Universal Baseball's Faithful Crowds

PreCursor Monthly — November 2020

Fanaticism? No. Writing is exciting

and baseball is like writing.

You can never tell with either

how it will go

or what you will do

– Marianne Moore, from "Baseball and Writing"

We are mere ideas, hatched whole and hapless, here to enact old rituals of resistance and rot. And for whom, I ask, for whom?

– Robert Coover, The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop.

Amid all the absurdity of this year, the most striking for me has been seeing simulated sports crowds. Audiences took many forms: cardboard, virtual, robots, noise, and more.

The stands are filled with fake people. The air is hazy with wildfire smoke. Players are wearing medical grade masks. But America is playing baseball. pic.twitter.com/u6hq551FXQ

— James Hamblin (@jameshamblin) September 15, 2020

I’d like to nominate cardboard humans watching baseball in a dystopian hell scape for photo of the year, thanks. pic.twitter.com/DeQmFjuM45

— 🇨🇦 Marshall Ferguson 🏈 (@TSN_Marsh) September 10, 2020

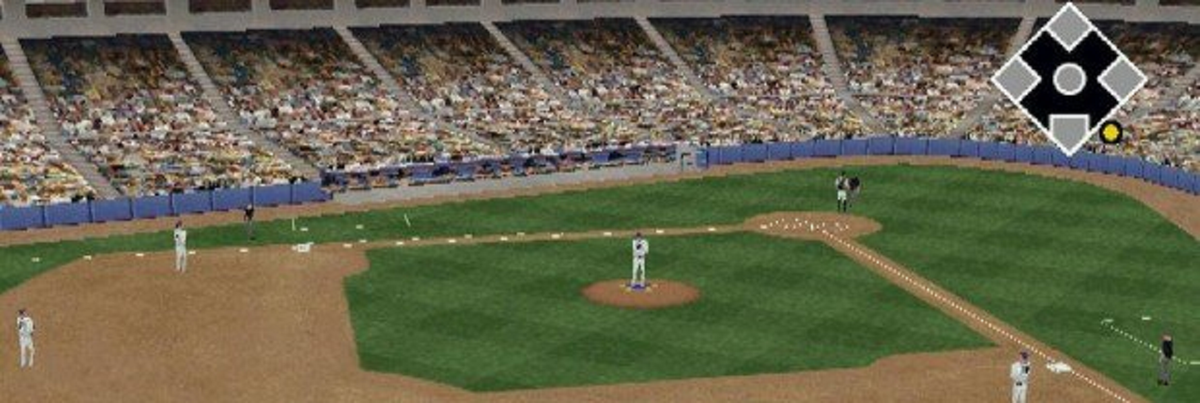

No fans? Not on FOX Sports.

— FOX Sports (@FOXSports) July 23, 2020

Thousands of virtual fans will attend FOX’s MLB games this Saturday. pic.twitter.com/z9oQU0rYuC

Oh no, it's going to be a modern reinterpretation.https://t.co/fMs5MWL1sC

— Timothy Wilcox (@PreCursorPoets) July 13, 2020

The Red Sox are experimenting with piped-in crowd noise at Fenway. Here’s how it sounds.https://t.co/fovfWYauj0 pic.twitter.com/lFiK9lZ9bV

— Boston.com (@BostonDotCom) July 10, 2020

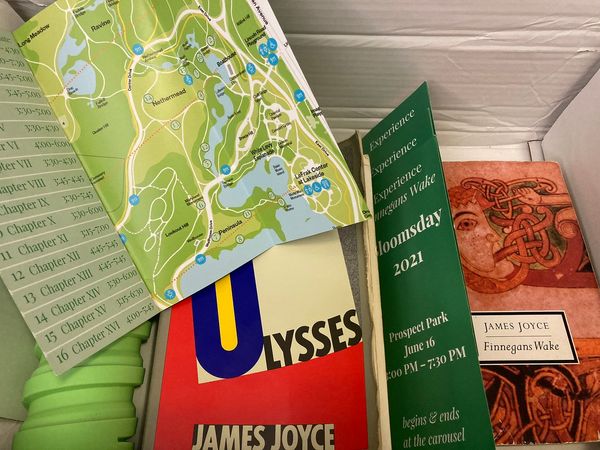

All of this reminded me primarily of Robert Coover's excellent novel The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop., but in typical PreCursor Poets fashion, we will be going on a literary voyage that brings online narratives and early computer programs into the conversation.

In mid-July, I asked, "How would you adapt a man's imagined singleplayer tabletop baseball game for film?" Of 28 votes, 32.1% favored "Low quality CGI audience," followed by 28.6% for "Audience sounds w/ empty [seats]." 25% thought that, for the sake of film, stylistically, it should be a full, real human audience, even if we are to understand that we are seeing into a man's imagination.

That's a small sample of views on a hypothetical film. How does literature do it?

Simulating Baseball

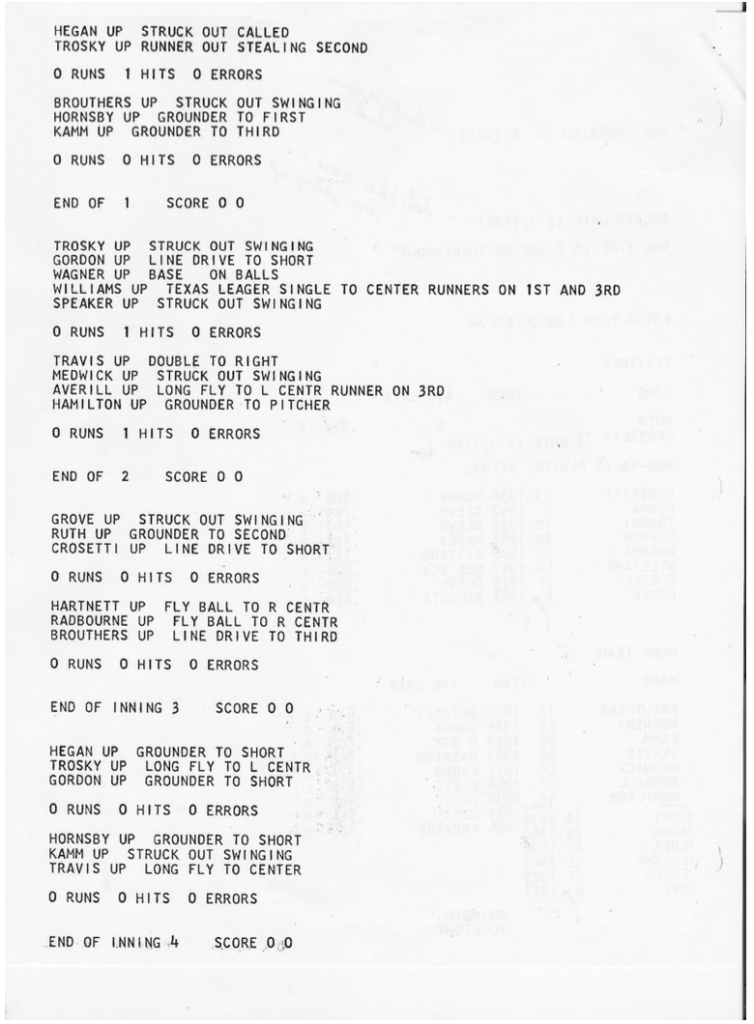

To start with some brief timeline: IBM developed BBC Vik: The Baseball Demonstrator in 1961.

The program simulated a baseball game. Though normal baseball is played by real people in 3D space with real-world physics and so on, the game has a series of rules which allow us to abstract it in this way. What we are concerned with are a series of events, which can be recorded numerically and brought into all sorts of statistics. In that way, IBM's computer could play baseball.

Outside of computers, wargames expanded their reach through the 1950s and 60s. The more widely commercial Dungeons & Dragons comes later, in 1974.

Rewind several years: Robert Coover's The Universal Baseball Association is published in 1968, in which a man plays baseball via a rule book, dice, and his imagination. The context of this novel precedes, then, the sort of commercial products we might imagine, but follows from a point where computers could already generate the core game. What the computer does not do, however, is emotionally invest in those numbers, the names, the history.

Lastly, looking ahead to the discussion of recently published electronic literature below, Coover was, notably, one of the founders of the Electronic Literature Organization in 1987.

Baseball as History

Even: that they close down the Association. Why not? Because what would all the past mean then without the present process? Nothing at all, but so what? No answer: only dread.

The Universal Baseball Association is a wild novel. It is bleak (detailing a man spiraling deeply into alcoholism), but also at times hilarious.

The game is entirely Henry's own invention, and he is its sole player. Its stakes are, realistically, zero, but a sense of sunk-cost makes those stakes seem increasingly great. Baseball, to Henry, stood out through "the beauty of the records system which found a place to keep forever each least action." As partly a religious story, the novel explores the way in which baseball gives life meaning. Every little thing is crucial to the whole of existence, the multi-generational lineages, the record-keepers, the fans.

At one point, Henry thinks, "ball stadiums and not European churches were the real American holy places." The context for this thought is the live audience at games: "There were things about the games I liked. The crowds, for example. I felt like I was part of something there, you know, like in church, except it was more real than any church."

For us now, a major controversy amid the pandemic has been the closure of or restrictions on religious services. As people are forced onto online services, this communal element is lost, as are surrounding gatherings, prayer groups, study groups, and many forms of service. In place of this, we fill our stadiums with cardboard cutouts. We sit at home and watch these fake people watching. We become J. Henry Waughs.

sure, there was a fence and a ball sailing over it, but Henry didn’t see them—oh, he heard the shouting of the faithful, yes, they stayed with it, they had to, but to him it was just a distant echo, static that let you know that it was still going on.

As the proprietor of The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., Henry is the sole audience of everything – from the mundane to the incredible statistical anomalies to the symbolic power of the newly legendary son of an earlier baseball legend taking the field amid the height of his career and the stadium's special day honoring his retired father who is watching on from the stands. An unlikely series of rolls means disaster: the son is struck and killed by the ball.

Now Henry is stuck. He has to play the game out with increasing frequency, find some sort of recompense, some meaning, some narrative closure. Depending how we interpret Justin Turner's post-World Series celebration, we may now be stuck, too.

Unchanging Channels

Don DeLillo put out a new novel, The Silence, on October 20. Electricity – and so also all digital technology, our communication systems, and television, right in the middle of the Super Bowl – suddenly cut out on a massive scale. One character begins to channel the language of the lost football broadcast (and commercial breaks). I wrote a spoiler-rich commentary: "Don DeLillo's Sublime Silence."

No End Zone for Sports Literature

Its title a clear play on 1776, the year of the United States of America's independence, 17776 is a work of electronic literature hosted on the sports news website SB Nation. Originally disguised as an article on "What Football Will Look Like in the Future," a normal-looking page which quickly gets taken over by a barrage of calendar images and overlaying text, the story was able to go viral – reaching millions of viewers.

The mass use of online communication shows a vast willingness to read and write text at length, and cases such as this show an interest in literary, formally inventive work, even if those people would not consciously think they would like to pick up DeLillo's The Silence.

The work takes a fictional look into the far-future as a 20th century space probe gets set up for quantum communication. Conversing with other probes and with humans on Earth, this inhuman perspective centers an introduction to a futuristic version of football. The games take place across vast distances (multiple states) and time (years), with thousands of ageless people moving or defending a football across America at once.

Where this gets especially interesting for us is that, though you have these space probes with comprehensive aerial views, the dynamics of the game do not always support visual media. In "Chapter 6: Page, Arizona," one probe comments about a particularly poorly designed game, "I wouldn't want to watch it, but I'd love to read about it. It's like baseball."

Granted immortality, humans play out their lives in endless sports rituals. It's entertainment. It's narrative. It's history. Even when things no longer quite function the same, there is continuity.

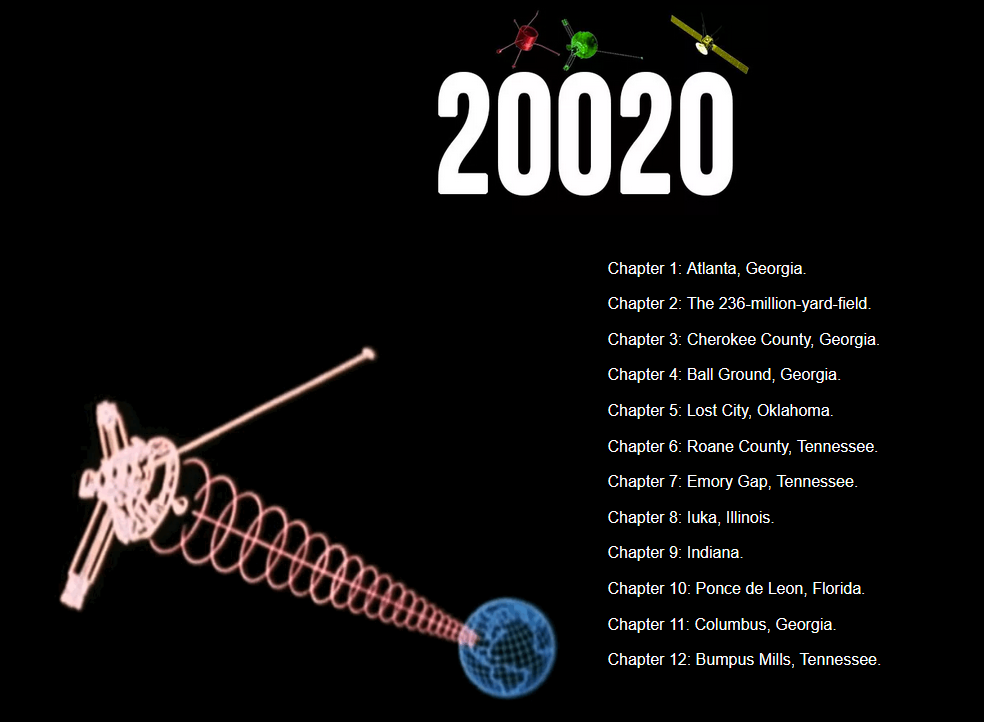

While we play this out with cardboard, images, robots, noise, literature brings us out of the spectacle and into the lives of those involved. 17776 came out in 2017, and its sequel, 20020, was just released through September and October of 2020, with 20021 planned for 2021.

It is a future of endless art and play – perhaps an existentially terrifying amount, but we are not ourselves there. For now, we are playing baseball for a simulation of the human voice echoing through our stadiums, because we need to keep that history going, keep up the records, the statistics.

As Marianne Moore writes in "Poetry," "all these phenomena are important." What we need, however, is not real gardens with imaginary toads, but "imaginary gardens with real toads in them." We are, then, interested in poetry.

Around the Web

- Want to read more electronic writing? Check out issue #5 of Taper, an online literary magazine of computational poetry.

- Want to prepare your own generative poem using a work from Taper #5? I wrote this simple step-by-step guide.

- Want to hear about negative capability from the British Romantic era to the Information Era? I was recently on James Simpkin's podcast, Primitive Accumulation: YouTube or Anchor (audio).

- Want to explore the work of William Blake in a new way? The Yale Digital Humanities Lab Team is launching BlakeTint, a new tool for "Quantizing Color in William Blake's Illuminated Books."

This post was sent out as my monthly newsletter for November 2020. Previous entries have included such topics as "Writing of/for the Future" or the Galatea myth from Ovid to neural nets. To get more explorations of new literature, classic literature, electronic literature, and more in conversation with each other, sent straight to your inbox, subscribe below: