Galatea, pt. 3

PreCursor Monthly — October 2020

The deep learning language model GPT-3 launched back in June. GPT-3 stands for "Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3," but in seeing some people get highly invested into interactions with it, I thought it is also a bit of a Galatea, or a Galatea pt. 3, if you will.

In Greek myth, Galatea was a statue carved by Pygmalion which then came to life. In Ovid's long poetic narrative Metamorphoses, Galatea is brought to life by Aphrodite in response to prayers by Pygmalion who then marries Galatea, though the core myth does not strictly require this dynamic. At its core, you have the artistic creation of a beautiful woman, masterfully formed from ivory, and then what happens when this idealized form is given life.

What can an artist do here but fall madly in love with his creation, which is both his ideal other and also, in some ways, an outpouring of himself?

Frankenstein is a horrific reversal of this expectation, as Victor Frankenstein, in forming his creation, "had selected his features as beautiful." Only once the creature is given life is Victor snapped out of his delusions of the greatness of his work and sees, among other things, that "His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath." He is horrified and flees, another situation brilliantly adapted by James Whale in his 1935 film The Bride of Frankenstein. Whereas in the novel, the proposed mate for the creature is only an ideal and never given life, this film imagines that the creature is given his bride and she is, as was Victor, horrified, and screams.

Once an ideal is alive, it may not give back our ideal response.

Galatea, pt. 1

Translating the myth into robotic terms offers an opportunity to remove some autonomy from Galatea. No longer animated by some mysterious soul or other force, but mere mechanics, a robot will typically be constrained to its creator's or owner's will. This is now troubling in a new way.

Emily Short's Galatea complicates things in an interesting way.

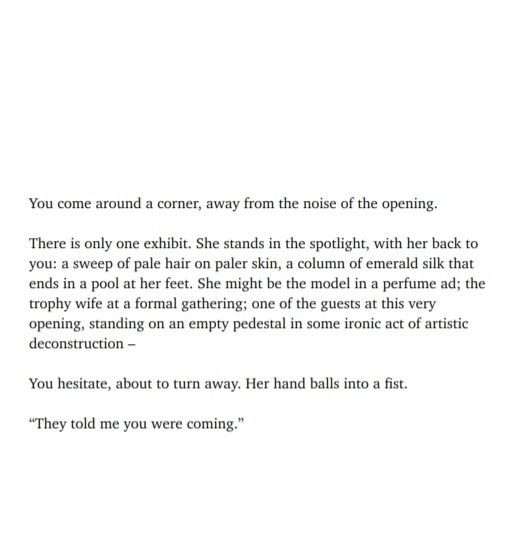

A 2000 interactive fiction work, Galatea removes traditional movement and action abilities, focusing instead on social interactions in line with earlier chatterbots. What makes Short's work distinct is that her work is an involved story (or, perhaps more accurately, stories) which allows readers to work through the conversation and interaction (as you can look, touch, smell, even kiss if you can make it happen). Her Galatea has a personality and history. There are things she does not know, which you can tell her, and she has much she can tell you. Much content can only come up when worked up to through a conversation that steadily opens up information back-and-forth, and Galatea has shifting moods which guide options as well.

No longer just a story about Galatea, or a story about Pygmalion featuring Galatea. Here Galatea is the star and if you want her story, you need to learn how to work your way through the text's many parts. In the opening screen, "She stands in the spotlight, with her back to you." Because the game lacks movement abilities, you cannot simply walk around her so that you are face to face. You talk to her over her shoulder, and in time can learn how to get her to turn around and speak to you more directly.

Galatea (Emily Short)

The opening screen also notes that this is an "exhibit," but unlike the traditional sculptor myth might imply, and contrary to what Galatea here herself assumes, this is not an art exhibit. It is an artificial intelligence exhibit, showing off different experiments in embodied AIs, here called animates. Short thus engages with the context of computerized Galateas (which the work itself as software necessarily concerns), but ultimately maintains significant mystery around this Galatea. As player-character, you can question and inspect her, and find that she appears not to be a normal mechanical animate. Accordingly, while one of the other artists leads his creation around as his pretend date, Galatea is free to do much more and can even be a genuine (potentially fatal) threat to the player.

The one key frustration is that you really do need to learn how to talk to Galatea, in sometimes quite limited ways. Most things you try will not work. The program will simply not have a way to proceed from your input. This, however, allows the expertly curated stories we have.

A remarkable thing about electronic literature is that while technology improves significantly, these early works – as artistic creations – remain impressive achievements in the medium. You might assume that between 2000 and now, you would have played with way better chatterbots, yet Galatea still stands out.

Galatea, pt. 2

Like this next text, we are not proceeding within a strict chronological metaphor of improvement through future iterations. Rather, we are proceeding according to my narrative needs.

Back in 1995, Richard Powers' novel Galatea 2.2 is a prominent literary example of the sort of high tech context in which Short's Galatea emerges five years later. For a more recent example, you might consider the film Her (2013).

Galatea 2.2 follows a writer set to the task of training a neural net on the great books, with the goal of creating a system that could comment intelligibly on a graduate-level question about literature. Alternating with this in the novel, there is a parallel story, further back in time, of him falling in love with his by-then-ex-wife. An eventual realization, then, is that the literary knowledge is not enough to answer meaningfully. The machine also needs to know some non-fiction, "the books that books only imitated," some of which are the letters between his ex-wife and himself.

In the process of working with the neural net across multiple iterations, it is not just that he is training the machine. He finds that the machine is training him – to live, to think, to tell stories. He is already an established fiction writer, but losing his interest. The AI helps him understand (again) why it is he should make up fictions.

This is a decent book on its own, though perhaps a bit too caught up on its own themes (on love, on projection, on living for oneself and for another) to be quite the commentary on something like GPT-3 that this newsletter demands. What I can say here is that, in reading this novel, I was reminded how much what AI Dungeon – the text adventure system that is currently the main way the average person is currently able to play with (a limited form of) GPT-3 – excels at is specifically providing very story-like stories. The stories rarely make much real-world sense, and only achieve what they do with heavy user prodding (and so we, like Richard Powers' self-named protagonist, are the ones being trained).

The training as presented in the novel is interesting. It is rarely obvious what the system needs to know that it would not otherwise know, and so Powers must learn how to present information and questions to the AI. His year in training becomes something of a microcosm of the trial and error of his broader life.

Galatea, pt. 3

The hype surrounding the launch of GPT-3 was intense, eventually settling down into the acknowledgement that this would not yet revolutionize everything, but that we were starting to see some evidence that some later iteration would. As we saw with Short's Galatea, though, for the arts, text generation does not have to be perfect. Short, as a normal person, crafted the text's webs. What she made was extensive, but finite. GPT, accordingly, would not have to produce infinite high-quality material, just fast-track the creation of some high-quality material.

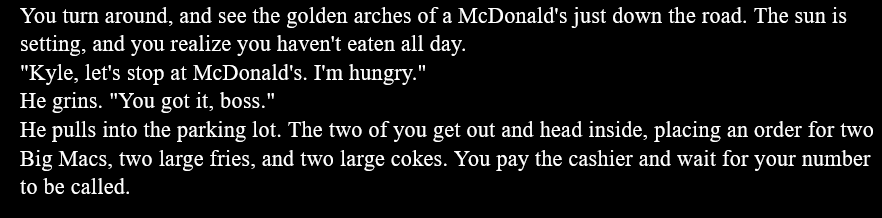

AI Dungeon is a text adventure game launched in 2019 on the GPT-2 model, then upgraded to allow use of GPT-3 in June 2020. The game system has a selection of established scenarios based around pre-set roles within the categories of Fantasy, Mystery, Apocalyptic, Zombies, or Cyberpunk.

Like Richard Powers feeding old books to the neural net, AI Dungeon draws on a corpus of existing stories. Free online texts such as from fanfiction writers is a major source of its writing, and sometimes elements of the websites rather than the stories will accidentally bleed through. Since Fantasy forms the largest part of its corpus, AI Dungeon recommends a fantasy setting, in which you can choose to be a noble, princess, knight, wizard, witch, ranger, squire, peasant, rogue, or fairy. Apocalyptic, by contrast, only allows you to be a soldier, survivor, or courier. You can also skip choosing a setting and character altogether and select "Custom," but the difference in options between Fantasy and Apocalyptic can give some sense of the game's ability to handle topics way off-track. These came up in an attempt to do Apocalyptic:

This starts lifting from a Joker fanfiction because we were in a McDonald's (connected by clowns), and we were in a McDonald's because we were traveling down a road. Forget the apocalypse. AI Dungeon still works mostly around taking the most immediate context and adapting, impressively, but not with the sort of coherence offered by something like Short's Galatea. Nevertheless, the surprise of seeing this trove of writing get remixed on the fly to fit whatever I command produces delight. It is a great extension of the idea of hypertext readers as writers.

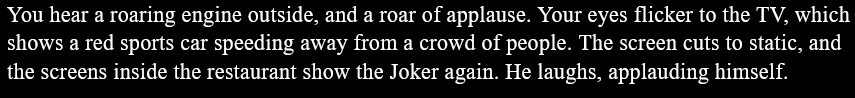

Below is the beginning and ending of my longest story attempt, starting as "patient" in the Mystery setting.

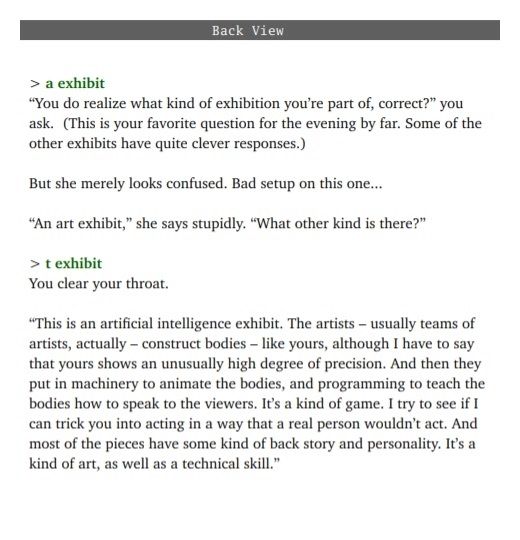

The paragraph at the top is a standard starting story, giving the quest, "Figure out who you are." You can then interact through a text box.

