Week 2: Digital Mirrors

Last week, I introduced some of the general terrain of literature in the 2010s and the challenges which limit the turn toward writing which captures the texture of digital life. If you have not read that, you can find it here.

If the goal is to capture in literature the experience of being immersed in hyperconnected systems, then works which simulate the interface of existing communication platforms may seem like an obvious solution. The experience of the game, then, is the experience of the hypercommunication itself, yet stories will typically be told at the pace narrative demands and not the pace of real-life exchanges. What are these narrative demands, and how do they manifest?

Stories With Characters: The Problem of Emily Is Away

Stories typically have characters, or at least one. If your story is structured around a communication platform, you are probably going to add in at least a second character. Often, the story will then be largely about the relationship between these people, how that (developing / shifting / tenuous) relationship can be read through their exchange, and how what is exchanged alters that relationship. Remember, hyperconnectivity is not just about person-to-person exchange, but also person-to-machine, and machine-to-machine. This social-driven story structure encourages focusing reader attention on how people communicate with other people.

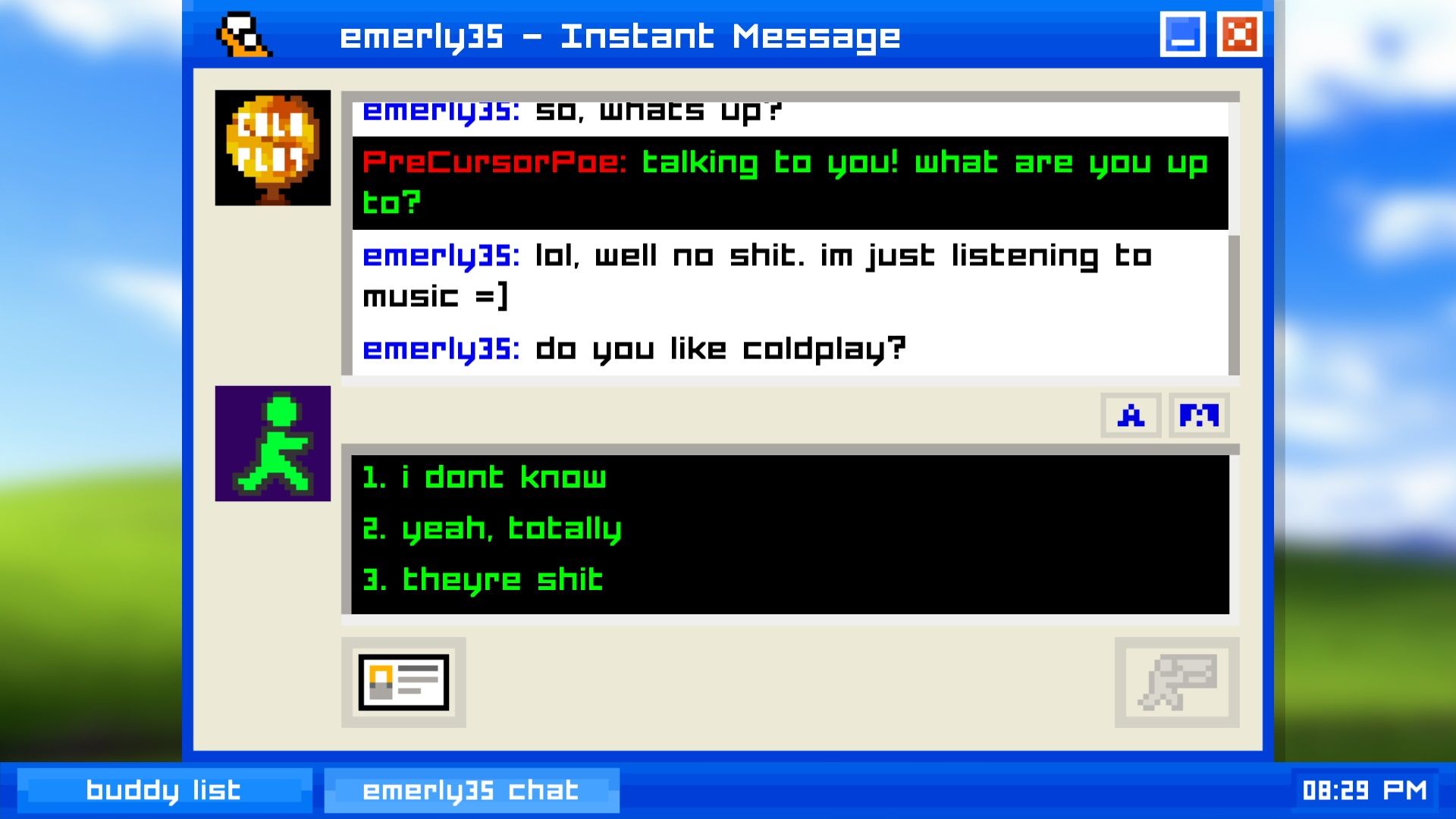

Two-person social-driven narrative focus is the foundational structure of the original Emily Is Away. The work (released in 2015) is set in the mid-2000s, in a simulation of AOL Instant Messenger from 2002 to 2006. You have a pseudonymous screenname (which Kyle Seeley lets you set to whatever you want), and when you log-in, you get access to your Buddy List. A few other characters appear here, and we can get shifting glimpses into their lives by reading their statuses and profiles, but the vast majority of the story is told entirely through the private communication between the player-character and his friend Emily.

Though not the first of this kind in digital form, the overarching literary model for this narrative approach is the epistolary novel. Short of selling a stack of unbound pages, epistolary novels were themselves something of a simulation of the real-world exchange of letters, with some compression for practical reasons. Already established in classic examples of epistolary novels is the exploration of a social web wherein multiple characters reach out through the private, composed medium of letters in intersecting, sometimes competing ways. Such dense webs become newly relevant in creating a mirror of online communication, as many people are in constant communication, and the tendency toward short, quick messages means that each participant can easily be actively engaged in multiple conversations at once. In Emily Is Away, we see a glimmer of this reality through the buddy list, each entry a potential simultaneous conversation.

Seeley, however, focuses on just the one exchange. The narrative demands we focus on the central story, which is how the player-character and Emily drift apart and communicate over instant messaging. The work mirrors the medium well and so provides a way of looking back. In addition to the choice of pseudonym, the custom statuses, and other aesthetic details such as text color and buddy icons, the work uses its chosen form to explore two powerful communication tools: an indication when the other user is typing and the away status.

When Emily is composing a message to the player, a line of text appears in between the chat history and the message box: "emerly35 is typing..." This bit of machine communication gives the work an added temporal dimension and slight look into the other character's process of composition. No response ever takes too long to come, but we can see when she starts typing up a response, and so we can see how directly engaged she is with our conversation rather than off talking to someone else or doing anything else on her computer. We can also at times see her start typing, stop, and then start again. This reveals a pause, a moment of either more careful consideration of words or a correction. From this, we also know that we are transmitting this information when we see the player-character hesitate or revise while filling in a full message from our chosen reply. Delayed responses or a turn away from fluid conversation unwittingly reveal growing strains in a relationship. Handwritten letters might let slip similar clues, which can then be erased when written into print for a novel, but Emily Is Away captures this on the screen for us to read.

The titular away status as well is informative. After the player-character and Emily graduate high school and physically move apart, their relationship to each other becomes rooted in their online presence. The more one is "Away," the more that person is away in a wider social sense. All you can interact with then is the away message: a static bit of information communicated from your friend to the machine, and then from the machine to you on demand. As conversations die out and either Emily or the player-character go "Away," the relationship becomes decreasingly a real one with each other and more a technical one merely implied through the "buddy" list.

Stories About Characters vs. Stories About Mediums: The Problem of Digital: A Love Story

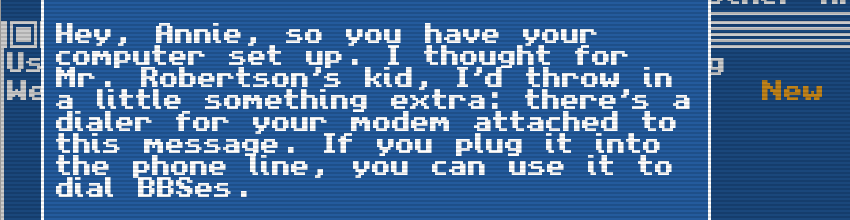

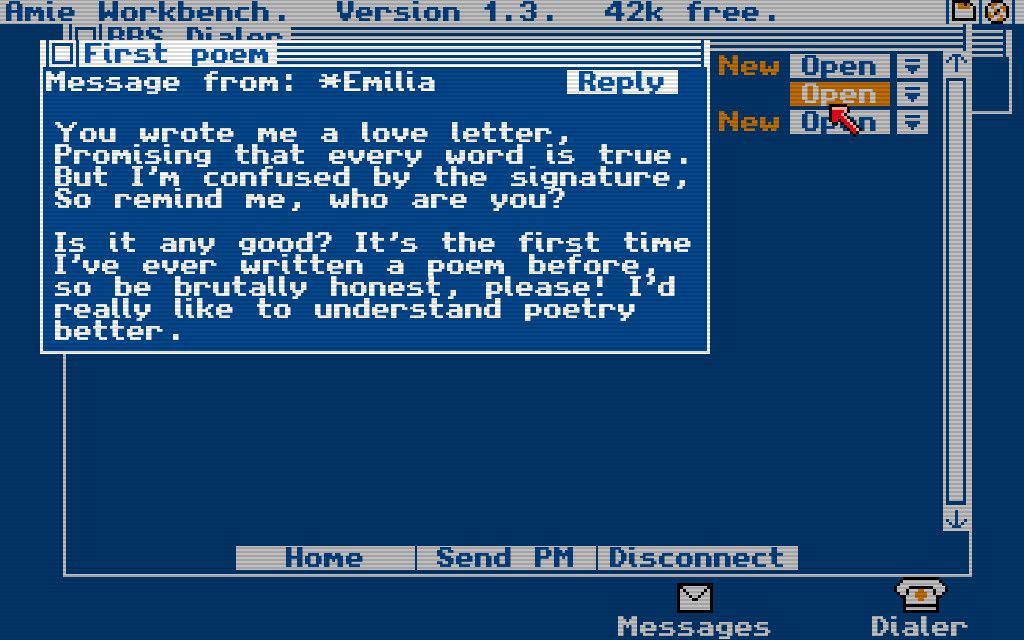

Christine Love's Digital: A Love Story preceded Emily Is Away by five years, and goes back in content even further, to the 1980s. The visual novel simulates online bulletin boards, including public posts, private messages, and a series of attachments through which you progress via unlocking new connection tools.

Though I ended up describing some of the ways Emily Is Away uses and comments on its medium, the narrative focus is on the trajectory of the two characters' relationship. Digital is, as described, primarily a love story about the digital: its technical history, its early popular culture, and its new social offerings. In moving back from instant messaging to a fuller bulletin board system, we get a broader selection of content, but in creatively engaging the medium itself, you end up with a narrative which demands attention to the distinct features of the medium over an extensive simulation of living with that medium. This is exacerbated here by two big factors:

- Because simulating existing platforms like this is still novel (somewhat true even still today, and especially for Digital's 2010 release), the work cannot help but call attention to this framing. In authoring an original narrative exploration of the medium, Love must carefully consider how to structure a story around these given components, and the reader in turn is prompted to consider not just the story itself but the novelty of how Love makes it work in this form.

- Because Love is simulating an existing medium and going back over twenty years, the work further becomes not even entirely about story, but also a fun way to go back and interact with something like that older medium. For older players, this might take the form of nostalgia (and you can see similar in the reception to Emily is Away), and for younger players, an opportunity to experience things not present on their more modern systems. To the latter point, one of the distinct formal elements of Digital is that you have to actually pull up numbers and dial into the different communities, imposing a minor burden which younger audiences could otherwise avoid entirely.

In composing a love story about the digital medium itself, Love simulates the computer terminal and communication software, but constructs an alternate history. The story shifts away from a realistic portrait of life on a 1980s BBS and instead into a cyberpunk adventure of trying to save an artificially intelligent poet. This narrative interest is placed over the mirroring of the real system, and so the created experience is moved away from a direct encounter with hyperconnected reality and toward the needs of this specific story.

Stories Over Time: The Problem of First Draft of the Revolution

In terms of release schedule, Emily Short and Liza Daly's First Draft of the Revolution comes out between the other two works discussed above (2012), but in terms of medium simulated, we are moving even further backward – much further. The titular revolution is the French Revolution, though the story is not especially focused on the revolution itself as we typically understand it. Like Digital, First Draft explores an alternate history. Some characters have magical powers, but even that is not largely the focus. That spectacular, fantastical variation on history is just part of a wider feminist project of exploring the revolutionary moment through a consideration of the periphery – such as in this case, the careful letter writing of a young woman.

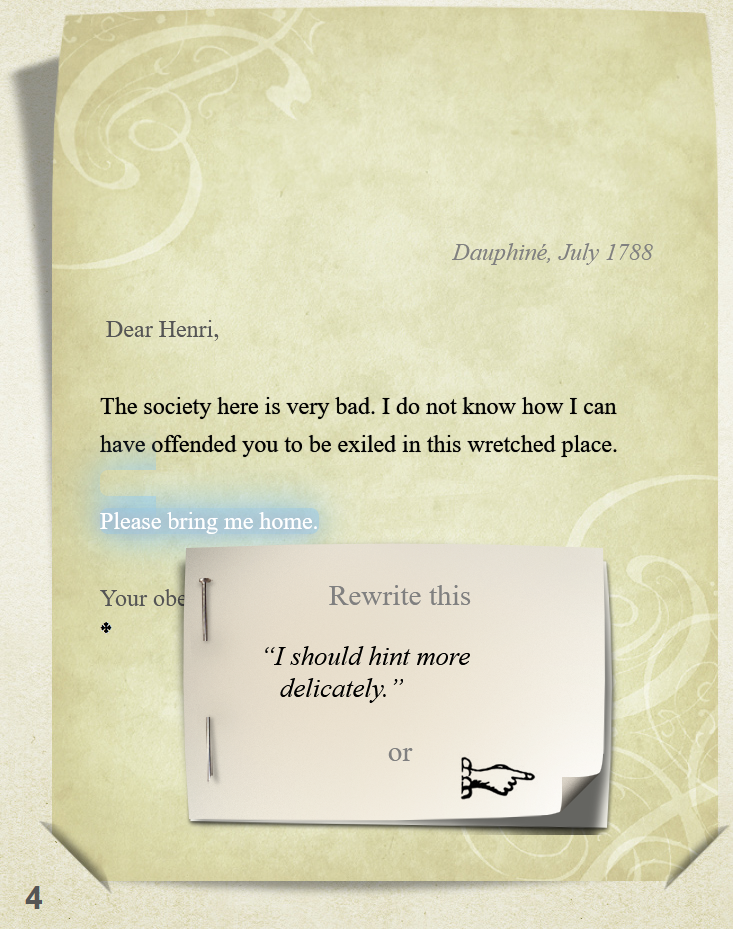

The major formal innovation of the work is that instead of an epistolary narrative told through completed, sent letters, we see the letters in drafts and are able to interact with its revisions. Selected parts of the text are clickable, revealing pop-up boxes which contain internal thoughts reflecting on what is being written, its audience, and the intended effect. Rhetorical choices are weighed against the practical social realities of the period. Short writes from the perspective of a few different letter writers, and so we can compare the writing and considerations of Juliette – the young woman banished to the countryside by her husband – and of Henry, her husband who has that demonstrated authority. Juliette, however, is the central character and our primary point of consideration.

One thing that is not considered, however, is the material practice of writing and revising in the eighteenth century. It is alluded to in the beginning that, within the story, the characters are going through multiple full written drafts and then copying over a finalized version later to send. The interface, however, presents all of this on one fixed page for us, designed to look like a single sheet of paper. The changes happen internal to this page, just as they would in a word processor. This is complicated further by the fact that Short uses the magical conceit to have the letters function like email. The final parchment the letters are copied over to are magical pages which are enchanted to instantaneously transmit the contents to a similarly enchanted parchment owned by the recipient. This does away with the distance of time and space which, you may recall from last week, Litt and Cohen suggest as central to shaping the tensions which underlie traditional narrative frameworks.

Short's story, then, is not written in the temporality of eighteenth century communicative life. It is written in the temporality of later more instant communication. The story progresses over days and weeks, instead of those being the travel time of each letter with days' worth of story happening in between. In limiting how much happens in the surrounding life, Short is able to better keep focus on the thoughts of her protagonist. What Short is doing here works well for the narrative purpose of exploring internal considerations of social propriety, but the network of recipients is kept limited and even this compression from the pace of an eighteenth century story is still far from the constant communication from and to both humans and machines in the hyperconnected age.

First Draft is, unlike the two digital mirrors above, not fully trying to explore a contemporary medium. It is using digital technology to give us a new way of interacting (here in a directly given way) with older forms of communication. This does work both ways, however. In exploring the social context of writing and visualizing the process of writing, First Draft can help us adjust our approach to digital communication outside of its narrative frame.

Conclusion

Each of these electronic texts gives us something to explore in terms of how our digital, networked technologies structure writing and communication, yet none gives us a full experience of hyperconnected life. The purpose of crafting this sort of digital mirror instead of just going directly into an existing network is that you are crafting it toward a narrative with particular narrative needs.

As we move next week into print novels, we will have much different considerations, but the incorporation of elements of digital communication into those texts will function similar to the descriptions above. Through creative application, what we get is partly a mirror of the digital world, but also a way of glimpsing through that surface: seeing how this form manages relationships, enables expression, and perhaps puts us under greater scrutiny in ways we may not desire.

This is Week 2 of a 10-week course of study, offered alongside my free monthly newsletter. These special topics will be going out each Friday through to mid-September. Additionally, I will be inviting those on the email list to attend a series of connected Zoom sessions, including live discussions with some of the authors being studied. Subscribe for free below: