Strange seas of Thought, alone

PreCursor Monthly — August 2020

If you have not been following along with my "Literature and Hyperconnectivity" posts, I recommend reading through them. On July 17, I sent out Week 2: Digital Mirrors, in which I discussed three digital epistolary narratives. This sort of writing – making significant use of computer and/or network technology – is known as electronic literature. July 17 coincided with the annual Electronic Literature Organization Conference and Media Arts Festival, which was immediately preceded by and partially overlapping with the 31st ACM Hypertext conference, both of which transitioned to virtual for this year.

Over time, I intend to do more work introducing electronic literature through here, but to get an overview of the current state of the field, you might look through the Electronic Literature Organization conference website, which has an extensive archive of recorded live events, asynchronous talks, panels, proceedings papers, and so on. Especially appealing perhaps is the "and Media Arts Festival" part. The virtual exhibitions collect dozens of new works, each with substantial introductions. For now, I will draw attention to two in particular:

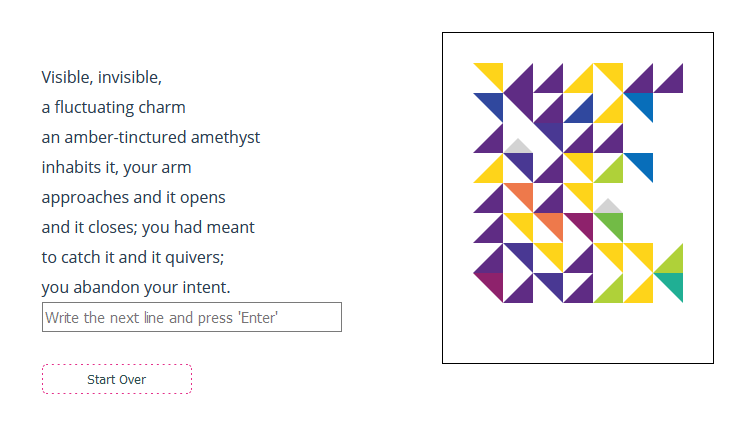

- Patchwork Poetics: An exhibition created by Anne Sullivan, Katie Farris, Marie Elena Margarella, and Zehua Chen, which visualizes some elements of poetry. Featured in ELO's (un)continuity exhibition.

- I look, but I can't see: A Bitsy game created by Rachel Donley, which places the player in a room to explore, think, dream, remember. Featured in ACM's Climates of Change exhibition.

Learning to read quilts

Patchwork Poetics translates poetic lines into "a digitally generated quilt," as part of a feminist exploration of poetry in relation to craftwork. As suggested in the introduction to the work, earlier works such as Shelley Jackson's Patchwork Girl and Deena Larsen's Samplers involved a similar consideration of "the interconnection between text and textiles," but where those earlier works produced writing inspired by quilting, Patchwork Poetics produces quilting inspired by writing. The introduction goes on to note that quilting and poetry have both in the past supported subversive storytelling, and so this tool is intended to extend that possibility. The installation is to designed to recognize elements of poetry and produce this aesthetic form:

The individual patches of the quilt are determined by poetic sound devices present within each submitted line. Devices such as assonance, consonance, meter, and rhyme can be represented, although the goal is not to create easily legible data visualization, but rather use the data to help generate an aesthetically-minded quilt design.

Here is a sample I put in. You can easily produce similar images with any text you want (including your own original text) on the website, which goes through four examples of its own with some explanation of what considerations go into the images. As is true for many digital media projects, the ability to play with text is central. The point is not just the given examples, but what this prompts you to do with or think about text, as you are made able to encounter poetry in a new way.

Learning to see unreality

In I look, but I can't see, we play around with space and the mind. Represented as a pixelated eye on the screen, we move around and interact with objects. Moving our eye up to the sun, we wake up from a dream. What is above us now is "just the ceiling," and the shapes we saw before part of the ceiling's design. Shifting our gaze to the left, we see a spider, triggering a memory from childhood, though the narrator is uncertain this memory is quite accurate.

The game goes on like this. Shifting our gaze back down, we move from the ceiling to the wall, and so with our eye as player avatar, we discover a way of looking around the room. At the same time, the writing guides us through ideas about our imagination. As a visual medium, video-games are typically structured around seeing things. Environmental storytelling is a popular approach, but here a blank wall is equally suitable (perhaps more so) for inspiring reflection. Our spatial movement becomes the space of the room as well as our mind as memories or dreams overtake our vision.

The work asks us to consider senses we do not have access to, and what we might not be seeing. In the exhibition description, this is given a wider context: "We face challenges we’ve not prepared for, both the sudden advent of the pandemic and the myriad complications of climate change that grow steadily under the passive gaze of people in power." The pandemic is, of course, the "Invisible Enemy," and something like climate change escapes our means of seeing. Timothy Morton calls things such as climate change "hyperobjects," and Rob Nixon describes climate change as "slow violence," something typically outside of our sense of perceptible time, but which can be made visible through literary narrative by writer-activists.

We look, but we can't see. Creative works offer us one source of vision, while projects such as Patchwork Poetics offer another approach, making visible elements of literary history we might otherwise miss.

Learning to imagine futures

In my June newsletter, I included this brief introduction to the interactive fiction work A Mind Forever Voyaging:

You play as PRISM, an artificially intelligent computer system which has mostly understood itself as a person named Perry Simm. You have been simulated in something approximating real time living in the small city of Rockvil. Now, a massive political and economic plan is being proposed, which is set to radically alter American life. Because you lived through all your formative moments, you have imaginative capabilities. You don't just calculate economic projections, you can gradually simulate further and further into the future, revealing what the long-term effects of the plan would be from a localized, human perspective. Most of the game is structured around you being freely able to move around the city and interact with things, with a wide range of freedom to record anything which seems to capture a sense of the state of society at that moment in time. It is a game about witnessing and cataloging all the little ways in which federal policies can play out on personal and communal scales.

As part of the conference proceedings, you can read my paper "From Wordsworth's Poetic Problem to Puzzleless Interactive Fiction." In short, Steve Meretzky's work here is foundational in the shift toward puzzleless interactive fiction, and is directly influential in particular to Chris Klimas' development of Twine, through which much current interactive writing (including the outline for the Black Mirror episode "Bandersnatch") is made. Meretzky, however, was in turn influenced by William Wordsworth, whose epic poem The Prelude provides the title, both for the work itself and the AI, PRISM:

The antechapel where the statue stood

Of Newton with his prism and silent face,

The marble index of a mind for ever

Voyaging through strange seas of Thought, alone. (III.60-3)

Wordsworth had his own parallel challenges to work through that prompted his developments in poetry. As I write in my abstract:

Wordsworth’s autobiographical epic poem The Prelude details the growth of his mind through formative moments. Understanding the development of his imagination in this way serves a crucial role in attempting to progress a larger poetic project concerned with the aftermath of the French Revolution. A Mind Forever Voyaging takes its title from Wordsworth’s Prelude, as well as parallels the general structure just described. In Meretzky’s work, you play as an artificial intelligence tasked with assessing the long-term ramifications of what is meant to approximate Ronald Reagan’s political and social policies. To this end, the artificial intelligence lived a full simulated life, to grow its own imagination through formative moments. This imaginative faculty enables a form of foresight into the localized reality of abstract political data.

You can read the full paper if you want to explore that connection in more depth, or go back and read William Wordsworth's The Prelude directly if you want to see how Wordsworth attempted to re-trace the growth of his imaginative power through what he calls "spots of time."

For more Wordsworth, you can also see "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" combined with texts from Eugenio Montale and Jorge Luis Borges in Daniele Giampà's generative poem "Tape Mark 3."

Around the Web

I just watched the film Waves, released in November 2019. Like Uncut Gems released in the following month, cell phone sounds feature as an unnerving interjection – an interruption into the silent sanctity of movie-watching most directly attacked through constant PSAs. What of telephones in literature?

- The Crossed Lines project is inviting contributions (due August 7) to an online exhibition of literary telephones. Don't have ideas for that? Save that page and check back later to see what they collect.

- For more inspiration, with substantial commentary, you can read Sophia Haigney's "An Elegy for the Landline in Literature" published in The New Yorker last week. (Thanks to Default Friend for bringing this to my attention this morning. It is handled via email rather than call-in, but you might enjoy her advice column.)

And what if all that reading about telephones does not quite satisfy your interest in intrusions?

- Mike Jay's "'The Fruitful Matrix of Ghosts': The Psychic Investigations of Samuel Taylor Coleridge" offers a lengthy account of Coleridge's opium visions and the poet's complicated struggle to account for them.

And for an intrusion into your week which is neither landline nor ghost, be sure to check in via Zoom this Saturday (August 8) at 2 PM EST / 7 PM BST for a discussion of poetry in the age of hyperconnectivity, with poet Charlotte Geater joining as guest. The link for that is going out to the email list, now and again this Friday (August 7) alongside my email lecture on "The Hyperconnected Lyric." Be sure to subscribe below if you have not, so you can keep up with these events, these monthly newsletters, and, currently, my weekly course on "Literature and Hyperconnectivity."