The Origin of All Poems

A novel was the first example I was given, in the course of my schooling, of a large-scale project.

Obviously work done in other fields – the efforts of science, the laborious research of historians, and the great achievements in history itself – is complex, but this was not strongly impressed upon me in high school. Most work at this level takes one of two forms:

- Knowledge-building (measured in multiple choice questions, checked by a machine)

- Problem-solving (with work shown, but dealing primarily with short, exemplary problems)

In the case of the novel, I was given the full, completed work of years of effort from an expert; I read every word; we paused and studied word choice, structural design, application of figurative tools, etc.; and, in some cases, we learned about the author and background details that went into composition.

Assessment might still be simple here (What does Gwendolyn Brooks use between the lines of her poem "We Real Cool"? A. Simile B. Sonnet C. Enjambment D. All of the above.), but some version of the project is all there. At a higher level of study, I found out about manuscripts, editorial history, editors, etc. – but realizing the basic structural work that goes into crafting a great novel was by far the most astounding accomplishment I had learned about.

It was a few years before I realized that level of planning and effort could be applied toward other ends as well – at which point I read about every single major my college offered – but literary work remains a distinct sort of project, which gets us into questions of aesthetics.

Literature as Project

If you are interested in frameworks through which to understand society, you likely come into frequent contact with the ideas of Michel Foucault. He wrote extensively about topics such as surveillance, power, identity formation, and sexuality as they developed in history and as we now inherit them and employ them. The political management of COVID-19 is an extensive example of what Foucault identified as "biopolitics," in which the state manages biological life.

As people are reading and writing more than ever, Foucault's 1969 lecture "What Is an Author?" is also increasingly relevant. The speech came two years after an essay by another French theorist, Roland Barthes, declared "The Death of the Author."

Many people really hate Barthes' theory – that we must ignore notions of "authorial intention" and biographical context to open up a richer world of meaning in texts, that "the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author." Some authors especially insist that, actually, they very much do intend particular meanings, and that interpreting those is more valuable than finding some unintended meaning.

I think the insistence on authorial intention falls short in at least three major ways:

- Even the best writers, writing at all extensively, will miss some implications of certain words, or vast webs of combinations of words. This creates a gap between what is intended and what is on the page. Readings around this sort of gap can fall into bad faith – especially when you move away from Barthes' point and try to ascribe those meanings to the author – but in addition to linguistic trickiness, psychology offers us a whole history of how we possess more images than we understand.

- If interpretation is being assessed in terms of things said or written outside of the work itself, that material is inevitably categorically different from the work. If everything in your poem can be clearly presented in an accompanying essay such that nothing is left unaccounted for, it is probably not a very good poem since there is no necessity to its form.

- If interpretation is being assessed in terms of things said or written outside of the work itself, that material is inevitably temporally removed from the work. The most popularly derided example of this is J. K. Rowling's periodic revisionism of her Harry Potter novels, but anyone speaking about past work on a novel – anyone who continues to think in any substantive way – will add, subtract, adjust according to present thinking, which is further altered in reaction to external interpretation.

But somebody's doing the writing. That someone is what we call an "author," but Foucault backs up to explore the function the word serves that makes it useful to us. As he explains, before the 17th or 18th century, scientific writing relied on the name of a respectable author, while literary writing could be accepted with no concern for the identity of the author. There was a reversal, and anonymous and communal texts made way for attention to literary geniuses.

Foucault explains the idea of the "author function" as rooted in discourses. In particular, the name of an author is useful as a classification system for someone who has written multiple texts. It does not necessarily matter who wrote one text, but when that person wrote several, the author's name connects that work together.

Where I find Foucault's distinction here useful is that while adhering strictly to authorial intention within a single work offers limited insight which is far from exhausting the value of the work, looking at multiple works can reveal an ongoing intentional trajectory – or project.

Thus, we have the work of literary art as a foundational example of an ambitious project, but this interest can be expanded further to consider the ideal or subject pool or perceptive mode (etc.) toward which one given work is just one attempt – even if you might see one work in particular as a crowning achievement. The "author function," it seems to me, is not just a useful category for readers, but describes the way in which an author's creative efforts extend beyond any given page or book.

Foucault ultimately suggests moving away from interest in the author – returning to tradition of anonymous literature – so that we might ask instead questions such as "Where has [this discourse] been used, how can it circulate, and who can appropriate it for himself?" Understanding the discourse, however, requires not the author, but the author function.

Celebrating Myself, Transforming You

Walt Whitman's major poetic project is Leaves of Grass, a collection of poems first self-published in 1855, then continually expanded, revised, and reorganized with editions in 1856, 1860, 1867, 1871, 1881, and 1892. He was striving toward something and took its production – and some initial reviewing of the book – into his own hands, and he kept at it in new and changing forms; he also won, and has been extraordinarily influential on poetry since.

As discussed in April, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote in 1821 that "poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world." Whitman presented a similar sentiment in 1855:

Of all nations the United States with veins full of poetical stuff most need poets and will doubtless have the greatest and use them the greatest. Their Presidents shall not be their common referee so much as their poets shall. Of all mankind the great poet is the equable man. Not in him but off from him things are grotesque or eccentric or fail of their sanity.

He wrote this in a double-column essay placed at the front of his self-published first edition of Leaves of Grass. Repeating Shelley's sense of the great poet's fundamental insight, Whitman goes on to explain,

The greatest poet does not moralize or make applications of morals . . . he knows the soul.

As we get into the poems themselves, Whitman again makes promises, grounded in a sense of a shared spirit. He begins his opening poem, which he later titles "Song of Myself":

I celebrate myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

Published on the 4th of July, Whitman celebrates not the holiday's usual terms, but himself – but with promise that something there is shared between you and him. Progressing down 20 lines, he works to unseat the confidence of the reader – some typical buyer of poetry – in his formal learning:

Have you reckoned a thousand acres much? Have you reckoned the earth much?

Have you practiced so long to learn to read?

Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?

Then, from that basis, he makes this core promise:

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun . . . . there are millions of suns left,

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand . . . . nor look through the eyes of the dead . . . . nor feed on the spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from yourself.

No longer bound to critical understanding, or to what is recorded in books (even this one now in-hand), you will "possess the origin of all poems." This is distinct from the sort of "meaning" you might get at from applying your reading skills; the "origin" will make you, too, a knower of the soul.

What the poem does not leave you a knower of, however, is Walt Whitman. In the end, we are left with this:

You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,

And filter and fibre your blood.

Failing to fetch me me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop some where waiting for you

Whitman presents a poetic bait-and-switch. He asks us to stop this day and night with him, with this "Song of Myself," but at the end of this night, he has departed "as air." Seeking toward that ideal, though, he suggests was "good health."

Perhaps the real American, the real poem was the listening we did along the way. Returning to Foucault's question of "how can it circulate," this has proven the abiding legacy of Whitman since: Providing a manner of speaking in poetry picked up by generations of Americans hence. Missing Whitman in one place, poets continue to search another; he waits.

Foucault proposes the question, "Who can assume these various subject functions?" and Whitman answers him from the past, "what I assume you shall assume."

Container of Multitudes

One of Whitman's most famous passages concerns his idiosyncrasy, part of why the reader keeps missing him:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then . . . . I contradict myself;

I am large . . . . I contain multitudes.

There was a growing sense picked up in literature that, as more and more of the world became precisely, scientifically "known," that actually this would not be feasible for people (and probably many other things). A complex instance of this is in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

Both physically created in a lab and taught by a concise list of texts representing a Romantic-era English education, the novel's unnamed creature insists he is not an automaton, but a deeply feeling individual. His body is composed of actual multitudes, and following both Mary Shelley's model and critical attention to the novel in the late 20th century, Shelley Jackson picks up the image of the Frankensteinian monster in her 1995 hypertext novel, Patchwork Girl.

In Patchwork Girl, Jackson imagines Mary Shelley herself reconstructing the female creature destroyed in the narrative, with Jackson blurring the line between piecing together a body and piecing together a (non-linear) text. Jackson continues her Frankensteinian hypertext work with my body – a Wunderkammer in 1997 and The Doll Games in 2001, but she also pursues wider projects around body forms and writing in patches in other literary mediums. As I wrote about in December, her Instagram story, Snow, progresses one word at a time each day there is snow near her.

Writing as the female monster in Patchwork Girl, Jackson presents the patchwork style as itself infectious, an aggressive act by which the monster seeks to win:

The flow, which turns out to be the main point. Not the passages I am moving through, however beguiling … but the sheer pleasure of movement

And elsewhere:

if you think you’re going to follow me, you’ll have to learn to move the way I do, think the way I think … when you are thinking my thoughts, my battle is almost won, because you’ll begin having trouble telling me apart from yourself … and when you see me, you’ll wonder if I’m chasing you

The flow across passages is noted to be "the main point," above the content of the passages themselves. The images of chasing reflect Victor Frankenstein's mad chase of his creation across the vast sea of ice, but there is literary chasing as well as physical going on in Frankenstein, which Jackson picks up on.

When Victor expresses anguish over the idea that he has strayed too far from reason and caused the death of those he loved, he is immersed in the rhetoric of Paradise Lost and The Sorrows of Young Werther, which he gained from the creature who has been using those as some of his primary modes of reference for the world. Jackson's monster suggests that the reader of Patchwork Girl will likewise inherit a new mode of thinking from this patchwork text.

In particular, it is specifically if you want to pursue this creature and understand her that you must learn to navigate this new literary form, and then you have that possibility of thinking and speaking forever. This is precisely how Whitman structures the lessons of Leaves of Grass – which is to say this is the origin of all poems: Authors inherit modes of expression, and then pursue their own project on top of that, expanding the range of expression which then infects others.

Whitman says, "Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems," and it is very much a possession. You possess it, while it possesses you.

Possession

A different sort of possession is the guiding interest in non-fungible tokens (NFTs), a method of representing and proving ownership of digital media. The file may circulate, but only one person owns the associated token.

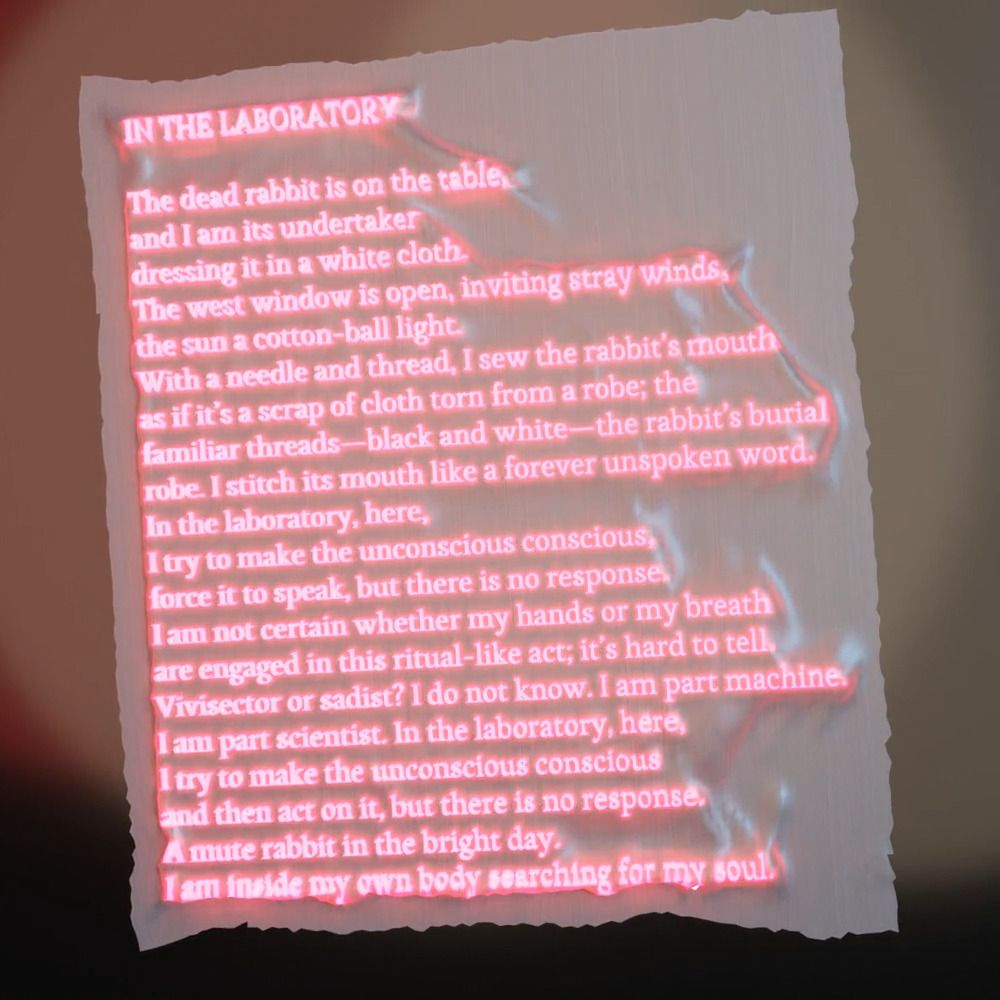

James Yu is one of a growing number of artists selling poems in this way. Sold on condition of proceeds going to Room to Read, a children's literacy charity, just one poem, "In the Laboratory," for example, sold for 0.3279 ETH ($754.70 USD). The interesting thing about the poem, though, is that it was not written by Yu.

Yu works with the deep learning language model GPT-3, which also powers his collaborative writing platform Sudowrite. He notes in the description for "In the Laboratory":

Each piece contains a poem

created entirely by GPT-3

with complete freedom to choose a

subject matter / title / body.

Humans acted as a sieve

selecting the best

but never editing.

The mechanics of a poem being "created entirely by GPT-3" go back to the model's training. Like the creature in Frankenstein, GPT-3 has been fed on classic texts, parses out recurring structures in poems (formal, semantic, stylistic), and generates new text within those structures. Currently, most poems coming out of this will not be very good, which is why humans need to act "as a sieve."

In a recent test Yu ran to see how well people could guess which poems were published by humans in small journals and which were GPT-3, I scored the highest of all participants through tracing out recurring faults in the model's understanding of poetry, but GPT-3 is certainly pumping out poetry which could be mistaken for the work of a still-learning student. Importantly, language models will improve over the coming decades – but the model will still not be an author.

GPT-3 can, with endless time and computational power, generate an infinite number of passable poems. It is very far, however, from being able to pursue an overarching project across those poems, the way Whitman did in writing and refining Leaves of Grass. GPT-3 cannot take on an author function.

All this can be taught through literature. It's all there for whoever is willing to stop a day and night in pursuit of the origin of all poems. This is an exciting time for the medium, with much more to come, but William Gibson's saying continues to be relevant:

The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.

And so while billions of people read and write on computational devices regularly, most people still have no idea what that could possibly mean.

do I abide? very well then, I abide

— 🎀 sonya semantically 🤖 (@sonyasupposedly) July 1, 2021

This post was originally sent out as my monthly newsletter. To get insights like this into literature (old and new, print and digital) each month, subscribe below: