Sadder and wiser, we rise the morrow morn

PreCursor Monthly — June 2020

I recently wrote about two novels from the Spring of 2019 both imagining a grand pause as the global Internet is wiped out. As I discuss there, it's fictional on the surface, true at the core. One year later and we're living what appears to be the opposite, but isn't really. Just as the loss of the Internet is used in these novels to give greater emphasis to what precisely is lost and what precisely these networks could be, the current pause of our "normal" reality has shown the value of physical presence, our relationship to space, and that where we excel is at the intersection of the physical and digital worlds.

Physical lockdowns and social distancing measures in many ways accelerate the encroachment of cyberspace over meatspace. In some economic contexts, this has been true. The pandemic has been a huge boon for companies such as Amazon and Zoom. At the same time, quarantine has revealed how unsatisfying this digital world can be. Five weeks ago, Drew Austen wrote about this for Real Life magazine:

Live events replicated via Zoom feel less like convenient alternatives than inferior and sometimes tedious simulacra. Instead of the full sensory immersion that we experience at a party, concert, or even a meeting, we have flat representations in browser tabs or apps, competing with the rest of the “content” delivered by the same screens.

There are many new possibilities offered by the Internet, but in trying to simulate the old, we simply lose the old with little recompense. Austen goes on to suggest, "if we hope to avoid settling for an atomized, decontextualized existence in which our primary identity is that of the consumer or user — one that isolates us and even pits us against one another — we will eventually have to find a safe way to return to public space." This fantasy that we could just pause and then eventually, when carefully evaluated, unpause has in recent days been shattered. Across the country, people have been returning to public space (including in COVID-19 hotspots) in massive numbers, but not in some hypothetical "safe way."

The reality, of course, is that life was not waiting for a formal national unpause. Things were still happening in the world, and following the May 25th killing of George Floyd, there was an unspoken consensus that wholly online political organizing didn't really work. People have taken to the streets, and at the same time taken the streets online. In a hypermedia spread – text reports, images, video, and livestreams on the ground, chatrooms and discussion forums giving ongoing commentary – the ongoing protests are a global media event. Physically, recent events have become impossible to ignore, while these ephemeral actions' archived digital shadows have become the foundation for wildly competing narratives.

The one thing that is universally clear is that wall-to-wall coverage of the fatal importance of social distancing has been replaced by the shoulder-to-shoulder movement of public masses and government figures alike. The latter is not just the police, but also prominent figures such as New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and presidential candidate Joe Biden, who both shared photos of themselves talking with strangers from distances of substantially less than six feet. At the same time, de Blasio has the city still under lockdown and Biden has made no announcement of an updated policy stance against lockdowns.

This is because both still believe the virus is a real threat, but circumstances have brought us to a point of failure in our imagination of our life in this increasingly digital era. As the need for public presence appears increasingly urgent, then surely it would not suffice for them to employ the "inferior and sometimes tedious simulacra" identified by Austen. Rather than take the past 10 weeks to radically rethink the integration of technology in our lives, officials such as de Blasio have let it suffice to prop up the fantasy of quarantine as a dam holding back the "normal" of face-to-face life. Once that barrier is gone, it's gone, and we're left with no framework for how to sustainably navigate our digital-era pandemic.

It is possible that an upcoming spike will prolong current lockdown efforts, but the current, sudden absence (in word and deed) of distancing reveals a substantial imaginative shift. For most people, this was less a conscious rebalancing of priorities and more a passive falling away. Becoming part of the image of the shoulder-to-shoulder crowd is familiar, and holds a powerful cultural resonance.

As I've been discussing in posts and videos, it is an observable trend in literature that writers avoid grappling with the digital era. It is much easier – in writing and reading – to return continually to what we already know. This is why so much literary fiction today is historical fiction, and that even within something like cyberpunk, there is so much reliance on not just the conventions but also images of genres such as detective fiction.

What I want to emphasize here is that these trends are not just about our literary imagination. What we can (or cannot) imagine for literature is not a meaningless, self-contained world. We struggle to write about this world because we struggle to imagine it in life. We live this digitized existence, but do not always perceive everything about it. It is thus not a matter of deciding to swarm public space or not. We do what we can imagine, and literature excels in providing a space to develop our imagination and to provide what William Gibson calls in "The Winter Market" a "vocabulary of feeling."

As promised, a selection of new literature, classic literature, and electronic literature to incorporate into your vocabulary of feelings:

New Literature: If you want to understand something, read a poem about it

I wrote recently about trends in fiction as seen in a selection of May 2020 novels and television. Within that context, I discuss two newly published pieces of short fiction by Nicole Zhu. I also wrote in more detail of Percival Everett's new novel Telephone. Perhaps most interesting right now, however, is Fran Lock's poem "in the presence of enemies" from the June 2020 issue of Poetry Magazine.

In Lock's poem, protest against police brutality and the surveilled, social world of Instagram are, as in life, in dialogue. Neither is subsumed into being a metaphor for the other; rather, a whole mess of specifics swirl together in a tower of language, angry and rapid-fire. More worthwhile than any other hot take or article, if you want to understand something, read a poem about it. More than even a livestream, imaginative engagement with texts such as Lock's brings us closer to our actual experience.

Just as the opening quote from 1832 serves Lock's present purpose, Lock's poem itself appears extremely timely, despite necessarily emerging out of an entirely separate event from at least last year. The eternal springing of hope is replaced in Lock's first line with the declaration that "hope springs ridiculous on instagram." Removed from Pope's leap of faith in the overall rightness of God's purpose, Lock instead justifies a sense of anger in face of the "sectarian and bestial" Internet and the injustices of the wider world. These two parts form "conjoined twins, / dressed in the lockjaw of identical violence."

Of the 33 poems in this issue of Poetry, Lock's poem was a rare example of one which consciously reflected on our current technological context. For others, see "My Phone Autocorrects 'Nigga' to 'Night'" by Karisma Price and "Text Message" by Anthony Anaxagorou.

Classic Literature: Too much news will itself demoralize the nation

John Berryman's "World-Telegram" is a 1939 poem about the overwhelming experience of just a quick glance at the titular newspaper. On just the cover, the speaker finds oddities, human tragedy, global political conflict with the potential for military conflict, a glimpse of hope, the threat of violence, and actualized violence. The inside is similar, covering everything from a feel-good story on "penguins" to the sadness of reading about "Four persons shot."

Most of the poem follows passively in relaying the contents of the newspaper. Like in actually viewing the newspaper oneself, this comes together in a succession of images. We do not, after all, experience the newspaper all at once, but dart our attention around to different columns, different stories, different photographs. These earlier stanzas have occasional subjective interjections, but it is not until the final stanza that the speaker gives a sustained comment on the experience of reading the newspaper:

News of one day, one afternoon, one time.

If it were possible to take these things

Quite seriously, I believe they might

Curry disorders in the strongest brain,

Immobilize the most resilient will,

Stop trains, break up the city's food supply,

And perfectly demoralize the nation.

The quantity of the news, relayed to us over 33 lines, is ultimately just the news of one afternoon. It would be one thing to go through all this in periodically catching up, but the New York World-Telegram is a daily newspaper. This quantity repeats itself day-after-day. Taking this all seriously would, Berryman's speaker suggests, cause "disorders" in the brain on an individual level which would then extend to eventually the demoralization of the entire nation.

What is especially interesting in revisiting this poem now is how our access to news has only gotten more frequent and more global, and harder to get away from. It is no longer a newspaper as a distinct object one has to pick up, but instead devices which one uses for various professional and social needs are continually barraged with news. We might further think again of the role of Instagram in Lock's poem above.

I recently thought of "World-Telegram" in context of a viral story involving an exchange between two individuals resulting in one being fired from her job and losing her dog. Having encountered the story, I of course had opinions about the exchange, but another question entirely is what effect does it have to be regularly made aware of and tasked with contemplating arbitrary – what is recorded? what is fit to go viral? – events between random strangers. It is perhaps worth considering how useful it is that online action can quickly get a private citizen fired, and yet when someone actually dies amid state violence, people instead take to the streets in the tens of thousands. Is it not then a fantasy that online mobs are justified by an ability to hold people accountable, and so we must continually enact this ritual against people at all levels of power?

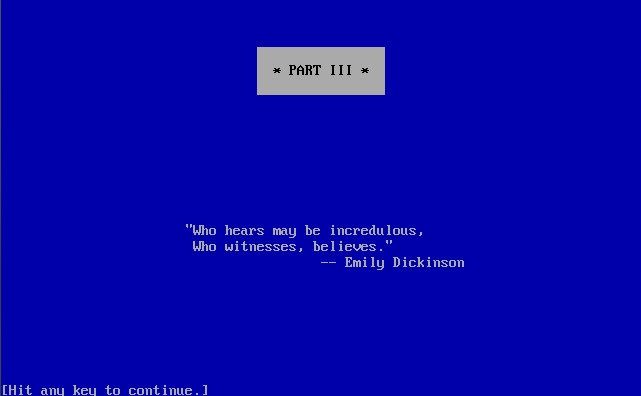

Electronic Literature: Who witnesses, believes

I will have much more substantial comments coming soon, but in the above context, I must recommend the 1985 interactive fiction work A Mind Forever Voyaging. If you looked at early speculation around Cyberpunk 2077 and wanted to play as a media, A Mind Forever Voyaging is the game for you.

You play as PRISM, an artificially intelligent computer system which has mostly understood itself as a person named Perry Simm. You have been simulated in something approximating real time living in the small city of Rockvil. Now, a massive political and economic plan is being proposed, which is set to radically alter American life. Because you lived through all your formative moments, you have imaginative capabilities. You don't just calculate economic projections, you can gradually simulate further and further into the future, revealing what the long-term effects of the plan would be from a localized, human perspective. Most of the game is structured around you being freely able to move around the city and interact with things, with a wide range of freedom to record anything which seems to capture a sense of the state of society at that moment in time. It is a game about witnessing and cataloging all the little ways in which federal policies can play out on personal and communal scales.

