Navigational Text

Below is a brief introduction to J. R. Carpenter's ...and by islands I mean paragraphs (2014).

Read ...and by islands I mean paragraphs for yourself online here.

Then, consider registering to join a free, live, open group discussion with J. R. Carpenter – scheduled for this Saturday, January 16th at 12 PM EST.

Reading is fundamentally navigational. One basic level of literacy is the ability to navigate linearly through a linear text. A higher level would be the ability to take in information at a glance and move more liberally through a long selection of text, such as finding the one paragraph in a book which describes the concept you want to explore.

With word processing on computers, a further level of navigation is technological literacy: the ability to utilize elements of the interface, through devices such as a keyboard and mouse, to move to different sections, pages, precise character points, etc.

Above this is the metaphorical referent of navigating through physical space. Locative narratives are navigational in this way. As a reader, you must physically move through the world, being tracked along the way by GPS technology, and your access to new parts of text are guided not by knowing how to navigate a page (or its simulated equivalent on a screen) but a specific real-world area. The most famous instance of locative media would be Pokémon Go, which was non-narrative, but did embed information locationally, guiding users to cluster around various local hot-spots. You can perhaps imagine how such technology could be used to situate narrative beats in a particular space and immerse the reader in the navigational behavior of a character.

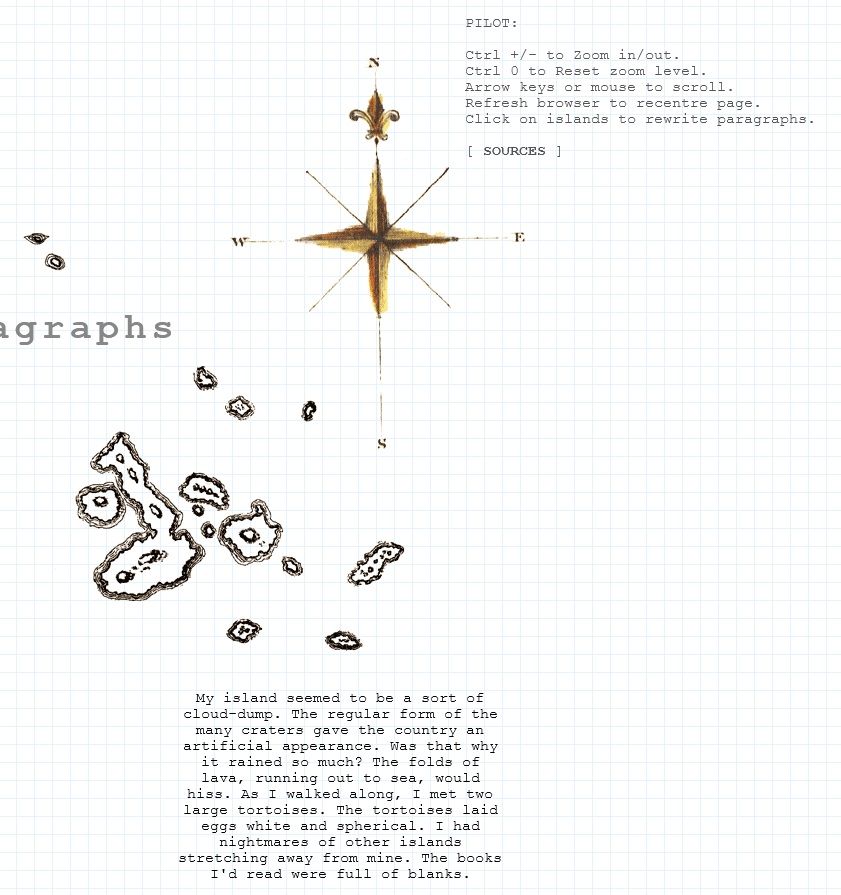

J. R. Carpenter's ...and by islands I mean paragraphs combines elements of (simulated) physical navigation and navigating a computer interface. Previously, Carpenter had used Google Maps to place narrative components into a more familiar map view. Here, the background is a light grid, over which is placed sketched images of islands.

This is not a locative narrative, nor would it be ever viable to achieve any substantial readership for a work which required reading an actual drawn map of the sea and physically traveling to various islands. Still, it is worth keeping in mind the existence and logic of locative narratives. Narrative is not necessarily a linear thing given in a sequential order. Text can simply be in places, and we as readers have to travel to that text.

The page defaults to a central position, with the ability to scroll left, right, up, or down – reimagined through the image of a compass rose as cardinal directions. Instructions visible in the top-right corner explain that you can navigate with arrow keys. The instruction "Click on islands to rewrite paragraphs" explains not only the possibility it says, but also implicitly informs us that islands are the primary unit of text here (and by islands, I mean paragraphs).

While we might imagine the sketched islands as referring to a fixed place with some objective existence – marked by coordinates, by certain features, there for us to encounter – the paragraphs are personal. There's a speaker here telling a story, but the text keeps changing. Like in many of Carpenter's other works, these are variable texts. Component parts of each paragraphs shift independently, though each island generally coheres around a given topic. As she write in her sources page,

Individually, each of these textual islands is a topic - from the Greek topos, meaning place. Collectively they constitute a topographical map of a sustained practice of reading and re-reading and writing and re-writing islands. In this constantly shifting sea of variable texts one never finds the same islands twice... and by islands, I do mean paragraphs.

The first island we see when we open the page are the Galápagos Islands in real life and "isle6" in the source code. There we can see the core structure of the line: "My island #{island} #{volcano}. #{climate} #{beaches}. As I walked along, #{walk}. The tortoises #{tortoises}. #{dreams}. #{complaint}".

The terms in the braces are variables, corresponding to the banks of text above. Accordingly, "#{island}" can complete the opening "My island" with lines such as "seemed to be a sort of cloud-dump." or "- a little world within itself." These are just two of ten such variable possibilities for just that one half-line. The full paragraph has eight variables, and each variable is selected independently, so there are many possible overall variations of this paragraph.

If you do not click, the text will eventually shift to a new variable on its own. If you click, the text will shift as often as you click. The variable nature of the islands (by which I mean paragraphs) is thus not wholly dependent on the reader, but does reward a sort of active listening.

Part of what enables the variable nature of the text is that the "I" is not one fixed person. Sources are given at the bottom of each island's code. For "isle6," we see that text was taken from Elizabeth Bishop's "Crusoe in England" and Charles Darwin's The Voyage of the Beagle. Other islands might draw on various other texts such as Robinson Crusoe itself or William Shakespeare's The Tempest. This is thus a highly literary sea. The sea as imagined through literature is here (at least in part) made navigable, in a manner which simulates moving – through vast expanses of nothing – from island to island.

Notably, though, whereas each time one returns to The Tempest, the text itself will be the same (even if our understanding will shift with age and experience). Here, that is not the case. You leave one island for another, then another. Eventually, you wind up back to an earlier point, but the text is different.

Outside of digging through the code and conceptually understanding the different possibilities, readers will never encounter the majority of possible expressions. Within readerly limitations as well, a reader has further choices: Sit on one shore forever trying to exhaust all possibilities, or explore broadly?

To return to my starting point, you can imagine a similar sort of consideration with a typical collection of poems. You read a short poem, and then you can go read any other. Situating such exploratory energy on an actual map, however, and having readers navigate through blankness to find and listen to different islands greatly expands our possibilities for navigating text.

Islands are paragraphs, but a paragraph you encounter at one moment is not the whole of what that island has to say, nor does any one island say everything there is to hear. Thrown into the middle of the sea – and by the sea, I mean literary history – how do you begin your travels? Where do you end your voyage? Wherever you leave off, you might find that parts of islands stick with you – and by "parts of islands," I mean variable texts.

Further Reading:

"Digital Nature" – On J. R. Carpenter's This is a Picture of Wind: A Weather Poem for Phones, a 2018 work which is currently updating with new content on Twitter.

"The Self-Similar Coast" – On J. R. Carpenter's The Pleasure of the Coast: A Hydrographic Novel.

"Hearing Islands, Islands That Hear" – On J. R. Carpenter's Etheric Ocean.

As noted at the top, J. R. Carpenter will be speaking on Zoom this Saturday. All are welcome.