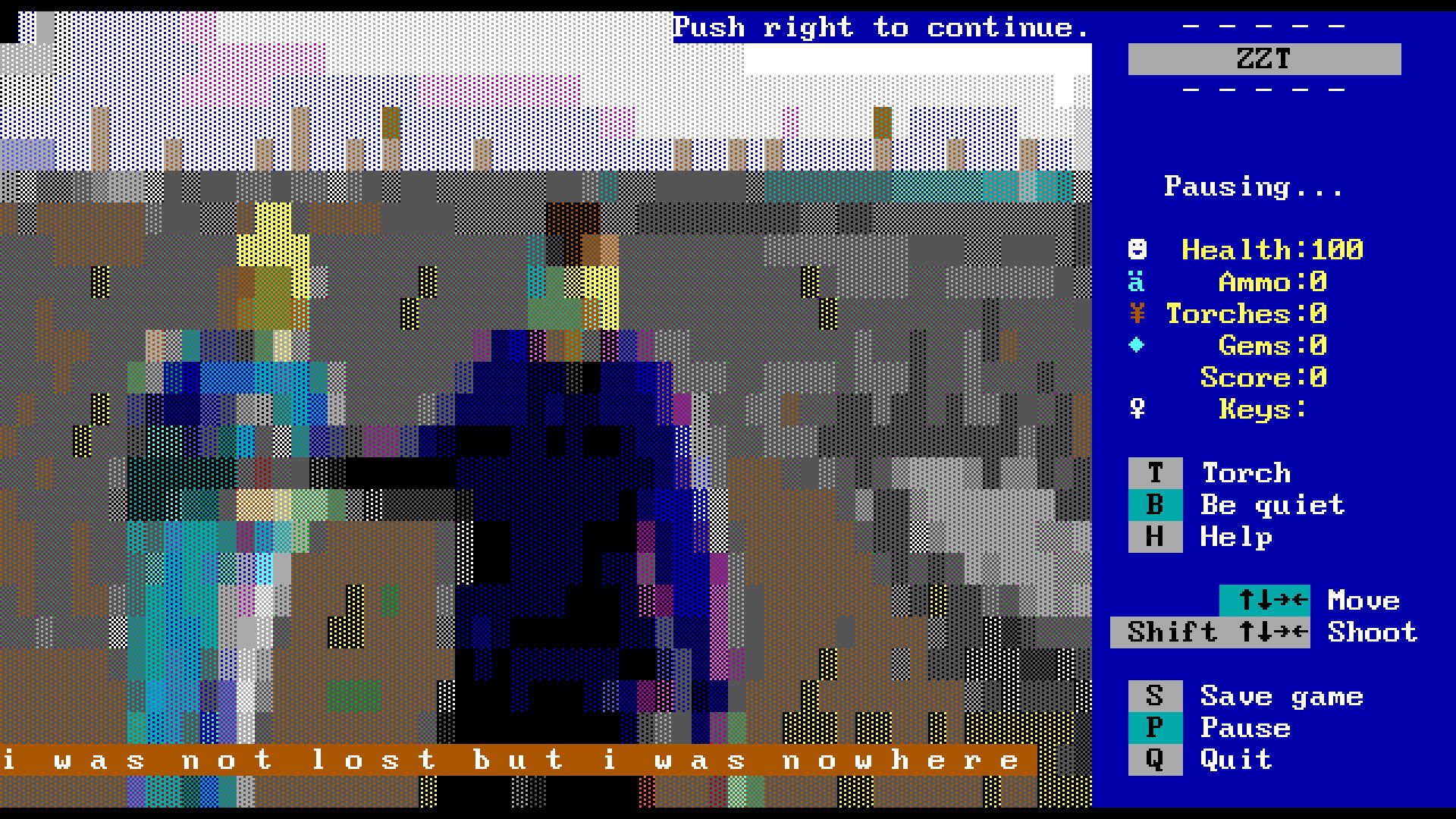

Something reminiscent to the Wordsworth naturally emerges when you have a revival of interest in the shareware use of ZZT – a 1991 game by Tim Sweeney – as a foundation to make your own games.

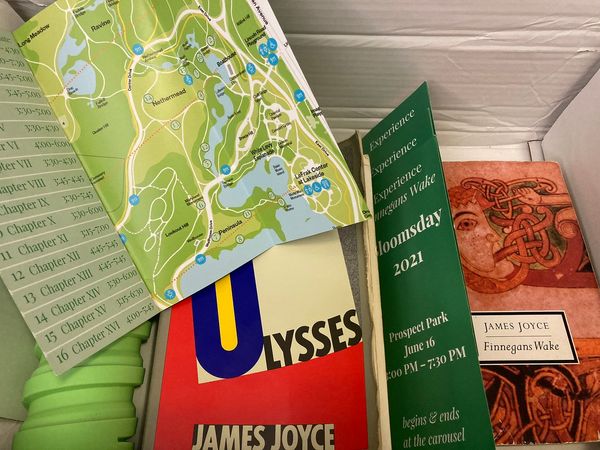

We find this in Jeremy W. Kaufmann's When There Is No More Snow. As he notes in a section of bonus material, the last ZZT game he made was in 1996. Rather than Wordsworth's five-year-delayed return, Kaufmann is coming back to these ruins after twenty-five years – but he is not just returning to the (reconstructed) program; the story he tells is a semi-autobiographic tale of youth.

Though the older visual style of the program is presumably not how Kaufmann sees his own memories, it is part of them, in a way which can be shared with a larger audience. Even for those who did not play around with ZZT specifically, the above visuals are likely to instantly transport any reader into roughly the right era.

The story is told through simple navigation (to the right), with occasional choices, which offer some branching options. Each run is fairly quick, but can end in several ways, some I found harder to navigate to than others. The short of it is: You are living with your father and your sister; you are poor with little to eat; you need to decide how to balance your time between your father, your sister, your mother, and your friends.

In a few particularly emotional scenes, the text explodes outward:

If you argue with your dad instead of practicing on your saxophone, you can take the dog on a long walk. There, the more chaotic image above is followed by a simpler image of a lake. This natural scene frames – both personally and visual-narratively – the inner events:

me and dog walk down to cat lake. it takes more than an hour, but i am still going through the cycle of angry, then sad, then numb, and finally, calm. we walk on.

This emotional cycle repeats as the overarching narrative of the game. You spend a few minutes playing through one route, then start over and do something else. The interactive nature of such contemporary narratives makes the emotional payoff more variable than "The Ruined Cottage," but achieves something new through the process of that variance.

The first choice you are given is to make food for your sister or get angry with her. What all is opened or closed in these decisions? In looking back at the ruins of the past, things might have gone so different. Under the right set of circumstances, you might have been abducted by aliens. Who knows?

In the bonus materials, we are given a travelogue: a recent train ride with Kaufmann and his girlfriend as he finished up When There Is No More Snow. This part is non-interactive, but full of choices – a place to be opened up, whether in five years or twenty-five. The ruins which might frame that future narrative do not yet exist as such, but they're there in what we half-perceive and half-create.

If you would like to see more conversations between literature old and new, electronic and print, subscribe below to my monthly newsletter.