Literary Study: Poetry, poetry every where

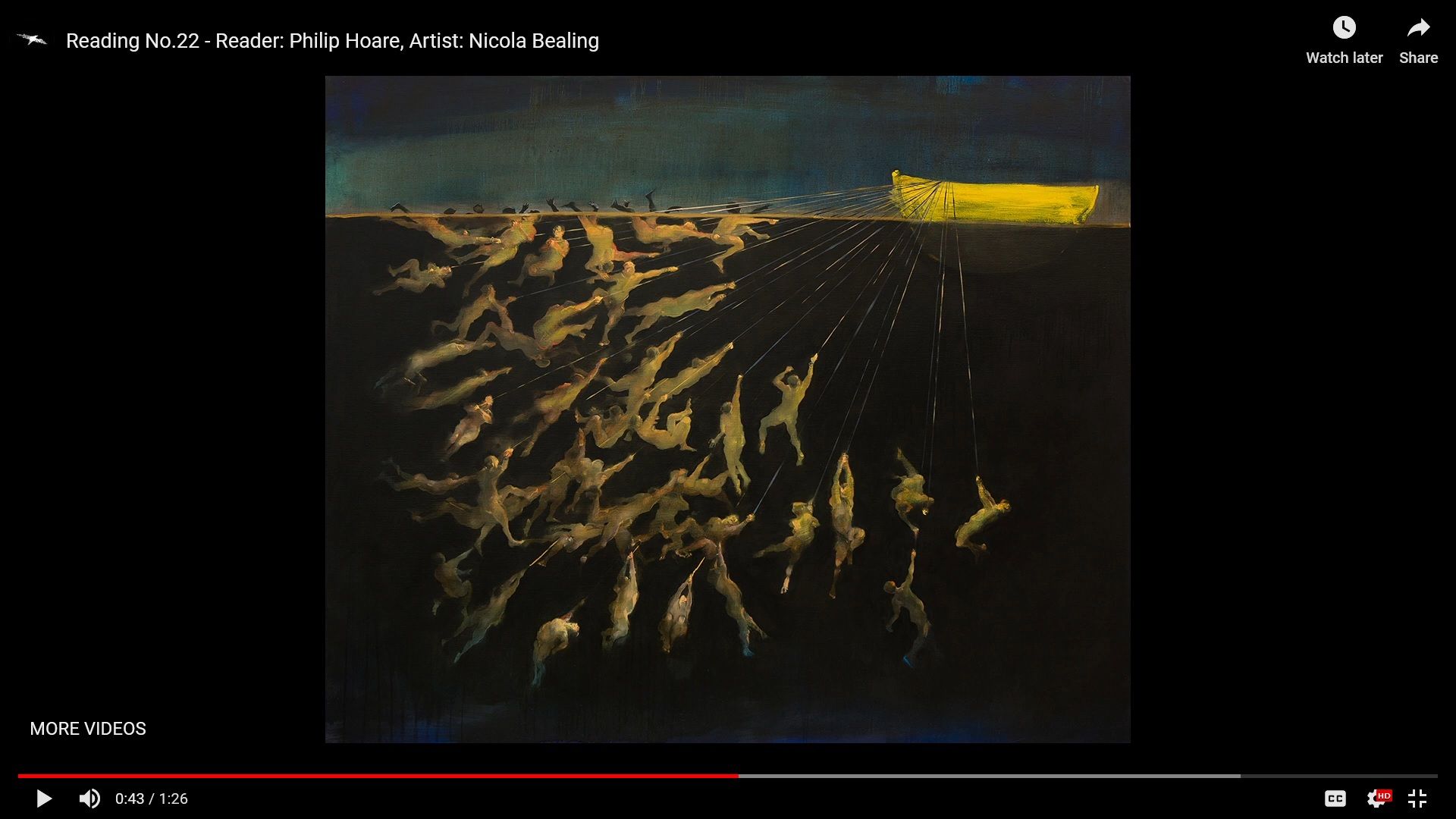

Recently completed in 40 parts, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Big Read is an online celebration of the British Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge's famous poem "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner." If you have ever heard of an albatross around one's neck, this is referencing (intentionally or not) Coleridge's depiction of a mariner who shoots down an albatross and is then forced to wear it around his neck as he is cursed first through a series of horrors on his ship and then to wander around sharing his story.

Like the mariner, a series of 40 readers – spanning writers such as Jeanette Winterson and actors such as Willem Dafoe – have been compelled to speak this tale. These audio recordings are combined with visuals from a series of 40 artists. Collected through the University of Plymouth, the project features no direct commentary on the poem, but through the range of different approaches to reading and attempts to give visuals to the poem, we are ultimately faced with a large selection of different interpretations and mash-ups.

Writing for The Atlantic, James Parker explains how "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" was "Made for 2020." He writes of the underlying poem, "To us, today, it speaks of the sea-moment, the liminal state: the treacherous zone between a ruined world and a new one." That the poem should have such a flexible impression is not incidental.

The work comes from Lyrical Ballads, a book written together with fellow poet William Wordsworth. In the original 1798 edition, Coleridge's poem started the collection. As Coleridge describes the division of labor for Lyrical Ballads in his Biographia Literaria, Wordsworth's task was to impart a supernatural feeling into everyday events, while Coleridge was to write about characters who were themselves supernatural "so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith." Even if you have never heard of albatrosses around one's neck, you have certainly of the "willing suspension of disbelief." In the case of "Rime," we are able to suspend our disbelief and accept this figure of the cursed mariner because Coleridge adds that "human interest" and "semblance of truth." Whether on a personal level, an ecological level, or reading the poem against a much more specific moment, we understand something of the mariner even if we struggle to truly grasp everything happening around him. That is why the peculiar image of the mariner's guilty burden is able to function as a somewhat common phrase.

As Parker mentions in The Atlantic, this Big Reads project was "three years in the making." It just so happens that we only get the completed version, released on a daily schedule from mid-April to late May. A daily schedule of sub-two minute videos, featuring dramatic readings and original art, makes for an engaging form fit for easy consumption online. It is in that way competing against the daily feed of other news, some of which may overwhelm us. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Big Read didn't win out by the numbers, but perhaps we'd all be better off if it had.

I hope that this literary overview has directed you to valuable material to think about or think with as you start this new month. Let me know your thoughts.

This post was distributed – along with a curated selection of links to recent, interesting work by others from around the web – as my inaugural monthly newsletter. If you want to see more content like this each month, subscribe below. Sign up now and I will also be sending out an invite to a free mini-course delivered via email soon: