Promising Young Cyborg Woman

Promising Young Woman just won "Best Original Screenplay" at the Academy Awards, but one of its biggest twists on the genre has largely gone without remark: Cassie's non-violent revenge spree is enabled through technological advancements that simultaneously make the story's originating moment more possible.

The film is most commonly positioned as some version of "feminist subversion" – which is certainly true – but that in itself can often lead to terrible stories. Promising Young Woman stands out through successfully navigating the push-and-pull of utopian promises and destructive potential of the social Internet. Surely, all viewers registered on some level that Cassie was using various affordances of our digital and network technologies, but it is easy to forget the fraught journey of incorporating hyperconnectivity into narrative.

In considering the work as deeply immersed in online life, it is worth noting as well that the writer and director, Emerald Fennell, appears herself in the film as a YouTube star teaching women how to give themselves "blowjob lips" with make-up. This is the machine around which the rest of the drama plays out.

In breaking down how the film's story works – and how it excels through these considerations – extensive spoilers follow. To start, a quick overview of the plot:

The film follows the aftermath (or lack thereof) of a rape which was reported but not investigated. Cassie's friend Nina was drunkenly assaulted in front of a group of men at a party in medical school. Nina dropped out, then Cassie to take care of Nina. After being disbelieved by classmates and the administration, and bullied by the man's lawyer, Nina committed suicide. The film centers around Cassie years later, stuck as a barista, largely by choice, as she is mostly focused on weekly trips to various bars and clubs, where she fakes heavy drunkenness to lure predatory men. Cassie then scares them as she suddenly drops the act – presumably with the goal that they would not risk it again. A comic scene rejects the possibility that she kill them, as she wanders home from a man's apartment in the early morning covered in what could be blood, but turns out to be ketchup dripping off a hot dog.

The seeming opposite of these men who don't take "no" for an answer is Ryan, a former classmate she ends up dating who goes further in sensing that her stated consent to go up to his apartment is insufficiently enthusiastic, and so he offers to take things slow. One of the big twists is that even he had been among the men at the party as Nina was sexually assaulted. The script foreshadows this in the opening scene: Three men are out at a club. Two complain how they can no longer take clients out to strip clubs, while one (Jez) plays the role of the "nice" guy who wants to distance himself from the conversation. The three then spot Cassie, alone, pretending to be exceedingly drunk. Two express interest in taking her home, when Jez steps in as a seemingly safe alternative. He tries to help her come to her senses and then splits a cab with her when she seems to have no way home, but then diverts the cab from Cassie's address to his own where he tries to take advantage of a barely-conscious Cassie. As envisioned by Fennell, he may seem well-intentioned at first, but quickly become predatory when given the opportunity on a silver platter. This possibility is then placed on Ryan as a pediatrician and the man who assaulted Nina (Al) as an anesthesiologist.

Contemporary Storytelling and the Threat of the Future

The set-up for Jez could have happened in an earlier era, but the way Fennell handles it is distinctly contemporary. When he approaches Cassie, she is pretending to look for her lost phone. Then, when she assures Jez that she will get a ride home through an app, Jez gets to say, "You need a phone for that." Where a personal mobile phone would enable Cassie to get a ride to her saved home address in a few clicks, its absence leaves her vulnerable. The phone dynamic gives Jez additional power, but Fennell adds another notable detail on the ride home: Jez cannot just verbally redirect the cab; the driver insists that he add the destination in the app. Now there is a digital record connecting the trip to Cassie's given address with Jez's home address. When Cassie reveals herself to be fully sober, this record implicitly reduces his power.

Cassie repeats a variation of this phone dynamic with the dean of the medical school, Walker, who had dismissed Nina's accusation years prior. Cassie picks up Walker's teenage daughter after school – not pretending to be drunk this time, but acting as a make-up artist for the girl's favorite band. Cassie convinces the girl that the band is set to secretly record a music video at a nearby diner and drops her off there, then tells Walker the girl had been dropped off at the very same dorm where Nina had been. Walker does not remember where that was and, panicking, calls her daughter's cell phone – which Cassie is then holding.

Two things happen in this scene: There is, again, the idea of the cell phone as a vital lifeline to the outer world. Deprived of this, the daughter's risk is multiplied. At the same time, Cassie's predatory capture of the teenage girl was premised on stalking her social media to discover where she would be and what interests would best convince her to enter a potentially dangerous situation with a stranger.

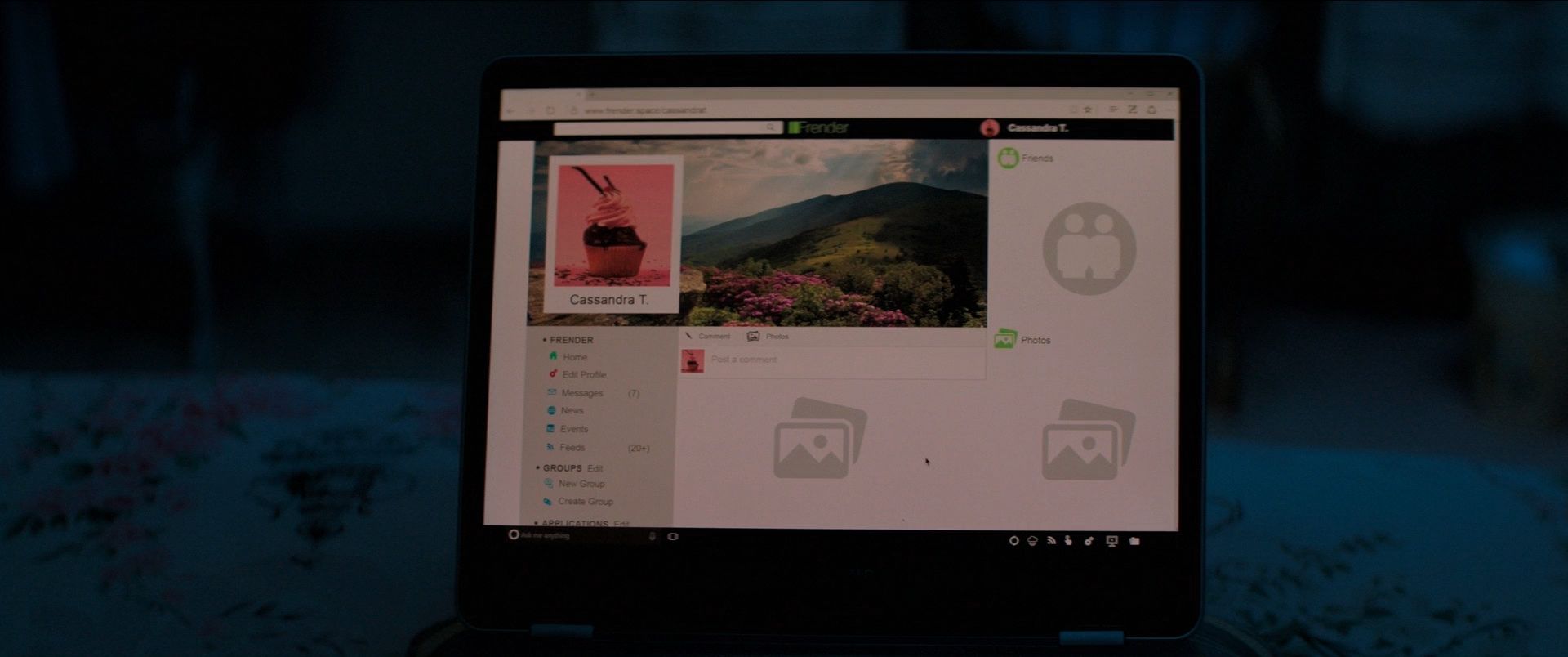

The fictional social media site Frender is also central to how Cassie plans her core revenge. She can gain some personal satisfaction through placing herself precariously in bars, but tracking down the right people and planning the right moves requires the trove of information people share online, including navigating the networks the site offers between these people. For her own self, Cassie opts out of sharing with the site. She seems to have no posts and no friends. Her profile picture is simply a cupcake, and her header image a hilly landscape. This is in part because Cassie has no social network in any sense; her whole life – like Nina's before her – has been consumed with thoughts of Al and revenge. She would also know first-hand how the information shared on these sites could be used aggressively against her.

We are also told at one point how social media changes the dynamics around sexual assault cases. Al's lawyer had attacked Nina's social standing, pushing an image of her as a frequent drunk whose word is not to be trusted. The lawyer is the one person to whom Cassie offers forgiveness. Not only is he useful to the possibility of securing legal resolution, but he appears genuinely understanding and apologetic – in contrast to Ryan, who rushes to justifications and qualifications. As the lawyer is begging for forgiveness and resolution, he tearfully comments how what he had done has only gotten easier with social media: You just need one drunken photo at a party, he says, and that alone can easily flip a jury.

While people may go back and attempt to clean up their online presence, transitional periods can lead to over-sharing. One of the big reveals in progressing the plot – and also how Ryan is shown to be complicit – is that a video recording of the event had existed the whole time. Such evidence would likely not be spread so casually now – instead, treated like Al and his friend do with a big fire toward the end – but, at the time, those involved had no sense of how permanent such a digital record could be, and actually forgot that the video existed. While no one else wishes to speak out in support of Nina, this old phone with a video file can speak to what happened endlessly.

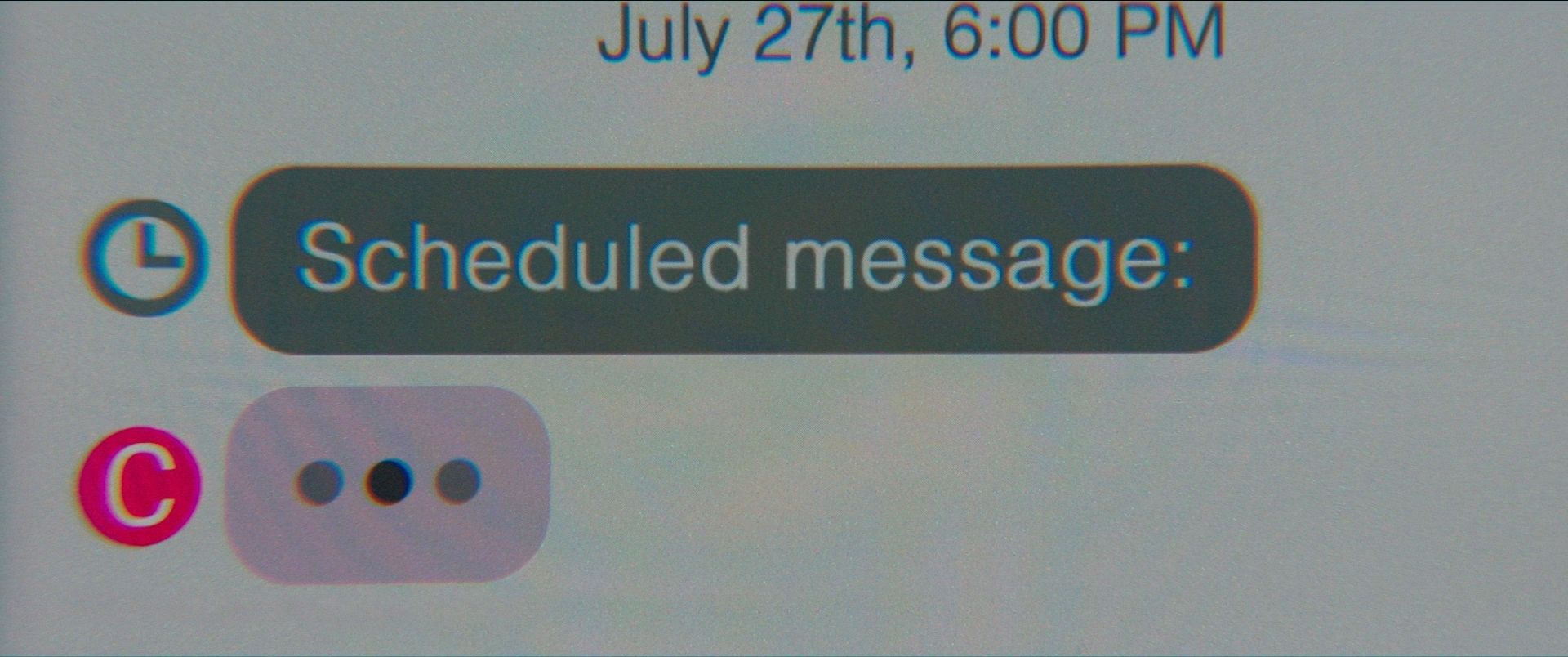

Another dynamic introduced by hyperconnectivity is that stories are not just a matter of people interacting with other people. Now you can have communication between people and machines, as well as machines speaking to machines. In this way, Cassie is able to schedule deliveries as a fail-safe and secure justice from beyond the grave.

The film has one foot in this high-tech (or is it just painfully average-tech now?) world, and one foot in Fennell's earlier models for such a pay-off: The lawyer receives a hard-copy of the evidence in a physical envelope. The latter shows how something of this sort could have existed in earlier eras, but not so widely, invisibly permeating the scene. In giving the whole big screen over to the pending and arriving messages, Fennell gives clear space to the machinic presence of the now-dead Cassie to nevertheless speak directly to Ryan, emphasizing the way in which this will not simply go away just because Al killed her and burned the body.

This ending is given as a plausible counter to a more traditional violent ending for a revenge fantasy (via the LA Times):

“Of course when I first started writing it ... I, like every person in the audience, wanted it to end with her walking away with a burning cabin behind her and sirens in the distance. But then I just got in the room and it just didn’t seem possible,” Fennell said.

“It Just didn’t seem real at all. It seemed completely impossible and it seemed like a lie,” she added.

As I discussed with James McGirk in connecting the simultaneous releases of Robert Stone's story of radio propaganda A Hall of Mirrors and Sergio Lione's Western film The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, something interesting happens with narrative tension with the introduction of the phone. In The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, we see a famous stand-off between three men built around information asymmetry. Any of them could be the quickest to draw, shooting one other, but then opening himself up to being shot by the third man – and yet you also do not want to be the first man shot, so you cannot simply relax. The gun provides a threat with a high level of immediacy: when it goes off, a character can be dead almost instantly. The tension between characters, however, drags the stand-off out for several minutes. The phone introduces new timescales into narrative, but it can be balanced out by similar tensions.

In this era of social media and hyperconnectivity, asymmetry presents new risks. As Fennell imagines it, however, the technology also offers the possibility for some sort of justice, in keeping with the promise of the #MeToo movement. Cassie's victory arrives like a machine from the future – a message scheduled to be mass-delivered, even if the technology had not yet arrived in the early era of phone recordings in which the assault took place. This is the parallel to the opening act's reveal that, actually, the seemingly drunk Cassie is suddenly completely sober and standing up perfectly fine.

Just as the men she catches now have to live in a version of the fear they previously projected outward, the technological underpinnings of the film make it so this threat is always waiting in the future. Fennell does still see women like Cassie as still caught up in the machine in their own ways, but the film overall uses our contemporary setting to imagine a new form of revenge-thriller outside of its guns-blazing predecessors. As Fennell shapes her new model for the genre, I am reminded of Flannery O'Connor writing "A Good Man is Hard to Find":

“She would of been a good woman,” The Misfit said, “if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

For regular insights like this into narrative and expression in the digital era, subscribe below for my monthly newsletter. Typically focused on literature, I connect one new work, one classic work, and one computer-based text each month into some thematic whole: