Post-Contemporary Literature: 2020s and Beyond

Over the summer, I did a retrospective on some contemporary literature. In 10 posts over 10 weeks, I explored a sample of 2010s literature. The subject was "Literature and Hyperconnectivity" and what I was tracing primarily was

- How and why many writers have avoided depicting our hyperconnected contemporary reality in literature.

- Examples of different ways in which this steadily changed.

By now, though there are still many works coming out which are set in different historical periods or find ways to downplay or ignore digital technology, the fact of hyperconnectivity in literary narratives is now a normal occurrence. For just two examples coming out soon, consider Fake Accounts by Lauren Oyler and No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood.

That, however, is a matter of content. As I touched on in two of my ten "Literature and Hyperconnectivity" posts and once each month in my newsletter, a further way of engaging with our high-tech world through literature is through works which make some essential use of computer or networked technology, which is known as electronic literature.

I believe that a key year in the shift to literature about the digital age is 2013. I have twice taught a university course doing a case study of this year, which includes, among other notable releases, Thomas Pynchon's latest novel, Bleeding Edge (you can view me discussing some elements here and read other notes here).

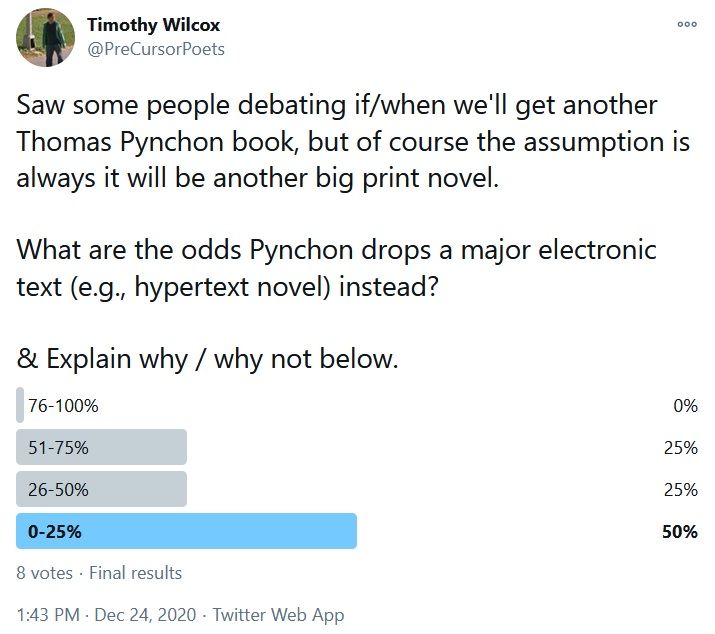

Given this work, when I recently saw some people discussing if/when we will get another Pynchon book, it stuck out to me that the assumption is that he would release another big print novel, instead of expanding out in other directions. I asked on Twitter what people thought were the odds that he might instead drop a substantial electronic text, such as a hypertext novel:

Half of those who voted thought it was very unlikely that Pynchon would write an electronic text. Two of the eight voters, however, thought it was more likely than not that he would.

For myself, I would say the odds of Pynchon specifically writing such a text is low. I would vote 26-50% odds. I am going to make a wider prediction, however:

The 2010s were where depicting the digital age in literature became mainstream. The 2020s will be where major authors make the jump to electronic.

With this idea in mind, I did a new series of five polls:

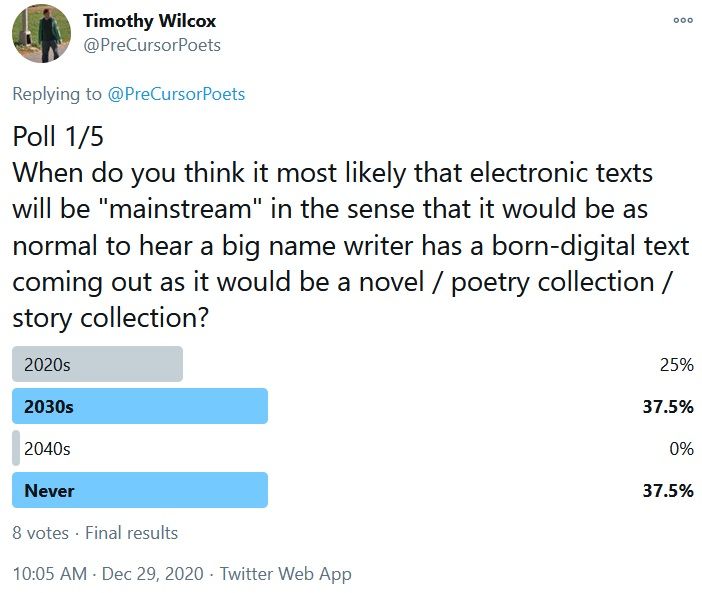

First, I wondered when others thought this jump might happen. When would it become mainstream – in the sense that it would be as normal to hear that a big name writer such as Pynchon has a born-digital text coming out as it would be that he has written a new print novel?

Of eight votes, the leading sense was split evenly between thinking it would be either in the 2030s or never. No one thought it would happen in the 2040s. After all, such works exist right now. There are many of them, in all sorts of lengths and styles. There is already a critical mass of screen-bound readers, but most are not reading electronic literature (though some definitions may trouble that claim). It seems unlikely that it would take so long for this sort of shift to occur.

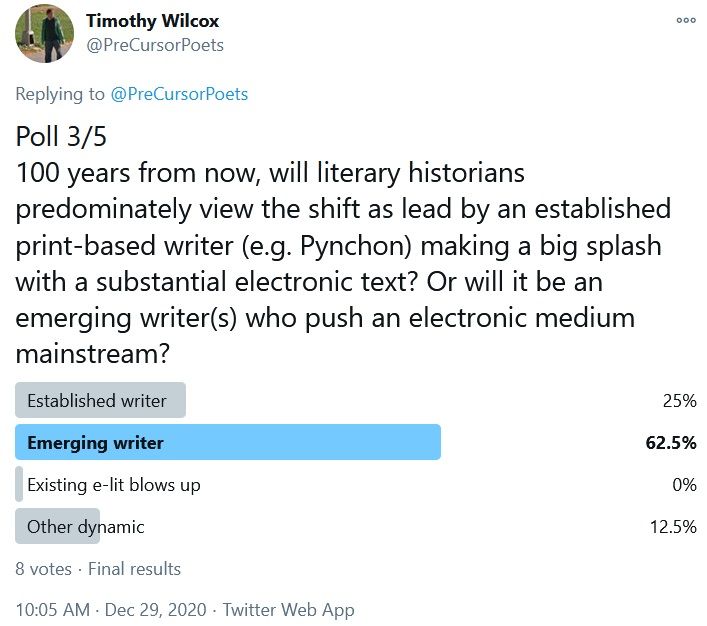

Jumping ahead to my third poll, I wondered if some work or works within the substantial history of existing electronic literature would jump out to wider readership – whether through new reading tools, expanded curation, a cultural shift, or some other means. None of the eight voters expect this to be the case.

Instead, the majority felt it would take a new emerging writer to popularize the form. Perhaps a new writer could determine a form or framing which would attract something like the tens of thousands who read Sally Rooney's 2018 novel Normal People, a substantial number for literary fiction.

While my earlier poll had several people expecting modest but not impossible odds that Thomas Pynchon would produce an electronic novel, only two now found it most likely that such an established writer would shift over and drive a substantial growth in electronic literature readership. It is worth considering that if Pynchon – or, say, Claudia Rankine in the poetry world – did make such a shift, it would almost necessitate a big readership following.

So what would the first thoroughly mainstream electronic texts look like?

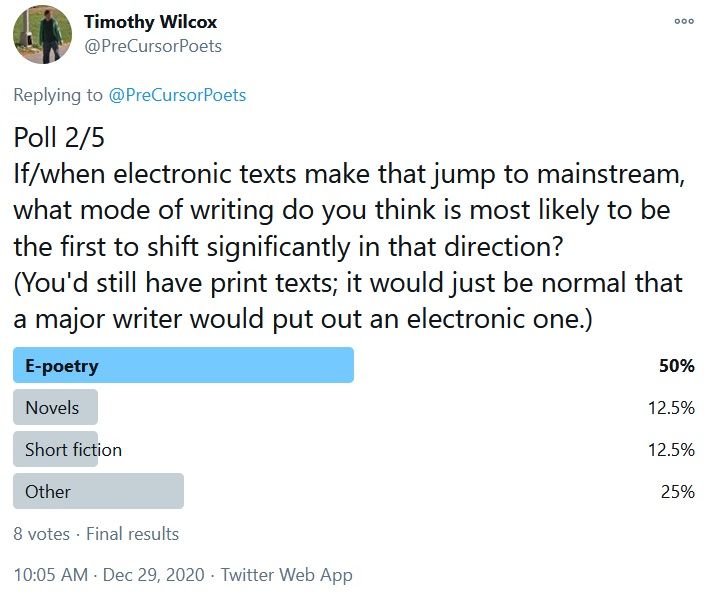

Most people thought electronic poetry would make the jump first. (If you want to start playing around with generative poetry with no technical knowledge, try my guide here.)

One possible reason poetry inspired such confidence is the success of Instagram poetry, which as Kathi Inman Berens wrote, is perhaps "E-Lit's #1 Hit." Berents questions to what extent such writing meets our expectations for electronic literature, and I am further inclined not to count this within this current line of inquiry. The works make little creative use of the technology. Instead, they utilize marketing platforms to sell traditional print books.

Sadly, neither of the two "Other" voters suggested what they had in mind. Drama is one possibility, but electronic writing also offers many radically distinct possibilities. One example, which arguably has already made the jump to mainstream (just not to the mainstream of adult readers of literary fiction) is Homestuck, a graphic novel / epistolary novel / game / Flash* video / etc. (semi-)interactive work. *With support for Flash ending after today, these components have since been updated to other video formats and HTML5.

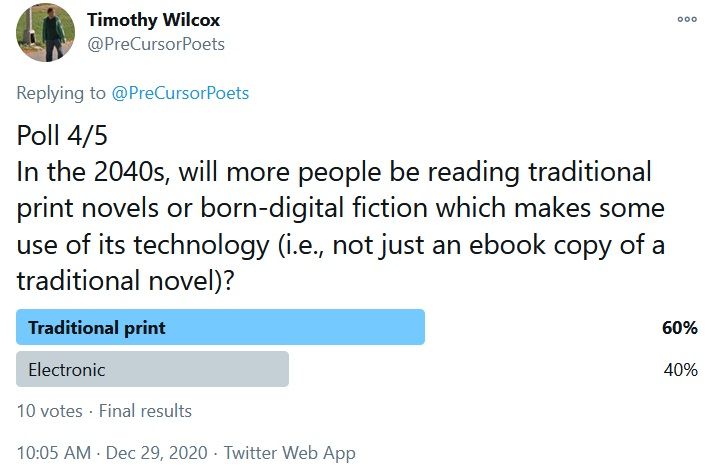

Regarding fiction, most voters thought that by the 2040s, most people who do read would still be reading traditional print-based fiction rather than born-digital fiction. As I note, it may be that the use of e-readers and other such technology might increase, but the core reading and writing experience would remain what we know through print novels.

Four out of ten votes for "Electronic," however, as what would be read more still seems quite significant. If that were the case, it would mean the literary world would have radically changed over the next two decades. Do you think that is possible?

My sense is that plain text, as the most simple and accessible style of reading and writing, will remain dominant, even if electronic text grows substantially in readership and margins become closer. For some people, tools such as Roam (which is also now being used for literary purposes) appear natural fits for their thinking, but our traditional literary forms are flexible enough that I expect they will remain in popular use for a long time still.

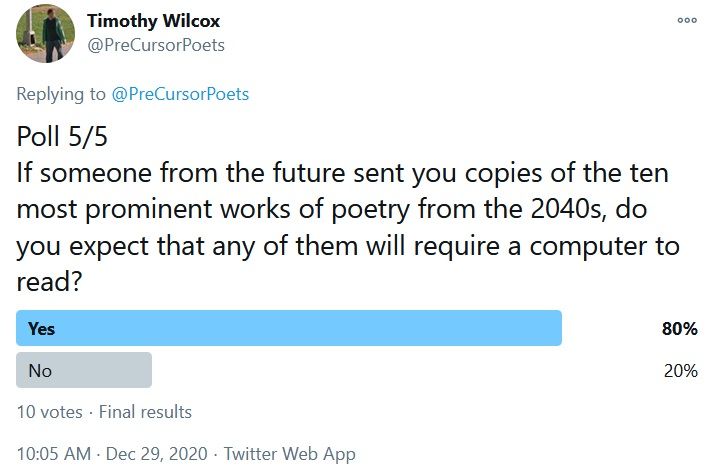

With poetry, however, which tends to lend itself much more readily to overt formal experimentation, the expectations were shockingly high. Eight out of ten voters expect that in the 2040s, some of the most prominent works of poetry will require a computer (or some such device) to read.

This seems very plausible to me. There are already many great electronic poems, and though poetry overall has a fairly niche readership, there is substantial space for increased readership of e-poetry. There is also plenty of room for new poets working in this mode!

These are, overall, very reasonable expectations, which are also optimistic in expecting a vibrant, shifting future for literature – one which does not lose traditional forms, while also bringing us many new ones.

Whatever happens, the current world and history of electronic literature – the precursors of what is to come – will remain crucial. I expect more great things to come, and from these polls, it seems some of my readers share this sentiment.

I would love to hear from people working in or looking to explore electronic writing, or with further thoughts on your expectations for the future of literature.

For those interested in the future of literature, my monthly newsletter brings together at least one work of classic literature, one work of new literature, and one work of electronic literature each month. These conversations are intended to cultivate a creative imagination fit for the digital 21st century world. To get these each month right in your inbox, subscribe below (be sure to confirm):