Case Study: Percival Everett Tunes in to Voices From Afar in Telephone

The May 2020 novel explores the technology and game of telephony in our digital age.

Ordering a jacket on eBay is not a dramatic moment. To the extent that writing about digital technology inevitably bears the trace of the science fiction that got there first, Percival Everett’s Telephone drains it of that style.

Protagonist Zach Wells is a professor, and his students occasionally look at cell phones, but it’s just something they do. It’s not a big deal, some kind of dawning of a new era. Wells’ concerns are old concerns – in life, in literature – focused on campus drama (interpersonal, professional) and home (marital, medical). So is Everett avoiding the digital? No, it’s central.

Speaking Into the Abyss

Wells is avoiding the non-digital, and the weird, seemingly meaningless glimmers of connection which come from online offer an escape. His attentiveness in this is, seemingly, rewarded, as he makes genuine and desperately needed contact with a group of women trafficked over the U.S.-Mexico border to work as slaves in a clothing factory.

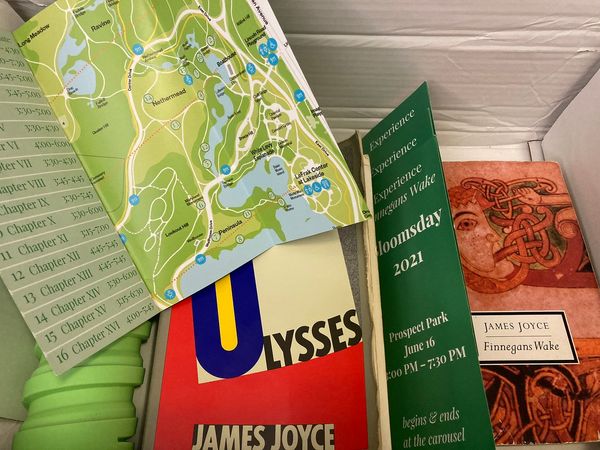

This is at least what happened in my version, one of three released simultaneously. I’m going to write below about the second half of that version, so I will certainly be spoiling details about some text, but maybe not the one you acquire. What is expected of us is that we talk about these different books: the different texts, what we got from reading them, and then as our discussion goes on, we experience something like a game of telephone. What I would come to understand of Telephone would, ultimately, be a product of how we can think to talk about it, not just what is directly there. Our memory fails us, but the basic stories remain.

That failing of memory is what becomes of Wells’ young daughter who develops Batten disease. As the functioning of her nervous system declines, she eventually ceases to recognize her parents, but she does for a while see in her dad his made-up protector character, Daniel.

One of the big thematic topics related to the narrative uncertainty is Wells’ repeated questioning of how a just God could allow such a horrible thing to happen – a child getting a fatal disease, suicide, kidnapping, murder – and he thinks about Leibniz’s best of all possible worlds theory, in which he attempts to explain away the problem of evil by suggesting that, as bad as things are, perhaps this is still the best of all possible worlds. But if we do live in the best of all possible worlds, which of the three possibilities presented by Everett might that be? How can we possibly assess that, balance out the pros and cons, and be confident in belief?

Of all possible worlds this is the one in which I had landed.

Wells cannot take that leap of faith – or at least he certainly didn’t in my version – but he could act. He could enact good. In finding a note hidden in the jacket be buys off eBay, saying “Ayuademe” (“Help me”), Wells finds the perfect escape and chance at imagined moral redemption. This is, perhaps, someone he actually can save, so he becomes obsessive over this possibility.

The Possible Worlds of Connection

For just a moment, him tracking down the source of the packages, traveling across states, and stalking out a mailbox and a post office seems paranoid, but Everett does not let the story dip into The Crying of Lot 49. Wells’ suspicions are very quickly vindicated. The paranoia in the novel is, instead, experienced by the daughter. It is a product of neurology, not culture, and Wells’ concerns – about race, about the dangers for women in the world – turn out to be perfectly correct.

The moral justness of the search is made clear when the communication stops being the indirect secreting of messages via eBay packages, and when Wells is able to make direct, face-to-face communication with one of the women in the back of a small store. The clear and successful communication via eBay is an idealistic moment, a story he feels is too crazy to tell anyone else. Only a class of poetry students is able to understand and help.

When his daughter first has a flash of not recognizing him, and then enters back into what he understands is now only a temporary recognition, he turns away, looks at his mobile phone: no signal. Whether they should even tell the daughter that anything is seriously wrong is an ongoing debate between Wells and his wife. Wells’ sense is that he should, but he doesn’t. He finds himself no longer able to achieve that sort of communication in life. No signal.

Zach Wells is not very online. He is old enough to have grown up without the Internet, and he finds little use for it in his life as a geologist. That digital world plays a largely background role in the novel, and yet already it is only through crazy-seeming, cryptic messages coming from online orders that he is able to truly hear another person’s message, to truly go out and offer comfort and help. After he fails to recognize his colleague’s despair, he thinks,

Sad in so many ways, that I had been too tone deaf to hear her message or her plea, and that, even if I had understood her, no one was more incapable than I was to offer comfort or help.

That incapability runs counter to his attentiveness to the online-based message, but his ability to truly help does not happen alone.

The poetry students show up suddenly. Crucially, they believe, and so they act. Everett sees to it that readers of Telephone need each other, too. It is incidental (not part of the long process of planning, writing, revising, publishing) that book talk has moved wholly online, but it is far from inappropriate. For all the shortcomings of that networked communication, making oneself attuned to that signal – however forced – presents this moment of possible redemption. However other versions of Telephone may end, Everett shows that possibility is there.

To learn more about new fiction, literary trends, writing in the age of online commerce, poetry, and more, subscribe to my free monthly newsletter. I bring together the latest and greatest of my own writing, new literature, literary history, and a curated selection of other sources around the web. Sign up now and I will also be sending out an invite to a free mini-course delivered via email soon: