The Internet Novel; or, Representation and Doom on the Information Superhighway

When William Gibson first used the term "cyberspace" in 1982, he tells the story of a "console cowboy" using a stolen Russian military virus to break his way through the network protections of a mobster to steal money so he can help a girl he fell for get new eyes and a ticket out of town to try to become a star of the hot new simulated stimulation media technology. In "The Lag: Technology and Fiction in the Twentieth Century," Alexander Manshel charts how representations of technologies in literature (radio, TV, internet) follow a consistent lag behind popular home adoption, more pronounced in award-winning fiction than genre fiction. Gibson's thrilling story is an example of how certain genre conventions aid in keeping a story of this emerging technology compelling.

Even Thomas Pynchon in 2013 gives Bleeding Edge a detective fiction core, while having a central character comment how if this were a documentary, it would be mostly footage of nerds staring at screens. Those nerds stand-in for the audience of such writing and all of the endless staring at the internet and staring at phones of alt-lit. Narrating what's actually going on in that moment is a challenge, whether through pure mastery of language or through formal experimentation. The difficulty is enhanced by the added pressure of any sort of realism where one's knowledge of the present or recent past will always have gaps in both overall awareness and ability to parse the timeless from the details that will seem horrifically dated very quickly after publication.

When Joshua Cohen reviewed Bleeding Edge (two years before his own Book of Numbers, but shortly following his Four New Messages), he comments that "cell phones have become the chief antagonists of fiction." Though he's addressing a pivotal moment in 2001 when being always available via cell phone becomes standard, there is not so much of a marketable audience for an internet-centric novel until a decade later, following the boom of smartphones and social media.

Instagram launches in 2010 and is bought by Facebook in 2012. The apps release is paralleled by Jennifer Egan's Pulitzer Prize-winning A Visit from the Goon Squad, vastly effacing her previous literary explorations of social media such as in Look at Me way back in that pivotal 2001 moment. In 2013, Bleeding Edge is joined by other prominent releases tackling this whole networked computer thing: Ruth Ozeki's A Tale for the Time Being, Tao Lin's Taipei, Dave Eggers' The Circle, etc. While some writers such as J. M. Coetzee swear off letting the technology into their fiction, others seek to conquer this literary challenge.

As Cohen recognizes, though, doom is coming for the novel. Dynamics like chance encounters in the street and long-term gaps in communication remain possible, but increasingly unnecessary and so narratively contrived in service of their traditional role of creating alternating narrative tension and plot progression. In 2013, the old social world that underlies centuries of literary frameworks is dying. Surveillance Camera Man uploads his first YouTube video. Elsewhere, video game outsiders use Twine to make small-scale, emotional, narrative games.

When Cohen launches his Book of Numbers in 2015, the novel's marketing takes the form of a Bloomian willful misreading of his precursors. Rolling Stone hails it as "The Great American Internet Novel," "an attempt to reclaim a sense of humanity in the digital age." The phrase is repeated in other coverage, such as in introducing an interview by Gideon Lewis-Kraus for The New Republic, in which Cohen adds another wrinkle to writing in the era: digital omniscience, both as a threat against dynamics of unknowability and as the way in which the internet consumes writing and then uses it in algorithms and training. His comment that "it’s time that writing took something back from the Internet" presents a sense that there's something here that has not been done, that though a parallel is ultimately drawn between the idea of the "internet novel" and the "immigrant novel," he is doing something new here which is vital to the medium.

Whether in print literature or digital literature such as Twine, the desire to represent a sense of "humanity" or something like an immigrant experience into a digital wilderness emerges as a Romantic reaction to the growing proliferation of technologies in which we are rendered (in collaboration often with ourselves) as profiles for public viewing and psychological types for algorithmic manipulation. (In the world of visual arts, Eyebeam hosts The New Romantics in 2014.)

Who is that person staring at that screen? What is it really like to be engaging with all that information, all that media? What is this new social world we half receive and half create?

The "internet novel" expands as a wider concept to capture all the different attempts to capture that experience in writing. From its early cyberpunk origins to more recent narratives, this experience has also been frequently mediated by drugs in much fiction. Maybe people experience their use of networked devices like that in real life, too. I don't know. Frankly, I don't want to know. Even more tragically, whether Twine-coded or altlit-coded, these people are also often down and out in Brooklyn or some such made-up meatspace region.

My instinct when it comes to fiction-where-the-characters-are-using-the-internet-and-it’s-important-to-the-story is that it absolutely cannot take place in major cities. idk why but we need to be writing Internet Pastorals, trust me on this.

— 👩💻 audrey 👩💻 (@audsnowmat) June 3, 2025

The internet novel isn’t about irony poisoning or doomscrolling, it’s about the strange and sincere intimacy the internet engenders between people who know they’ll never meet. This is also why the best internet fiction follows sad perverts on webcams. In this essay, I will

— kelly erin (@kelly_erin_) June 9, 2025

It's a bleak world which engenders a sometimes reluctant but nonetheless real love for the connections found online, a dynamic well expressed in Tao Lin's "Some Of My Happiest Moments In Life Occur On AOL Instant Messenger." In contrast to the sense of digital omniscience, these moments are ephemeral. They came and went and AIM itself is long-gone, too. You can experience some of the feeling of it through the Emily is Away series, though this is still very incomplete (and lacks real human connections).

almost everyone who tries to define “the internet novel” seems to be really talking about “a novel about how I personally experienced a few websites between the ages of 10 and 24 in the early 21st century” and idk how to tell you guys this but that is not what “the internet” is

— genre petty (@pourfairelevide) June 8, 2025

A key challenge in pinning down the experience of life on the information superhighway is that how we navigate, process, and recall such experiences is shaped by widely different formative moments, within and across generations. We end up with less of an internet novel and instead a Tumblr novel or a 4chan novel or a Twitter novel, or an early Facebook novel or a boomer Facebook novel, or any other granular accounting for the popular haunts of the author and the author's social circle.

All of these can be quite interesting in their own ways, and can often be a great record of something which, like AIM, is likely now or will soon be gone—whether fully shut down or utterly changed. Much born-digital literature is already, technologically, unreadable.

But all this recent "internet novel" discourse was prompted by a recent essay, "Crushing Banalities" by Sophie Kemp. The main focus is Allegro Pastel by Leif Randt, and the frighteningly relatable banality of the characters' lives (and, yes, ketamine is involved). But over the course of the review, Kemp (who also has an internet novel, Paradise Logic) addresses this whole context and what the ideal internet novel would set out to do:

This hypothetical True Internet Novel would not use the words Instagram or meme, or even based. It wouldn't be self-conscious. You would just be able to tell by the nature of the sentences that the writer of said novel had only ever known life on the internet, and nothing else. It would try to make us feel something being online could never make us feel.

This, I feel, gets to the core of things better than much of the discourse which followed, which very quickly was not even really responding to Kemp's review.

This points towards a problem no one is raising regarding the possibility of the ‘internet novel’, namely what form it will take. It’s not enough to provide a phenomenology of online experience. Too impressionist. The only form is a self-reflectively universal/encyclopaedic form. https://t.co/RSfM2kww90

— nom (@14JUN1995) June 9, 2025

One part of the challenge about an internet-era novel is that the characters are interacting with small pockets of a vast global network, which nevertheless do change social dynamics in ways challenging for narrative conventions. Another challenge is that an encyclopedic work loses almost everything humanly interesting about the internet.

What, though, would it look like to have a more "universal" internet novel, not just one person's adolescent and early adult experience of this digital, hyperconnected world?

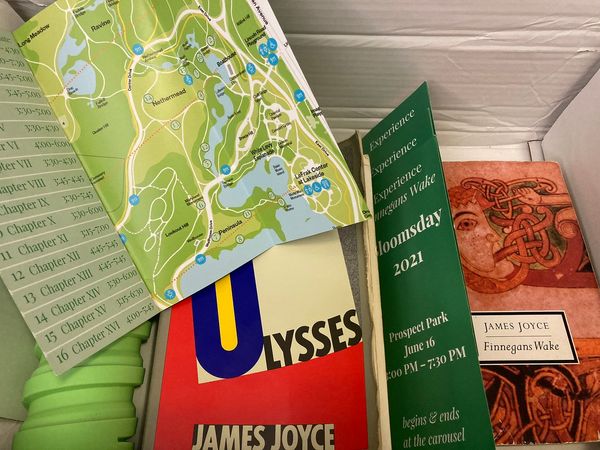

Like the invented claim that early precursors of the internet were built as a means of communication that could survive a nuclear war, James Joyce is recorded as saying that if Dublin "one day suddenly disappeared from the Earth it could be reconstructed out of my book." The latter, as a true capability of Ulysses, presents a real solution for the earlier problem; however, while many excel at writing about the bleak, paralyzing aspects of always-online life, it has proved harder to achieve this power for truly recalling to the imagination the internet, which is, as we know, already dead.

For now, then, we read on through all the slop that comes our way—via feed or print—as we do sometimes glance wonders that hint at what could be.