AI Dungeon allows you to use Do, Say, or more open-ended Story commands, the last of which allows you to simple fill in the next line or two. Classic interactive fictions were limited to strict lists of commands, such as "Ask" in Galatea, for commands such as "Ask Galatea about ocean." The freedom allowed in this current system is incredible, and, in the short-term, AI Dungeon's ability to parse most inputs and generate a reasonable response is remarkable.

Where the system falls short is that it only understands what is happening in a very limited sense, and it has a short memory. AI Dungeon allows you to pin important information, though you need to format that carefully in ways the system can understand simply and apply as it generates new text. Even this does not always work.

I commented earlier that this game provides "very story-like stories." What I mean is that they are not like life. They are like very weird stories, and if you can learn to embrace that weirdness and interact with the program in the ways it excels, you can end up with wonderful encounters, as pictured above.

Essentially, you are training the AI to buffer out the parts where it fails to entertain. The problem for this producing serious literature is

- The mechanisms of its learning inclines the AI toward forms of writing with mass appeal.

- Limiting a corpus to great books means you are drawing on a selection of writers with distinct styles. In Galatea 2.2, the project of teaching the AI great book starts with a challenge that the neural net could outdo a graduate student in English. One form of assessment is that the student should be able to identify the sources of great lines, such as from Milton or Shakespeare, and explain some of the writing's significance in context. The whole premise is that we can recognize Milton in particular. The AI, then, can either write in the style of existing authors and be a poor imitation, or blur them to try to create a new style, but will this be the same as a person's creative shaping of voice?

- If you want to buffer out the writing output to become high literature, you need it to be trained by a more narrow selection of people who appreciate high literature, and you need to be sure that they are only training it to suit their high literary sensibilities, even though many such readers also enjoy some mass market writing. Now, this requires an impossible parsing of one's literary sensibilities, while also not being too self-conscious in signalling to the AI as you read and interact.

Uncreating Galatea

One direction literature can go is the openly uncreative. This is the direction taken by Kenneth Goldsmith in his 2011 study Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age.

As Goldsmith recognizes, text abounds in our online world; however, most of it is not meaningful or overtly literary. At one point, he notes how in browsing news and social media and so on, we are seeing more text per day than ever before, even if we skip over or half-read most of it. Further, through understanding code as text, we can view other media (images, video, audio) also as text and play around with that material. More careful writers, then, can mine this trove of text and extract, reframe, edit, and so on to produce works which are less about a nicely readable output than they are about the construction of that text.

For wider literary context, Goldsmith looks back to writers such as Gertrude Stein:

Shutters shut and open so do queens. Shutters shut and shutters and so shutters shut and shutters and so and so shutters and so shutters shut and so shutters shut and shutters and so. And so shutters shut and so and also. And also and so and so and also.

Exact resemblance to exact resemblance the exact resemblance as exact resemblance, exactly as resembling, exactly resembling, exactly in resemblance exactly and resemblance. For this is so. Because.

Now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all.

Have hold and hear, actively repeat at all.

I judge judge.

Or James Joyce:

As we there are where are we are we there from tomtittot to teetootomtotalitarian. Tea tea too oo.

Whom will comes over. Who to caps ever. And howelse do we hook our hike to find that pint of porter place? Am shot, says the big-guard.

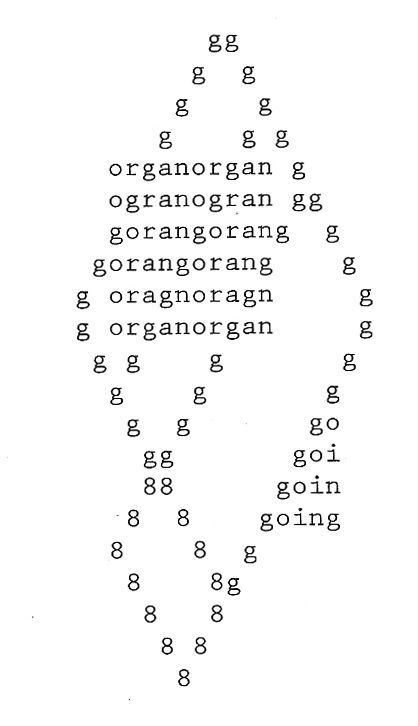

Or concrete poetry:

Goldsmith makes the point that concrete poetry had a moment in the 20th century, but without yet "an appropriate environment in which it could flourish" (62). His premise is that we now have this.

While others work on training GPT-3 and similar on literary corpora to produce quality literature, and related poetic experiments, perhaps we might instead (re)train ourselves to appreciate different (un)creative forms.

Must we craft Galatea as such an idealized object of desire? Or can we learn to interact with her as she is?

This was sent out as my October newsletter. I send out similar updates on new, electronic, and classic literature in conversation at the beginning of each month. To receive future updates directly in your inbox, sign up below: